By early 1944 General MacArthur's planners had begun the process that would bring Americans and Japanese to battle in this heretofore remote spot. Aitape was about 200 kilometers east of the major Japanese base at Hollandia, but nearly 650 kilometers west of the nearest Allied ground forces.

It was thus beyond the approximately 500-kilometer operational radius of land-based Allied fighter aircraft and accordingly was lightly defended by the Japanese. Based on their previous experience fighting MacArthur, Japanese planners believed that the next Allied landing would be made between Madang and Hansa Bay. These Japanese estimates were remarkably similar to those of the Combined Chiefs of Staff in Washington.

After the deliberations of Allied statesmen at the Quadrant Conference in Quebec, 14-24 August 1943, the Combined Chiefs approved bypassing rather than capturing the major Japanese naval base at Rabaul, New Britain, and neutralizing the Japanese forces in eastern New Guinea to Wewak, about 160 kilometers east of Aitape. [3]

The decision to bypass Rabaul and to give top priority to Admiral Chester A. Nimitz's drive across the Central Pacific seemed to leave MacArthur in a backwater, far removed from the main action. As D. Clayton James has observed, the disappointing Quebec decisions set MacArthur to thinking of ways to adopt this bypassing or leapfrog strategy to his own operations. [4]

The shaping of MacArthur's strategy was enhanced by the availability of

Ultra-derived intelligence about Japanese defensive preparations. While it remains difficult to demonstrate a direct causal relationship between Ultra-derived intelligence

and MacArthur's leapfrog strategy, it does seem apparent that Ultra was instrumental in

MacArthur's decision to scrap his notions for an invasion of Rabaul in favor of a series

of seaborne flanking maneuvers along New Guinea's northern coast.

MacArthur's Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) Command had its own signals

intercept organization called Central Bureau. Central Bureau, which operated out of Brisbane, Australia, in early 1944, had been activated on 15 April 1942 as a combined Australian-American intercept and decryption service.*

Maj. Gen. S. B. Akin, SWPA's chief signal officer, was the guiding force in Central Bureau's evolution and technical development. By 1943 the bureau had more than 1,000 members and had become a high quality intercept network.

[5]

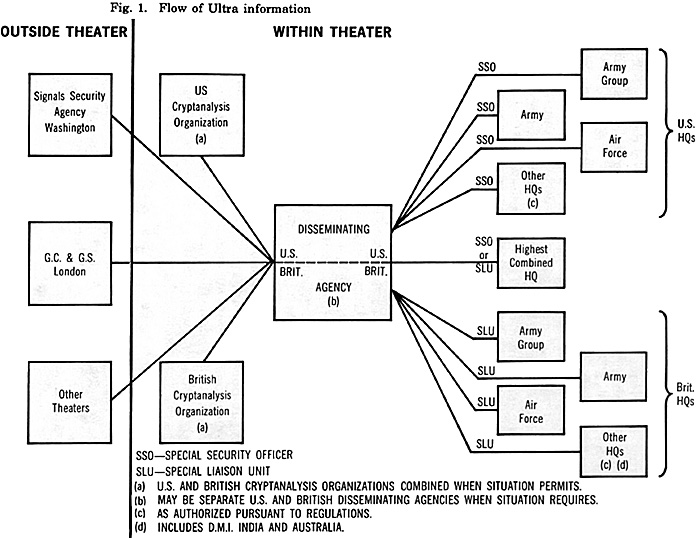

Its Washington counterpart was the Military Intelligence

Service (MIS) headquartered at Arlington Hall Station, Virginia. Friction characterized the relations of these two intelligence organizations, but by early 1944 they were regularly exchanging information, although MIS was never pleased with Central Bureau's and SWPA's seemingly casual treatment and dissemination to field units of Ultra-derived intelligence information (see fig. 1). [6]

Despite Herculean efforts and technical breakthroughs, the complete recovery of Japanese Army codes still defied the Central Bureau's skilled decryptanalysts, and consequently much of the Japanese Army order of battle information depended on the less reliable system of traffic analysis. [7]

Then in late January 1944 the capture of the main Japanese Army codes and ciphers "brought a sudden embarrassment of riches to Arlington Hall, and early in February the Japanese section began to be deluged with a daily flow of thousands of readable Japanese Army messages."

[8]

With the veil shrouding the Japanese 18th Army's dispositions in New Guinea pulled away. MacArthur and his staff were privy not only to enemy order of battle information, but also to the very intentions of Lt. Gen. Adachi Hatazo, commander of that army.

Japanese messages transmitted and intercepted in late January revealed to

SWPA by early February the precise location of each Japanese unit assigned to the

defense of Madang, Hansa, and Alexishafen. Beyond that, Ultra provided the Allies

specific figures on Japanese casualties, personnel shortfalls, and supply shortages,

especially of small arms ammunition. MacArthur's decision to seize the Admiralty Islands on 29 February 1944, one month ahead of the originally scheduled invasion date, was based on his knowledge that Japanese air and sea arms were withdrawing from that area and that there was little to fear from them. [9]

The Admiralty operation, in turn, allowed him to accelerate his drive up the New Guinea coast and provided him air bases in the Admiralties that could support operations along that coast. [10] The acquisition of those bases and Ultra revelations probably led MacArthur to cancel his proposed Hansa Bay operations in favor of a direct jump to Hollandia. [11] A decrypted Japanese message, transmitted 28-29 February and available shortly thereafter, offered SWPA planners another opportunity to peer over the shoulders of their Japanese adversaries.

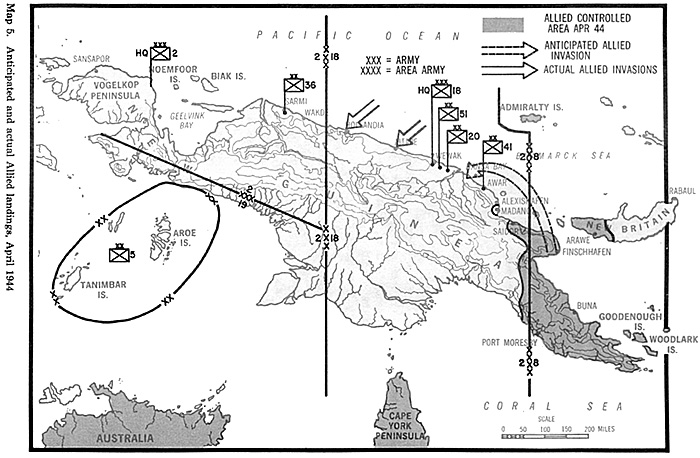

The message formed the core of a staff appreciation of Japanese defensive planning for New Guinea and subsequently appeared in a SWPA G-2 (Intelligence), "Memorandum to the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, (Operations) SWPA." According to the intercepted communications, the Japanese foresaw the next major Allied amphibious operation occurring on the north New Guinea coast between Madang and Awar. Lt. Gen. Adachi Hatazo, commander, Japanese 18th Army, planned to counter such a landing by attacking from the south with his 41st Infantry Division and from the north

with his 20th Infantry Division, thereby "ambushing" any Allied invaders (see map 5). In

fact MacArthur originally had planned to invade the Hansa Bay area. [12]

Then on 5 March 1944, through his chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, he instead proposed to the Joint Chiefs of Staff that two SWPA divisions, supported by the U.S. Pacific Fleet, attack Hollandia on 15 April as a step toward MacArthur's goal of returning to the Philippines. One week later, the JCS approved MacArthur's plan with the understanding that Hollandia could be developed into a heavy bomber base for subsequent air operations against the Palaus and Japanese air bases in western New Guinea and Halmahera. [13]

Hollandia was attractive for SWPA forces because its combination of potential harbor and airfield facilities offered the possibility of a major supply and staging base to launch MacArthur's much heralded return to the Philippines. A leap to Hollandia would bring him 800 kilometers closer to that goal and allow him to bypass the Japanese stronghold at Wewak.

The major drawback to the Hollandia operation was its distance from Allied fighter air bases. Hollandia lay beyond the fighters' effective range, yet SWPA required continuous fighter support for its amphibious landing operation. To carry off the operation, MacArthur needed the carrier-based aircraft, but the Navy was in the midst of preparations for the invasion of the Marianas. Cognizant of the upcoming Saipan operation, and despite his earlier promise of air support for MacArthur, Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, commander in chief, Pacific, refused to allow his carriers to remain in the Hollandia area for the eight-day period MacArthur wanted. Instead, Nimitz offered his naval air arm for the first three days after the initial Army landings. Thus denied sustained naval air support, MacArthur's staff then opted to obtain the vital land-based air support for the Hollandia operation by seizing Aitape, 200 kilometers to the east, where the Japanese had three airfields in various stages of construction and one strip operational.

These fields could serve as the forward bases for Army Air Force fighter

aircraft. Furthermore, U.S. planners reasoned, American troops at Aitape could protect the eastern flank of Hollandia against any westward counteroffensive by the Japanese

18th Army.

As SWPA intelligence officers well knew, 18th Army was moving west. On 13

March a major redisposition of 18th Army appeared in signal traffic. Throughout March,

via Ultra, SWPA followed the painful progress of 18th Army's withdrawal from eastern

New Guinea. As the Japanese pushed westward, MacArthur responded by organizing

Persecution Task Force for the purpose of establishing an airbase at Aitape to support

the Hollandia landings and to serve as a blocking force against the approaching Japanese

forces. In order to confuse the Japanese about MacArthur's objective, SWPA G-2

developed and executed a classic deception operation designed to convince the Japanese

that the main targets of the Allied invasion forces were indeed Hansa Bay and Wewak.

As part of the deception effort, 5th Air Force intensified its attacks against

Madang and Wewak, and dummy parachutes were dropped in the Hansa Bay area.

Increased and conspicuous reconnaissance flights were sent on mapping and

photographic missions over Hansa Bay, and the Navy

was directed to make suitable demonstrations along the coast. SWPA ordered PT boats

to stage isolated operations in Hansa Bay, and empty rubber landing boats, indicative of

disembarked scouting parties, were spotted along the Hansa Bay shoreline. Ultra

intercepts confirmed that the Japanese had swallowed the bait. So successful was this

deception effort that on 21 April, just one day before the actual Allied landings, the

Japanese still expected the Allied invasion behind their lines to occur between Madang

and Hansa. [14]

Ultra also confirmed to SWPA intelligence analysts that the Japanese accepted

the fact that the Allies intended to occupy Madang and Hansa. The Japanese, however,

had no serious expectation of the Hollandia invasion and anticipated no major Allied

operations before June. In the meantime, signals intelligence, confirmed by aerial

reconnaissance, detected a major Japanese Army Air Force buildup near Hollandia. The

mission of this Japanese 4th Air Army, according to Ultra, was "to break up enemy

operations and landings in the Madang area." Forewarned, MacArthur's 5th Air Force

and U.S. Navy carrier-based aircraft struck first and often. In a series of heavy raids

lasting four days, U.S. airmen crippled 4th Air Army, reducing its effective strength to

almost zero. [15]

In addition, Ultra allowed Allied intelligence analysts to monitor the dispositions

of Japanese ground forces near the invasion areas. An Ultraderived signal revealed that

among the 16,000 Japanese near Hollandia, more than 7,600 were Army Air Force

personnel and that an "overwhelming number" of the remainder were service troops.

Ultra also divulged the weakness of Japanese defenses at Aitape.

On 14 April, for instance, the Magic Summary-Japanese Army Supplement

(MSJAS) Summary reported that "at Aitape only two guns were available for AAA

defense" and that timalaria was rampant" in the area. There is little doubt that Ultra's

contribution at the operational level of the Hollandia-Aitape campaign was significant,

but without SWPA's skillful and imaginative planning and use of the intelligence

information, it might have died aborning. Moreover, the employment of Ultra intelligence

before and during the Aitape campaign was regarded by SWPA G-2 and MIS-in a rare

moment of agreement-as a classic application of special intelligence to combat

operations. Such an assessment on the strategic and operational levels was justified; on

the tactical level, it proved an oversimplification.

*Headquarters, Central Bureau, followed MacArthur from Melbourne to Brisbane (September 1942), to Hollandia (late summer 1944), to Leyte (October 1944), to San Miguel (May 1945), and to Tokyo (September 1945) and was deactivated in November 1945.

Chapter 1: Ultra and Pacific Strategy

Back to Table of Contents -- Leavenworth Papers # 9

Back to Leavenworth Papers List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2005 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com