The multiple invasions caught the Japanese Eighth and Second Area armies completely unprepared, the former expecting an invasion of Rabaul, the latter an Allied landing near Madang.

1st wave, Aitape, Dutch New Guinea.

SWPA's successful deception effort thoroughly baffled the Japanese, who although warned by aircraft sighting reports of two Allied convoys moving north of the Admiralties, were unable to predict the exact objective of these armadas. On 21 April, one day before the landings, hundreds of American and Australian aircraft struck Hollandia, Aitape, and the Wakde-Sarmi vicinity. The magnitude of the strikes was such that local Japanese forces in each area believed that

their sector was the main invasion target. [21] In addition to the obvious last-minute deception value of the air attacks, marauding Allied aircraft also destroyed the remnants of Japanese air strength in the region and guaranteed Allied air superiority throughout the subsequent campaigns.

The main American landings at Hollandia met only scattered Japanese

resistance. At Aitape, Persecution Task Force, commanded by Brig. Gen. Jens A. Doe,

landed more than 12,000 men, about 7,000 of them combat troops of the 163d

Regimental Combat Team (RCT), reinforced. They encountered no resistance as the nearby Japanese rear service support troops fled into the jungle. By dusk U.S. troops had taken their primary objective, the three airfields at Aitape, known collectively as the Tadji Drome. Engineer troops who had accompanied the landing forces quickly set to work rehabilitating the airfields.

This was the first major landing in which units from the 3d Engineer Special Brigade participated. The 27th Combat Battalion, discovering no Japanese mines or booby traps, worked mainly on widening roads and strengthening bridges to support M-4 medium tanks. [22]

Three Royal Australian Air Force mobile works (engineer) squadrons had a

fighter strip operational within two days of the landing, but heavy rains and poor drainage soon turned their labor into a quagmire. Work at a nearby bomber strip proceeded more slowly, even after the arrival in early May of the 872d and 875th American Airborne Aviation battalions. In fact,the bomber strip was not ready for use until early July, by which time the need for it

had been overtaken by events.

The engineers (40 percent of the invasion force) also unloaded seven Landing Ship Tanks (LSTs) the first day and began constructing roads. Unloading was slowed by the lack of Landing Craft Mediums (LCMs). Only eight LCMs and one Landing Craft Tank (LCT) were available to unload the cargo ship, auxiliary (AK) Etamin, which remained stationary, unloading its cargo near the beachhead.

[23]

On 28 April, a lone Japanese aircraft slipped through the air defense net and bombed and damaged the Etamin, forcing it to scuttle its cargo in order to remain afloat.

Ordnance support units consequently lost all their tools and spare parts.

[24]

To add to the confusion, as their tension broke after the unopposed landings, the troops became very nonchalant about their personal belongings. Pilfering was common, and within twenty-four hours of the invasion, individual rations littered the entire beach. Soldiers discarded so many items of equipment and ammunition, especially hand grenades, that one officer later commented on their "strong lack of discipline" and the need for more guards and military police to maintain order on future

beachheads. [25]

Moreover General Doe felt that the commander of the 163d Regiment was not moving quickly enough to secure his flanks. His tardiness ultimately led General Doe to recommend, and Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, commander, 6th Army, to approve, the relief of the 163d's commander. He remained in command only until the 163d had been withdrawn to participate in the Wakde-Sarmi operation, 400 kilometers northwest of Aitape. General Krueger's

Ultra-derived knowledge of Japanese weakness near Aitape might have facilitated his concurrence in the relief of the overly cautious regimental commander.

In any case, the 32d Infantry Division, veterans of the vicious Buna fighting, relieved the 163d RCT in early May. The 32d Division had trained and reorganized in

Australia for seven months after Buna. Their training schedule stressed living in a jungle environment, individual combat training both day and night, basic and advanced amphibious training, and unit training, including night exercises.

[26]

The division's 127th RCT had landed at Aitape in late April, and the rest of the division, less the 128th Infantry Regiment,

arrived on 4 May. The 128th remained in Alamo Force (6th Army) reserve at Saidor until 15 May, when it too went to Aitape.

Maj. Gen. William H. Gill, commander of the 32d Division, also assumed command of Persecution Task Force. Gill, a Virginian and a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, was fifty-eight years old. He was a decorated World War I veteran with extensive staff and command experience and had commanded the 32d Division since March 1943. Gill dispatched elements of his 127th RCT to push eastward to uncover the whereabouts of General Adachi's 18th Army and to learn its intentions.*

At the same time, other battalions from the regiment would patrol and prepare defensive positions. Minor patrol skirmishes aside, the first prolonged engagement fought between Company C, 127th RCT, and the Japanese 78th Infantry Regiment, 20th Infantry Division, erupted on 14 May near Marubian, about fifty kilometers east of the landing beaches. The inconclusive fight and the distance from potential reinforcements convinced General Gill not to push farther east. [27]

As the Americans probed the Japanese forces, the Japanese scouted American units. On 10 May, 18th Army sent four long-range reconnaissance platoons westward to gather intelligence about American dispositions, to obstruct American efforts to collect battlefield intelligence about 18th Army, and to reconnoiter American entrenchments and positions near Aitape. [28]

These Japanese troops probably ambushed a U.S. ration train on 31 May and clashed with the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, near Afua in early June. As both sides stepped up their patrol activity, clashes were bound to occur. A particularly sharp battle broke out near Yakainul, about thirty kilometers east of the beachhead where, from 31 May through 6 June, casualties on both sides exceeded one hundred killed and wounded.

[29]

Increased sightings of Japanese patrols east and west of the Driniumor

continued into early June, as it became abundantly clear that 18th Army was nearing Aitape in force. General Gill decided to protect the Tadji airstrip by establishing an outer defensive line, in the form of a covering force, along the Driniumor River.

Covering force doctrine defined the purpose of such a defensive line as to provide time for the main force to prepare itself for combat, to deceive the enemy as to the actual location of the main battle position, to force the enemy to deploy early, and to provide a deeper view of the terrain over which the attacker would advance. [30]

If forced to withdraw, the covering force was expected to fight a delaying action against the enemy attacker. Covering force doctrine for jungle operations had languished. The 1944 version of the Jungle Warfare Manual restated verbatim chapters from the 1941 edition on retrograde movement and delaying action. That meant that the 112th Cavalry Regiment

and the 32d Infantry Division were ordered to conduct operations according to a doctrine that had officially remained unchanged despite nearly three years' combat experience in jungle warfare. [31]

Nonetheless, Gill's decision was consistent with his principal mission, which was to protect the Tadji airfields against Japanese attack. The inconsistency lay in the doctrine and the small number of troops available to defend an extended river line in jungle terrain.

By doctrinal theory, a rifle battalion in the defense would be assigned frontage of 900 to 1,800 meters, depending on the defensive strength of the terrain. [32] The depth of such a defense would vary from 720 to 1,260 meters. In theory, the defense of a river line with extremely wide frontages corresponded to any defense on a wide front, depending on the type of terrain. Again, according to the manual, if the terrain at the riverbank was unsuited for close defensive fires, the main line of resistance might be withdrawn from the river to obtain improved fields of grazing fire.

In practice, on 7 June 1944 the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, held a 1,800-meter front running south from the mouth of the Driniumor. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, defended a 3,300-meter front that extended north from the vicinity of Afua. Patrols covered the approximately 2,700-meter gap between the units. [33] The two rifle battalions were greatly overextended

and, given the jungle terrain, were in fact isolated. Japanese reconnaissance patrols easily

infiltrated through the porous American lines.

These Japanese long-range patrols were so successful at remaining undetected

deep behind the U.S. front lines that the Americans thought that Japanese reconnaissance patrol activity near the Driniumor had slacked off in early June. The stealth of the reconnaissance patrols contrasted sharply with the bold activity of Japanese fighting patrols, whose ambush and surveillance tactics proved singularly effective in preventing American reconnaissance patrols from crossing Niumen Creek, about 2,700 meters east of the Driniumor.

Nevertheless, the combination of ground activity, patrol reports, and aerial reconnaissance, combined with Ultra, revealed that 18th Army was inexorably moving west. Sixth Army's May "Summary of Operations" noted the increasing Japanese pressure on Persecution Task Force's eastern flank and warned that the enemy had "strong forces" moving towards Aitape. [34]

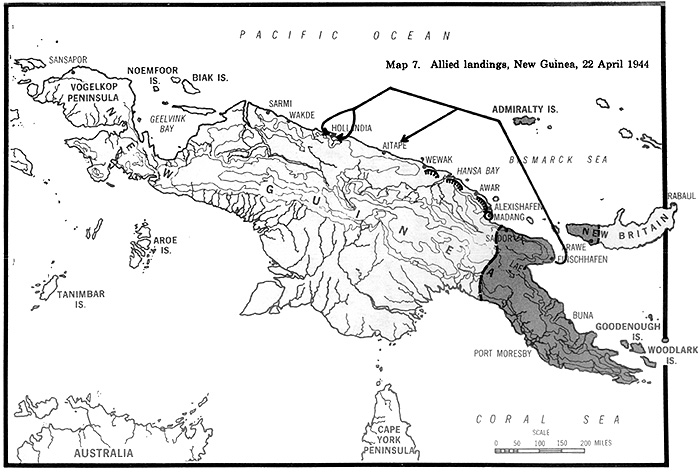

The combined Hollandia-Aitape operation was the largest SWPA operation to

date, involving 217 ships, nearly 80,000 men, and their supplies moving more than 1,700 kilometers to conduct three simultaneous amphibious landings (see map 7). [20]

The combined Hollandia-Aitape operation was the largest SWPA operation to

date, involving 217 ships, nearly 80,000 men, and their supplies moving more than 1,700 kilometers to conduct three simultaneous amphibious landings (see map 7). [20]

Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger.

*Ultra intelligence (identified as such) was not supposed to be disseminated below army level, and even there distribution was restricted. But 6th Army pointed out that in the Pacific theater, corps operated as armies did in the European theater and that corps in the Pacific could thus receive Ultra intelligence. Moreover 6th Army also disseminated Ultra-derived intelligence in sanitized (source concealed) form to army, corps, and division staffs via the SWPA G-2's so-called Daily Summary, a secret-level daily intelligence bulletin. See SRH-107, "Problems of the SSO System in World War II," 30-31, and Brief History, 18.

Chapter 2: American and Japanese Operational Deployments

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com