The 22 April Allied landings at Aitape and Hollandia naturally provoked an immediate Japanese reaction. Lieutenant General Adachi thought that if he attacked at Aitape with the entire 18th Army immediately, he might be able to break through the American defenses there and move on to seize Hollandia. Given the condition of his troops and the enormous distances involved, it is doubtful that even Adachi seriously believed such a grand scheme was possible. More likely he reasoned that, at the very least, a counterattack would retard the enemy's westward advance and thereby contribute to the overall operations of Second Area Army. [35] Adachi hoped to cooperate with Second Area Army, which could attack the beachheads from the west as 18th Army attacked them from the east.

General Anami, commander of the Second Area Army, already had ordered two battalions of his 36th Infantry Division, located near the SarmiWakde area, eastward to check the Allied landing at Hollandia. When he received Adachi's signal outlining 18th Army's plan, Anami was receptive to the concept of a pincer attack against the invaders. Consequently, on the night of 24 April, Anami alerted the entire 36th Division for an attack against Hollandia. In the midst of these preparations, Anami transmitted his

intentions to Southern Army at Singapore. Unless the Japanese could retake Hollandia, he warned, it would jeopardize Second Area Army's future operations.

Southern Army and IGHQ, however, disagreed with Anami's assessment and,

rather than endorse the Hollandia attack, instead ordered Second Area Army to prepare against possible future Allied attacks in western New Guinea and the approaches to the Philippines and Palau, as well as against raids by Allied task forces against the western Caroline Islands. Moreover, because of Allied air superiority, IGHQ was reluctant to

commit ground forces to the Hollandia counterattack without adequate air cover. The Imperial Navy Combined Fleet also opposed such an operation, deeming it "difficult to expect the Hollandia counterattack to succeed" because of enemy air superiority east of Sarmi, New Guinea. [36]

On 2 May 1944, in consonance with its strategic appreciation, IGHQ ordered 18th Army to move west "as quickly as possible" in order to link up with Second Area Army and thereby to improve Japanese defenses in western New Guinea.

Simultaneously,. IGHQ redefined Second Area Army's primary defense line as extending to the inner part of Geelvink Bay, Manokwari, Sorong, and the Halmahera Islands. The withdrawal of Second Area Army units around Sarmi increased the separation between 18th Army from Second Area Army and made it necessary for Adachi's troops to cover even greater distances to achieve a linkup. In effect, IGHQ had written off 18th Army.

General Anami, however, had not. He continued to advocate a more active defense and

took his case to Southern Army at Singapore, where during a two-day conference on 5

and 6 May, Anami pressed for approval of his plan to counterattack the Allied forces at Hollandia. Reinforcements en route could be used for that purpose.

IGHQ previously had ordered the 32d and 35th Infantry divisions then in the Philippines transferred to western New Guinea in order to reinforce Anami's command. On 6 May, however, U.S. submarines attacked this convoy just south of the Philippines, and the two divisions lost most of their artillery and infantry weapons in the attacks. [37] This latest disaster again forced IGHQ, Southern Army, and Second Area Army to reevaluate Japanese operations in the New Guinea theater.

Anami still wanted the survivors of the two ill-fated divisions sent to his command. IGHQ rejected this alternative because it remained unwilling to send the units to forward combat areas where the Japanese lacked air superiority. Instead, IGHQ again redefined the "primary defense line," this time to exclude Geelvink Bay, although the bay, Biak, and Manokwari were to be held "as long as possible" against Allied attacks. The decision pulled Second Area Army even farther away from 18th Army.

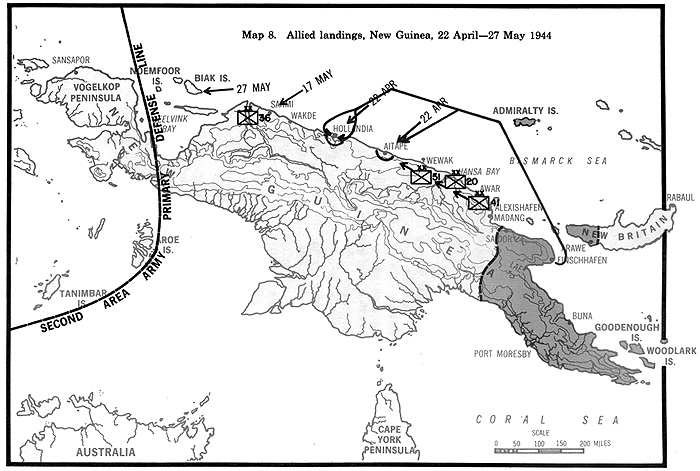

MacArthur's 17 May landings at Sarmi, about 250 kilometers west of Hollandia, put Anami on the defensive, and he had to forsake any plans for a counterattack against Hollandia. Then, on 27 May, the U.S. 41st Infantry Division, less one regiment, stormed ashore at Biak (see map 8). The subsequent loss of Biak cut the last direct line of communication between Second Area Army and 18th Army.

With dogged determination, 18th Army was pushing slowly west. On 15 May,

Adachi had one of his staff officers fly from Wewak to Davao to tell General Anami that he intended to attack Aitape. [38]

The fall of Biak, however, had altered General Adachi's chain of command. Isolated from Second Area Army, 18th Army found itself, on 16 June, subordinated directly to Southern Army by IGHQ. IGHQ also limited Adachi's mission to conducting "a delaying action at strategic locations in eastern New Guinea." [39] That meant Adachi no longer had any military reason to attack Aitape.

Adachi's personal reasons, however, remained. To General Adachi's thinking, 18th Army's entire reason for being a fighting force was inextricably bound to the Aitape attack because of the deployment and the condition of his units. By late June his units had already begun to deploy for battle. The main elements of the 20th Division, for instance, had reached the Driniumor River on 18 June. They had started their two-

month march through the jungle from Hansa, averaging ten kilometers a day. By the

time they arrived at the Driniumor, they were making about half that distance daily.

Their personal hardships on this trek exemplified the enormous difficulties Japanese units had to overcome during this overland move. Adachi could not concede that their hardships had been for naught.

A shortage of all classes of supplies and communications equipment also

plagued 18th Army: a lack of expendable signal equipment, such as battery cells and tubes; shortages of wire cutters (essential for use against wire entanglements), anti-tank equipment, and hollow charge shells for the Type 94 mountain gun and the Type 92 infantry gun; only 300 trucks for the three divisions; and but twenty-seven landing barges to shuttle troops along the coast. [40]

Furthermore, 4th Air Army could provide neither effective air defense nor aerial reconnaissance and aerial photographs to guide the soldiers during their march. Following the destruction of 4th Air Army, the Allied air arms had switched their main efforts to attacking ground troops on the march and in their laager areas. Nearly 800 of the 2,600 tons of Japanese supplies were lost to Allied air strikes.

Individual formations likewise suffered. The 51st Division had only thirty trucks to move its equipment and supplies, leaving the division commander no alternative but to mobilize 1,700 of his combat troops as bearers to carry the division's baggage.

Movement along coastal waterways became exceptionally dangerous as Allied aircraft, PT boats, and warships made numerous forays to interdict these transportation routes. Everyone realized that no major resupply convoys could be expected. Officers therefore ordered their men to take care of their equipment and clothing; in order to preserve their boots, troops were ordered to go barefoot in rivers and swamps and to wear tabi

(thick-soled stockings) in camp instead of the precious boots.

[41]

The move by the 2d Battalion, 80th Infantry Regiment, illustrated in microcosm the extent of 18th Army's problems. On 20 June the battalion neared the Driniumor and sent scouts to reconnoiter the so-called Paup Hamlets, four small native villages. About 1400, an American fighting patrol, numbering an estimated thirty to forty men, attacked

the neighboring 3d Battalion's position. Later in the day, Allied aircraft bombed and strafed near the 2d Battalion's bivouac. The next day Allied aircraft continued to bomb and strafe randomly throughout the area. Allied artillery exploded a few hundred meters from the battalion area, but there were no casualties.

On the twenty-fourth, patrols reported that the Americans had established outposts along the Driniumor, and other patrols clashed with American patrols, losing one man killed and another wounded. The 2d Battalion was readying an attack against U.S. positions in the Paup Hamlets for 29 June when it received word from division to postpone the assault because of the delay in moving supplies forward to support the

other combat units involved in the operation. [42]

On 27 June, around noon, Allied aircraft bombed and strafed near the

battalion's positions, and about 0200 on 29 June Allied warships shelled the area. Neither incident caused casualties, but they were disruptive and unsettling. Yet all the 2d Battalion could do was dig in, block American reconnaissance patrols from moving through its area, and await further orders. Meanwhile, malnutrition and disease stalked the Japanese troops with deadlier effects than the Allied shelling and bombing. Despite the hardships, 18th Army had little choice but to move west. Army staff officers estimated that with its normal organization and supply requirement it would be able to remain in the Wewak area until the end of September.

[43]

As 18th Army chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Yoshihara Kane, phrased it, the Japanese could die where they were or die advancing. Both ways were perilous, but the Japanese

finally decided to carry out their duty to the nation. They advanced.

[44]

As early as 5 May, preliminary intelligence reports about American forces at Aitape filtered into 18th Army. The reports, based on extensive Japanese patrolling in the Aitape vicinity, correctly noted that the Aitape airfields were the center of the American position and described a semicircular defensive perimeter about ten kilometers east of the airstrips. Probably because of the lethargic U.S. movement to establish flanks, Japanese patrols reported that the U.S. lines appeared anchored on the Nigia River, about halfway between Aitape and the Driniumor River. This, Adachi decided, was the defensive line he had to capture.

General Adachi's initial plan was simple, but risky. He planned to concentrate all available combat units on a narrow, 500-meter front, to echelon them in depth, and to launch a surprise attack that would penetrate the entire depth of the American defenses.

Following their breakthrough of the American covering force, the Japanese attackers would regroup at Chinapelli and then attack Aitape from the south. Planners estimated that the entire operation would take three days. [45]

Confusion about the exact timing of the attack contributed to conflicting Allied interpretations of Ultra evidence. According to Japanese documents, the attack was to commence in mid-July. That date, however, originally seems to have referred to the second-phase attack planned against the Aitape perimeter after the destruction of covering force defenses. The Japanese initially had set a mid-June date for their attack against the U.S. covering forces supposedly on the Nigia River.

Based on the recollections of an 18th Army staff officer, the attack was indeed to commence in mid-June, but the delays in moving men and supplies through the jungle necessitated several postponements because only about 10 percent of Adachi's forces were in their attack assembly areas by mid-June. The confusion and postponements paradoxically worked to 18th Army's advantage. Ultra provided so much information to 6th Army about the Japanese maneuvers that intelligence analysts might have been unable to see the forest for the trees.

Chapter 2: American and Japanese Operational Deployments

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com