So it does look like the results of this battle verifies that three weaker ships can pull down a pocket battleship. But that conclusion is based on action some days after the engagement. When the Graf Spee was scuttled, there was little doubt who won. But what if Langsdorff had decided to break out? He would have faced a force of three cruisers. The Cumberland had 8-inch guns. The other two had 6-inch guns, were also a bit damaged and they too were low on ammunition. Who can tell how that engagement would have turned out? Remember Langsdorff and the German headquarters believed that there was an aircraft carrier and a battleship waiting nearby. They believed the false report planted by British intelligence. It looks as if that false report is what sealed the victory for the British. The Fletcher Pratt Naval Wargame Rules do not have provision for intelligence as a factor in naval battles.

There was another key decision not covered by the rules. After about two hours of fighting, Langsdorff headed for a neutral port. Why? His ship was still able to make good speed, about 24 knots. He was able to use his guns effectively. He had pounded the Exeter until it was on fire, on water, and only able to fire one gun. He had taken out two turrets on the Ajax. At that point the battle looks like about a draw.

News reports filed after the battle but before the scuttle are interesting. They got some details wrong, but each side claimed victory. The German propaganda reports, "This German naval victory. . ." The United Press says, "The British men-o-war were victorious. . . ." What if the Graf Spee had stayed and slugged it out to the finish? How many of those cruisers would have survived? Hitler's verdict on the decision to break off the fight was harsh, "He should have sunk the Exeter." Admiral Raeder commanding the German navy signalled, "agreed" when Langsdorff radioed him that he was heading toward a neutral port. It was clearly a judgment call and Langsdorff made the decision. Again Pratt's rules don't provide for morale or whatever it was that shaped that decision. Langsdorff had been at sea under great stress, he was tired, and he had been knocked unconscious. In that state he had to make the life or death decision. The tradition in the German navy did not endorse the ideas of going down guns blazing.

At this point members of SWA get feel pretty smug. After all the pages of Lone Warrior are full of ways to inject fatigue, confusion, supply, temperament, faulty intelligence, and morale in battles. It looks to me as if these two decisions were more influenced by these factors than by objective facts. Just compare the risks that Commodore Harwood took with his force. Remember, at the start of the battle the experts knew Harwood could not win. This battle was won by the commander who was willing to dare more. That's hard to write into a set of rules.

However, Pratt's rules are excellent on firing guns and torpedoes. Each ship in the game was run by one player. When firing guns the player pointed arrows at the target and wrote an estimate of the range in inches. The shots were strung out in a salvo about one inch apart. Each shot fired was marked by a splash-mark where it fell. These could be golf tees, poker chips, or coins placed on the playing surface by the umpires. The firing player could then adjust the range in his next salvo. This was a simplified version of what gunnery officers did in the 1930s. This was before radar and laser range finders.

The Mark I Eyeball was used aided by optical instruments. If the salvo missed, the range was adjusted to reflect what the shell splashes indicated. Spotting the splashes was critical as was seeing the enemy. A ship could hide behind a smoke screen. Favorable light was important. A ship silhouetted against a sunset was at a disadvantage. Night firing depended on searchlights. Aircraft were helpful as spotters to report on where the splash marks were in relation to the target.

The target ship could do several things to confuse the gunners. Following a zig-zag course made range estimation difficult. Even better, a ship could chase the salvos, that is change course to head toward the splash marks of the shells that missed. This would make the correction by the gunnery officer too big. One report says the British actually faked splash marks by detonating depth charges near the surface. Maybe, but why reveal this during the war? Both sides in this battle made smoke.

The Graf Spee is reported to have used smoke floats as part of her smoke screen. All of these tactics are allowed for in Pratt's rules, and they produce results. Smoke was symbolized by screens of cardboard, placed on the playing surface. Night actions were fought in the dark using flashlights. Naval reserve officers assured Pratt that his rules rewarded tactics they used.

Torpedoes were another area where Pratt's rules were realistic. Torpedoes in 1939 ran near the surface leaving a trail of bubbles. An alert lookout could spot them, and a ship could turn to avoid them. Both sides in the battle launched torpedoes and in all cases they were spotted and evaded. This helps account for some of the turning during the battle. Pratt's rules called for torpedo tracks to be marked on the surface with chalk. Target ships could evade by turning, just like real world ships.

The weakness of Pratt's game is in figuring damage. Yes, the system did allow weaker ships to bring down a pocket battleship, but it was complex and abstract. Each ship had a point total. This number was based on calculations using number and caliber of guns, torpedo tubes, armor, speed, and displacement. As hits were scored, points were subtracted and speed and guns reduced in proportion. This is abstract and unrealistic. Also it calls for a complex card with the numbers laid out in a table. One of the available playing aids is a set of ship's cards already calculated. They go back to the American Civil War and up to World War II.

In summary, morale and commander's characteristics are not in the rules. The firing and torpedo rules feel very authentic. The damage rules are complex and abstract. Remember this is a set of rules developed in the 1930s, and at that time they were state of the art. We have come a ways since then.

Scenarios

Let's start with a refight of the original battle. Weather seems to have been mild, light wind and bright sun. You may choose to introduce weather as a variable. I'll stick to the commanders and their battle plans. This is set up so both sides can be programmed, or a soloist can write orders for one side; then roll dice to select the orders for the other.

Force G made up of Exeter, Ajax, and Achilles. Commodore Harwood. Mission to locate and destroy commerce raiders like Graf Spee. Roll a D-6. 1,2 = option one. 3,4,5,6 = option two.

Option One. Plan an all out attack on any commerce raider. Exeter will take one flank with Ajax and Achilles taking the other. This is intended to force the enemy to divide his fire. Both forces will try to close with the enemy and destroy him. This is the battle plan used. At the time it looked like a wild gamble.

Option Two. In the event of contact with a commerce raider the force will divide and try to keep out of the enemy's effective gun range. Shadow the enemy until reinforced by more powerful ships. Perhaps close for a night torpedo attack. This was essentially the standard procedure at the time. In both cases the admiralty would be notified by radio of the location of the Graf Spee. Note that the powerful reinforcements were days away.

The Graf Spee Captain Langsdorff commanding. Mission to disrupt commerce and tie down naval forces in a wide-ranging search. Roll a D-6. 1,2 = Option A. 3,4 = Option B. 5,6 = Option C.

Option A. Close with the enemy and fight it out. Sink the Exeter. At your discretion (or a die roll of 1,3, or 5) continue to engage until the others are also sunk. If you elect to disengage, roll 2 x D-6 and use the clock system to select your course.

This is more or less what Hitler thought should be done. He wanted a war ship to fight. Admiral Raeder did not buy it. He argued that a commerce raider was too valuable to risk losing for a mere cruiser or two. My thought is that this only works if the Graf Spee can destroy all three cruisers and get away. Otherwise she will be located and probably wounded, a sitting target for the more powerful ships closing in.

Option B. Close with the enemy and engage. Try to take out the more powerful foe, Exeter. If the battle goes badly (die roll 1,3,5 after 20 minutes of action), break off and try to escape. This is roughly what Langsdorff did. Maybe you can come up with a better morale/decision rule.

Option C. As soon as you identify the enemy, turn away and try to keep the enemy at long range. Your guns can destroy the enemy before they can get theirs in range. Use that advantage. If the battle runs into the night, you may decide to evade. (D-6 die roll. 2,4,6)

Churchill suggests this approach in his World War II history. It takes advantage of the Graf Spee's superior guns, but if the cruisers are able to shadow from beyond gun range there are problems. Note that the Ajax had an airplane that could fly to help observe. Graf Spee needs to either sink or shake her pursuers.

Depending on the outcome of the above battle, you might want to follow up with a map exercise tracking down and finishing off the Graf Spee. I'll leave the design of that game to your ingenuity. Featherstone offers some ideas for campaigns like this. Maybe it could be the basis for a Lone Warrior article.

For me the most interesting question is what would have happened if the Graf Spee tried to break out of Montevideo? Langsdorff had telegraphed headquarters that". . escape into open sea and break through to home waters hopeless. . . .", but he believed that reinforcements had arrived for Force G. If he had tried to break out, he would have been faced by Ajax, Achilles and Cumberland. Ajax and Achilles were somewhat damaged and low on ammunition. Cumberland had come from the Falklands and was undamaged, with a full supply of shells and eight eight-inch guns, two more than Exeter. See the ship statistics on ammunition to see what each ship had.

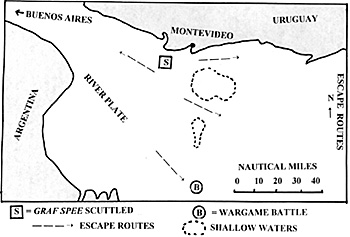

The Graf Spee was damaged but able to make 24 knots when headed for port at Montevideo. Since then she had been under repair for three days. Ammunition was down to about one third of a full supply, but all guns were working. There were a number of possible escape routes. See the map of escape routes. There is little chance that the Graf Spee could escape undetected. No doubt British observers kept a constant watch on her from shore. Also Force G had an observation airplane and the ships were stationed to observe the various escape routes. They could not be too close to shore because of Uruguayan sensitivity about territorial waters. This means they were somewhat dispersed.

There were three possible destinations with some options about routes. The Germans considered a run to Buenos Sires, Argentina about 60 miles further up the river. They hoped for more sympathetic port authorities there. Langsdorff clearly had heading home on his mind. He could have moved along the coast and north into the Atlantic to try for Germany. The least likely option was heading south, but it was a chance. The German supply ship Altmark was still at large and could meet the Graf Spee in the south Atlantic. Then with luck, the Graf Spee could evade the hunters and wait for summer weather on the north Atlantic to return home.

My map of escape routes shows some other information. I gave each route a number or numbers to reflect the odds that Langsdorff would use it. The northern route got 1,2 because he clearly wanted to get home and that was the most direct route. The Next route south got 3 and the most southern got 4. The route to Buenos Aires got 5. If I rolled a 6, I rolled again. I positioned my three ships, one at each of the exits into the Atlantic. My strongest ship Cumberland with her 8-inch guns at the northern route, Achilles on the middle route, and Ajax on the southern end. I tried to place them out of waters claimed by Uruguay. This disposition left the route to Buenos Aires open.

I figured that if the Graf Spee ran to Buenos Aires it was just that much deeper in the bottle. The object was to keep her from escaping again to become a menace to shipping. This probably is not the way a real naval officer would do it but I will do some other dumb things in this game as well. Real naval experts are welcome to send their critique to Lone Warrior.

Game procedure was simple. I rolled a D-6 to determine which exit the Graf Spee would use. Then I figured travel times and placed ships on the table at the meeting point. See my battle map. The Graf Spee moved first, then British ships moved, and both sides fired. I figured firing results then repeated the cycle. I show movement speed and gun range in my table of statistics for each ship.

I used a modified Fletcher Pratt system for firing. I made my estimate of ranges in centimeters. Then I rolled a D-6 to modify the estimate: 1,2 reduce by 2 cm., 3,4 no change, and 5,6 add 2 cm. This was my way of avoiding bias in my estimates. I used pennies to mark the splash marks. To determine damages I used a modified rule from Rules for Wargames. Each time there was a hit, I dealt a card. [I had a deck of clubs only.] Each card stood for a certain kind of damage. For example, a 7 stood for a hit on the bridge with results being loss of control and reduced speed. I adjusted some results to reflect the fact that the Graf Spee was already weakened from the earlier battle.

I diced for the time the Graf Spee would leave harbor. I used a D-12, which came up 4. The Graf Spee was programmed to run straight ahead. I commanded the cruisers, very ineptly too I must say. What follows is my account of the battle written just after the action. See also my battle map.

The Graf Spee moved out of the harbor al 1600 hours. It soon became evident to observers that she was headed south probably to break out and rendezvous with her supply ship.

Since I had stationed Cumberland at the north channel, this meant that the Ajax and Achilles would face her alone at first. The Cumberland made time toward the battle and would join in a few minutes. The Ajax and Achilles moved toward the Graf Spee in line abreast formation, one on each side of the Graf Spee. The German shells fell short, but both cruisers scored a hit. One shot clipped off some superstructure causing no significant damage. The other round hit the hull and caused the Graf Spee to slow down. Some of the hull repairs were done with wood; this was probably a factor in the puny 6-inch guns being able to inflict such damage. The Graf Spee passed between the two cruisers and inflicted a hit on the bridge of the Achilles. Achilles ran out of control and slowed. Ajax had turned out of range to get on a course parallel to the Graf Spee. At this point it looked as if the Graf Spee would evade and break out. But the Cumberland appeared and laid a salvo cutting through the Graf Spee. One shot hit the bridge and the other hit the engine room. The Graf Spee was dead in the water. At that point the battle was over.

In 1939 the Battle of the River Plate was a big event. In a few months even larger battles would be raging and the memory of this relatively small battle would fade. The popular interest in Fletcher Pratt's wargame would also fade as the war raged on. Today the story seems only a minor incident in World War II, but I found it an interesting historical puzzle and a challenge to wargamers.

More Death of a Pocket Battleship

-

Graf Spee: Introduction

Graf Spee: Historical Account

Graf Spee: As a Wargame

Graf Spee: Characteristics and Models

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #132

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com