The war admirably lends itself both to separate tabletop battles and to lengthier campaigns. The strategy, tactics, and weaponry of specific campaigns and battles form a practical basis for the off table planning that is an integral part of a wargames campaign. Highly suitable for adaptation as a map / wargames campaign, the movements of the opposing armies in 1356 that led to the confrontation on the field of Poitiers forms an intriguing prologue to the battle itself, presenting a marked series of objectives, any or all of which can provide the reason for a campaign:

- 1. The Black Prince is endeavoring to bring to battle King John's army before it is strengthened by reinforcing units crossing the River Loire on a front of 120 miles.

2. The French king, whose force without reinforcements is larger and probably stronger than that of the English, is trying to force battle upon the Black Prince before they are joined by Lancaster and his army who are endeavoring to force the passage of the Loire.

3. Lancaster need not actively enter the campaign, being used as a threatin-being to influence French movements who, in their turn and according to the terms of the campaign, may or may not be aware of Lancaster's presence.

4. Lancaster could so maneuver as to prevent French reinforcements reaching the King; or, he and the Black Prince could unite, when King John instead of the Black Prince would become the quarry.

5. If, all other things being equal, the French army concentrates as it did in 1356, then the Black Prince has three alternatives:

a. He evades them and resumes his march to Bordeaux - unlikely unless he abandons his slow-moving wagon train and his booty.

b. The Black Prince is brought to bay in a position other than the real-life field of Poitiers that might be disadvantageous to his numerically inferior force, although there may well be other defensive positions in the area that will not escape the English Prince's eye.

c. As in real-life, the Black Prince and his army accept the battle against the far stronger forces of the French king on the actual field of Poitiers.

Practical Aspects

Practical Aspects

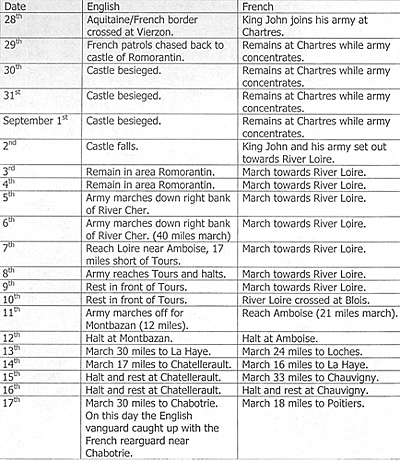

Large-scale maps of the area are required -- Michelin Carte A 1:200,000 Nos. 68 and 72, plus war diaries for both French and British (and one for Lancaster if taking an active part in the campaign). A wargames war diary consists of a sheet of paper with a left hand margin for the date, against which the events of each day are recorded. In this campaign the war diaries of both English and French will resemble, in greater detail, this march table.

War diaries are essential means of maintaining coordination between the movements of rival armies.

Movement on maps in a wargames campaign and the compilation of war diaries can be relatively complicated - its many aspects are covered in the book, Wargames Campaigns by Donald Featherstone (Stanley Paul London, 1970).

Rates of movement must allow forces to either move in a body (probably at the speed of the slowest factor) or else separately, mounted figures moving the greater distance, infantry next, and wagons last of all. As in real-life, forces march more quickly under stress and have to rest because of sheer fatigue, so a force will march not more than 60 map miles every four days. Note the distances marched, encouraged by pursuit, by the English on their way to Crecy and Agincourt.

A simple practical method of map moving is for the opposing commanders to each have a sheet of transparent plastic large enough to cover the area of operations on the map. To use, the plastic is placed on the map, its corners "keyed in" so that it can be accurately replaced if a single map is being shared. With a chinagraph pencil, mark in each day's march, moving on the map at scaled rates, i.e., on the suggested Michelin maps, where 1cm = 2kms, a day's march of 15 miles will be approximately 12cms, allowing for winding roads, etc. When it is thought that the opposing armies are near each other, BOTH plastic sheets are simultaneously placed over the map (by a third person or an umpire) until contact is made. Then terrain, bearing features of the relevant map area, is laid out on the table and the battle can begin.

It might be that part of one army has straggled and is a day's march behind their main body, the time of their delayed arrival will be noted in the war diary so that they will not come on to the wargames table until late in the battle.

Returning to the Poitiers campaign, a form of this delayed arrival is simulated by initially allowing a French force of 10,000 men (about the number in the actual battle). There are another 10,000 on the other side of the Loire, moving over a frontage of 120 miles to join the King. If it is assumed that they are in ten separate columns, each 1,000 strong, the campaign may be enlivened by perhaps only two or three of these reinforcing groups joining the King. Thus, if the campaign concludes as in real-life with a large battle, then the French force have realistically failed to mass their full resources.

Easier to cut the teeth on is another basic fictional campaign / game where the French need to make contact if they are to win, and the English have to hold them off or be destroyed.

In a wargame permitting considerable tactical maneuvering, the small British force under Henry V are moving across country in an effort to get across the River Somme before being cut off by the much larger French pursuing force. At the mouth of the Somme lays the English fleet waiting, in Dunkirk-like manner, to pick up and carry to safety the English army that has been wending its ravaging way across France.

The map is drawn so that the English, in spite of their faster rates of movement, are hard pressed to reach the safety of their boats without turning and giving battle to the pursuing French. The French do not have to attack the English, but if they do not bring them to bay, then the smaller English force will get away so it is definitely in the French interest to force a battle. Anyway, if they don't then there will not be a campaign! Certain points on the map provide very advantageous defensive positions for the English to make a stand. To give battle in the open, particularly on the extensive plain that stretches inland from the port, is to invite disaster because of the large numbers of mounted knights and men-at-arms who form a great percentage of the French force.

At the bottom right hand corner of the map, the two river mouths are marked A and B. At low tide it is possible to ford both these points. It has to be decided (and shown on the war diary) the state of the tides so that a force may either cross at once or be delayed. An ideal example of such an occurrence was the English crossing of the ford at Blanchetaque during the journey to Crecy in 1346.

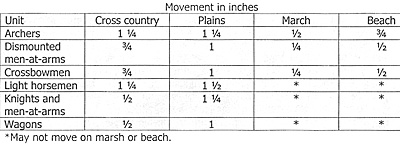

The rates of movement on the map are given at right and it is suggested that these move distances are scaled to use on the wargames table, so that dismounted men-at-arms for example will move across the plain at the rate of 1 inch per map move or 12 inches on the wargames table.

The rates of movement on the map are given at right and it is suggested that these move distances are scaled to use on the wargames table, so that dismounted men-at-arms for example will move across the plain at the rate of 1 inch per map move or 12 inches on the wargames table.

At bridges, fords, forest defiles, and mountainous tracks, it is considered that there will be an inevitable 'piling up' of the columns so that speed is cut by a half at these points.

The French have a train of wagons carrying their food - under no circumstances will these wagons be abandoned. On the other hand, the English force is living off the land and the few wagons they possess will carry food when available and the armor of their knights or men-at-arms. These wagons may be jettisoned if required, in which case the knights and men-at-arms will be required to march in their armor, which will cause the wearers to move at half their normal speed. To secure their food, the English must loot the villages and towns they encounter on their route. This means that either the food from the villages has to be brought back to the main body of the army in wagons, or else the main body has to go to the food. The method of simulating these factors are as follows:

- A village equals 1 unit of food and a town equals 3 units of food.

- One unit of food keeps the English army moving at normal speed for one day or at half speed for two days.

- To loot a town it is necessary for an English force to be 100 points strong whilst to loot a village requires a force of 50 points strength. These points values are made up by counting mounted knights and men-at-arms as 3 points. Dismounted men-at-arms (with shields) count 2 points. Dismounted men-at-arms without shields count 1 1/2 points. Archers and crossbowmen equal 1 point each.

If a town or village has been reinforced by French troops moving ahead of their main body, then it might be necessary for a small battle to be fought. In this case the inhabitants of the towns and villages will probably take a hand in repelling the English invaders. For this purpose it can be assumed that each town has 60 inhabitants whilst each village has 20 people living within it. These villagers are peasants of the lowest order, lacking adequate weapons and likely to be in awe of organized soldiery. So they must have a lower point value and a much lower morale rating than the soldiers with whom they might be allied or against whom they might fight.

It is possible that any wargame resulting from such an encounter would be a small affair unlikely to justify setting up a fairly involved terrain or allowing such an encounter to take up valuable wargaming time. It can be settled on paper by the following method:

- French and British soldiers will be counted in points as already nominated whilst the villagers count 1/4 point each.

- When the defenders are half the strength of the attackers (in points) then there will be a delay of one move.

- When the defenders are three-quarters strength of the attackers (in points) there will be a delay of two moves.

- When the defenders are equal in strength to the attackers (in points) there will be a delay of three moves.

- When the defenders are 25% stronger in points that the attackers then the latter will not attack the town or village.

Once a town or village has been taken, each attacker can bring away enough food for himself and two others. If wagons are taken along and enter the town or village, then three wagons can carry away enough food for the entire English army.

The towns and small castles dotted about the map ach have garrisons of 20 men-at-arms. They must be mounted if they sally out to attack the English, who have no means of besieging the towns and castles. It amounts to a situation where the English will not interfere with the garrisons providing the garrisons do not interfere with them.

At the beginning of the campaign, French light horsemen or foot in any desired numbers up to 50% of the entire French strength may begin the game on the opposite side of the river in an attempt to head off the English. They may bar the fords by planting stakes, which will take them 3 moves to plant. It will take the British 2 moves to remove and clear the passage through the ford.

100 Years War Campaign

Related

100 Years War Campaign by Don Featherstone

- The Bowmen of England Tactics of Military Efficiency

Battlefields of the Hundred Years War Visiting Yesterday

Reconstructing Agincourt A Wargame

Back to MWAN # 126 Table of Contents

Back to MWAN List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 Hal Thinglum

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com