The picture for 14 July, then, was one of American regiments and battalions segregated by the jungle terrain into squad- and platoon-size formations which, relying on inaccurate maps, were milling around thick jungle on either side of a spur of the Torricelli chain, which stretched irregularly about 3,600 meters north of Afua between the Driniumor and Koronal Creek.

The Japanese, simultaneously, had two understrength infantry regiments consolidating positions on that very spur near Kwamagnirk Village. Conceivably, squads of Americans and Japanese passed within a few meters of each other, but enclosed and muffled by the great trees and expansive vegetation, they passed unaware of the presence of the other. Had they even glimpsed another patrol several meters away, the jungle had reduced all their uniforms and national identities to a sameness.

The Japanese infantrymen had picked up numerous pieces of American clothing and equipment, probably after overrunning Company E and forcing G to withdraw. A 2d Squadron security patrol, for instance saw four Japanese near River X wearing American packs and clothing. As early as 29 June the Persecution Task Force S-2 warned all units that the Japanese were wearing U.S. uniforms and equipment and to be careful "not to identify the enemy by clothing alone." [53]

Members of the 112th were reduced to the fatigues they wore on their backs. Clothes and boots rotted away, because in the harsh priorities of combat, they were less essential to survival than ammunition and food. The 112th would spend the next three weeks fighting along the Driniumor. The only relief was for the seriously ill or the wounded. The living and the dead stayed on the line.

That night, General Hall declared a full alert because a Japanese prisoner had claimed that a major attack was imminent. The 112th had special cause for concern because a few hours earlier Persecution Task Force Headquarters had informed them by message that approximately two Japanese regiments were about 3,600 meters northwest of the 112th's right rear. [54]

The anticipated attack never materialized, and only light small arms fire was audible to the north.

Another reason that American patrols encountered so few Japanese on 14 July was that the Japanese were still regrouping. The 78th and 80th Infantry regiments, which had suffered such terrible casualties on the night of 10-11 July, amalgamated themselves

under the command of Maj. Gen. Miyake Sadahiko and henceforth were known as

Miyake Force. Also on 14 July, 18th Army Headquarters apparently realized the serious losses incurred to date. General Adachi then recognized that the Americans had reoccupied the original Japanese crossing point on the Driniumor, that strong enemy units were advancing along the coast against his 237th Infantry, and that for the first time to his knowledge, Americans were appearing in strength on the Afua front. He responded to the new situation by ordering the 41st Division to destroy the Americans near the Driniumor crossing and along the coast. Meanwhile, he directed the 20th Division to annihilate the enemy near Afua. [55]

The 112th Cavalry was in the midst of its counterattack, but the men could account for little but frustration, confusion, and needless death from "friendly fire." Persecution Task Force was dissatisfied with the 112th Cavalry's seemingly slow and overly cautious advance. General Hall wanted the gap in the U.S. lines closed.

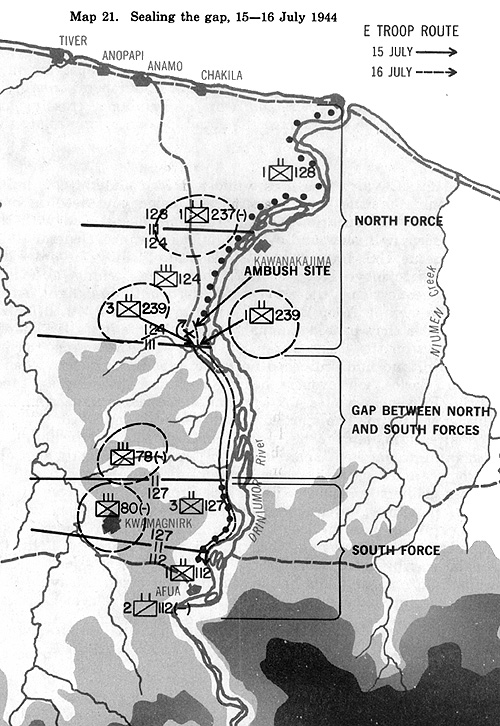

At 2300 on 14 July, he ordered General Cunningham to move Troop E north to fill the opening, although he did agree to a request that the move be delayed until first light. At dawn on 15 July, the men of Troop E started north to find the 124th Infantry. About one hour later they passed Company L, 127th Infantry's left (north) flank, which rested on the exposed gap (see map 21). Afterwards, they used the Anamo Trail and had proceeded north perhaps 2,700 meters when the lead scout, Pfc. Carlos A. Provencio, heard a Japanese dragging a weapon along the trail. Provencio waited for the man to appear on the trail and, when he did, shot at him.

The startled Japanese turned and fled. The point man moved after him, and as he turned another twist on the jungle path, he almost ran into another Japanese soldier, whom he promptly shot and killed. The troop reacted quickly, moved forward firing in support, and killed six Japanese soldiers. [56]

Private First Class Provencio then caught sight of a Japanese machine gun emplacement, so instead of going straight along the trail towards the gun, he led the troop on a detour around its right flank. The Americans then resumed their march and reached the 124th Infantry's command post by noon. Shortly thereafter, Troop E sent a message to General Cunningham reporting this linkup, but it never arrived, leaving the general to wonder what had happened to his men. The cavalrymen spent the rest of the afternoon exchanging stories and food with 3d Battalion, 124th Infantry. At 1700, that battalion received orders to attack south to close the gap, but with darkness fast approaching, a request to postpone the attack until

morning was granted.

While Troop E made its way north, patrols from the 112th Cavalry reported numerous sightings of small parties of Japanese south and west of the regiment's positions near Afua. General Cunningham, in some distemper, readjusted his lines northward to cover the void created by Troop E's departure. [57]

Other cavalrymen improved defenses around Afua, sweating under the tropical sun. Three C-47s flew over and dropped rations and ammunition, for Japanese ambushes had made ration trains too dangerous or too prohibitive in terms of the men needed to guard the trains, which of necessity moved slowly along the easily ambushed jungle trails. Usually the airmen dropped ten-in-one rations, but for one three-day period, the cavalrymen on the ground

had to subsist on K rations alone. [58]

Members of the 112th's Service Company like T-5 Albert Earl Gossett

volunteered to ride in the C-47 ration planes and to kick supplies out the doorless side of the aircraft. It was the kind of effort that could easily be overlooked, but without resupply the combat troops would be unable to function. An idea of the magnitude of the airdrop may be gained from the statistics that 5.1 tons of supplies were air-dropped on

22 July to the 112th at Afua, and just two days later, another 3.1 tons were parachuted to them. [59]

Kicking out supply pallets was dangerous work, because in the excitement of the few seconds one had to kick the supplies out, it was deceptively simple to get tangled in the parachute static lines and pulled from the aircraft. On the ground, after eating, 112th personnel settled in for the night. It passed quietly with only desultory firing heard to the north. But there was always potential danger. A friendly artillery battery firing a routine night interdiction mission had one stray shell explode in the riverbed about fifty meters in front of Troop G's sector, killing a trooper who had decided to sleep above ground that night.

On 15 July the Japanese 20th Division reported that in its sector "almost all" the enemy had retreated and that its troops were "pursuing and mopping up" the Americans. Evidently, the 78th and 80th Infantry regiments of the 20th Division had as little notion of the whereabouts of the 112th Cavalry, 127th Infantry, and 124th Infantry as the Americans had of Japanese locations.

That day, General Adachi decided to send the previously uncommitted 66th

Infantry, 51st Division, to expand the 20th Division's gains. Concurrently, he ordered the 41st Division's 239th and 237th Infantry regiments to attack west and east, respectively,

in order to hold the original Japanese breakthrough corridor on the Driniumor. [60]

While Troop E and the 124th Infantry would be attacking south and the 112th Cavalry and 127th Infantry pushing north, the convergence of Americans and Japanese units from all points of the compass would create a unique tactical situation and make a collision unavoidable. It happened the morning of 16 July.

Troop E spent the night of 15 July with Company I, 124th Infantry. Supply Sgt. Frank Salas recalled that the 124th's men were "very happy" to see fellow Americans. The 124th Infantry had had no combat experience, and the sight of the 112th Cavalry men, veterans of New Britain, calmed the understandably nervous green troops. The Company I commander distributed E troopers throughout his unit, which occupied the right (south), or exposed, flank of the battalion. He acknowledged the "steadying

influence" of the cavalrymen the next morning, when he told Lieutenant Campbell, then commanding Troop E, that it was the first time Company I's soldiers had not opened fire at shadows and noises during the night. In the still cool morning, some of the cavalrymen and infantrymen were sitting

around cleaning their weapons for the upcoming attack. An advanced detachment from Troop E began moving across a clearing. In the jungle vegetation on the south side of the clearing, about fifty Japanese troops from Major Harada's 1st Battalion, 239th Infantry, lay in ambush. As the Americans approached, a nervous Japanese machine gunner tripped the ambush too soon. Machine gun fire raked a knoll just below the feet of the

surprised E troopers. No Japanese could be seen, but puffs of smoke and rifles were visible in the jungle foliage. The new men stood frozen in amazement that live Japanese could be only twenty meters away, but the 112th veterans ran back into the perimeter and opened fire.

Manning weapons belonging to the 124th Infantry, Cpl. T. D. Clark and Pvt. Jasper Fortney fired into the thicket. Clark used a machine gun, and Fortney fired a 60-mm mortar without a site. About ten meters closer to the Japanese, another E trooper adjusted the mortar fire because he could see movement in the trees. The mortar shells seemed to go straight up to apogee and then plunge back to earth. The firing continued for about thirty minutes, and then the surviving Japanese rushed the Americans, who promptly shot them down. [61]

Troop E searched the bushes for any Japanese survivors. Discovering none, they spearheaded the 3d Battalion's push south. Meantime, the Japanese 3d Battalion, 237th Infantry, attacked the rear of the 3d Battalion, 124th Infantry, temporarily separating it from Troop E. Nevertheless, the cavalrymen pushed slowly south against only occasional sniper fire and contacted Company K, 127th Infantry, at 1245 and then proceeded on to the troop bivouac near Headquarters, 2d Squadron. During their battle,

forty-five Japanese infantrymen were killed, including Major Harada. The 112th Cavalry miraculously suffered no casualties. This action of 16 July forced General Adachi to reconsider the forces arrayed against him.

Chapter 6: Counterattack

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com