The Admiral Graf Spee was designed to comply with limits put on the German Navy by the treaty of Versailles ending World War I. The Germans were limited to ships of 10,000 tons or less. Their ship designers developed a new kind of ship to stay within that limit and still be a powerful weapon. In English they were called pocket battleships. They combined the speed of a cruiser with strong armor and the big guns of a battleship. The Germans also cheated. The Graf Spee actually weighed well over 10,000 tons. Her speed was 26 knots, armor belt four inches thick and she had six eleven-inch guns. In 1934, when she was launched, there were no battleships that could catch her and few cruisers that matched her firepower. There were only three British and two French battle cruisers that were an even match.

When war broke out in 1939, the Graf Spee was already in position in the south Atlantic ready to begin commerce raiding. The mission was to attack merchant shipping and avoid contact with naval ships. This would disrupt the flow of supplies to Britain and force the British navy to tie down dozens of warships protecting freighters and hunting for the Graf Spee. Captain Langsdorff, who commanded the Graf Spee, was a capable and humane man. He scrupulously observed the rules of war and never killed a single merchant seaman. Freighter crews were taken prisoner and generally treated well. The Graf Spee managed to take nine merchant ships, capturing two and sinking the rest.

From September 30 to December 7, 1939 the Graf Spee roved the south Atlantic in an elusive voyage. Langsdorff would sink or capture a ship then move far away before he struck again. Both the British and French navies were scouring the seas to find the Graf Spee and other commerce raiders. The hunt ranged over the south Atlantic and even into the Indian Ocean. In an age before satellite imaging, radar, and long-range reconnaissance planes, the search tied down dozens of warships. Meanwhile the flow of food and war material was disrupted. It was an ocean-wide game of hide and seek played for very high stakes.

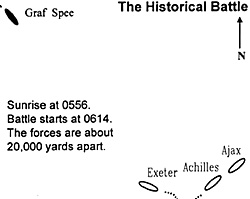

The Graf Spee was located about dawn on December 13, 1939. Langsdorff spotted a ship and headed towards it. It was quickly identified as the British cruiser Exeter. Langsdorff thought the Exeter was escorting a convoy. He planned to fight his way through to the convoy, but first he would have to deal with Exeter and two smaller ships, identified in the dawn light as destroyers. Five minutes later the two were identified as light cruisers Ajax and Achilles. Langsdorff kept Graf Spee closing with the cruisers and opened fire at 0618.

The British had identified the Graf Spee just minutes earlier. At 0614 the Exeter had signaled, 'I think it is a pocket battleship." With that, task force G under Commodore Harry Harwood began to attack. The Exeter turned to one side and the Ajax and Achilles took the other side. They would match the Exeter 'S 8-inch guns and the 6-inch guns of Ajax and Achilles against the 11-inch guns of the Graf Spee. At the time, expert opinion held that the cruisers were no match for the pocket battleship, but Commodore Harwood had planned this battle and even practiced the signals and maneuvers for it. This was a daring gamble against the odds.

In the early fighting, the Exeter took a fearful pounding from the Graf Spee's 11-inch guns. One shot wiped out the B gun turret and destroyed the bridge. The captain survived and had to move to a rear station and pass orders to guns and helm through a human chain. Soon A turret was on fire and Y turret lost electric power. By 0740 the Exeter had only one gun firing, was on fire and was hit in the hull. She would soon withdraw.

The Ajax and Achilles were on the other flank charging the Graf Spee. Their 6-inch guns could not penetrate the Graf Spee's armor belt, but they could do damage to superstructure and crewmen manning secondary guns. One 6-inch bit started a fire on the Graf Spee. Some 8-inch shells had pierced the hull of the Graf Spee above the waterline. At one point a hit near the bridge stunned Langsdorff knocking him unconscious for a few minutes. But as the two light cruisers closed range the Graf Spee turned her 11-inch guns on them. The Ajax took a shell and lost her X and Y turrets. The cruisers launched a spread of torpedoes, but the Graf Spee spotted them and turned to avoid them.

About 0640 the Graf Spee had turned and was no longer closing on the cruisers. At 0740 Harwood pulled his two cruisers away to shadow the Graf Spee at long range. It soon became clear that Langsdorff was heading for the neutral port of Montevideo, Uruguay. There he would try to repair his ship.

The Graf Spee had lost 36 dead and had 6 seriously wounded. There was a hole in the bow above the waterline. Langsdorff was convinced that hole made his ship unseaworthy if he took it into the north Atlantic. The galley was ruined and there were several other items damaged. The Graf Spee had used 60% of its ammunition. As she retreated, she was hounded by the Ajax and Achilles.

Commodore Harwood had released the Exeter to withdraw to the Falkland Islands for repair. He had signaled the location of the Graf Spee to all Allied forces. Eventually reinforcements would arrive, but until then Ajax and Achilles had to stay in contact with Graf Spee. The cruiser Cumberland was at the Falkland Islands and was steaming to join the chase even before the battle ended. From time to time the Graf Spee would fire her big guns to keep the cruisers at a respectful distance, but the chase lasted all day and into the night. The Graf Spee dropped anchor in the Montevideo harbor 2330 hours. Now the issue was in the hands of diplomats.

Montevideo was a neutral port, so the situation was touchy. Warships from belligerent powers could use neutral ports to make repairs to restore their seaworthiness but not to restore their fighting capacity. Uruguay was not happy about the fact that part of the fighting took place in their territorial waters. However, neither Britain nor Germany recognized the Uruguayan claim over those waters. The British began to pressure Uruguay to force the Graf Spee to go to sea, as did the French. There was a good deal of hypocrisy in this. The last thing Commodore Harwood wanted was to face the Graf Spee with his two cruisers. Delay would work in his favor, allowing the cruiser Cumberland to arrive and with even more delay the Ark Royal and Renown would arrive. The Cumberland did arrive shortly and British intelligence planted reports that the Ark Royal and Renown had arrived as well. Both the United Press and the German news services reported that Ark Royal and Renown had arrived.

Meanwhile Captain Langsdorff and the German diplomats were making their case to the port authorities. Langsdorff asked for fifteen days to repair his ship, listing needed repairs.

The port authorities sent a technical commission to inspect the Graf Spee. They reported 15 holes on the starboard side and 12 holes on the port side. Damage to the galley seemed minor; "one cooking cauldron, pipes and electric equipment" were damaged by a shell. They concluded, "provisional repairs can be carried out in three days." The Graf Spee got seventy-two hours in port. After that it would have to take its chances at sea.

Langsdorff contacted Berlin and was told it was his decision. He was not to allow the ship to be seized by Uruguay. He could either fight his way out or scuttle his ship. He chose to scuttle. A skeleton crew moved the Graf Spee out of port and blew it up. A few days later Langsdorff shot himself.

His decision to scuttle was based on the following factors. Most important, he believed that a superior naval force was waiting for him if he left port. He could try fighting his way out and risking the loss of his ship and the capture of its remains. This would give the British valuable intelligence. Scuttling would destroy the ship thus denying the British the intelligence and it would save lives. Langsdorff was a humane man; those lives would weigh heavily. Even if he won his battle to break out, he was very low on ammunition and he repeatedly said his ship could not stand the storms in the north Atlantic. The north Atlantic had to be crossed on the way home. Whatever happened off Montevideo, the game was up.

More Death of a Pocket Battleship

-

Graf Spee: Introduction

Graf Spee: Historical Account

Graf Spee: As a Wargame

Graf Spee: Characteristics and Models

Back to Table of Contents -- Lone Warrior #132

Back to Lone Warrior List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Solo Wargamers Association.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com