IV. TACTICS AND BEHAVIOR OF THE ITALIAN TROOPS DURING THE INVASION OF RUSSIA

For reasons I am unable to explain Italian sources paid but little attention to the tactics employed by the troops of the Kingdom of Italy throughout the Russian campaign. Only tentative conjectures can therefore be made on the basis of the scant available evidence.

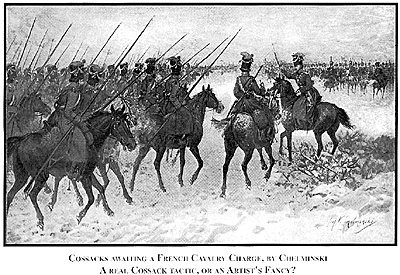

Although not Italian cavalry, it shows Cossacks awaiting a French charge. By Chelminski. A real Cossack tactics or an artist's fancy?

As far as Italian infantry units are concerned, my guess is that in 1812 they never deployed and fought in line. Apart from some skirmishes, the Italian infantry never encountered its Russian counterpart before MaloJaroslavets. At Malo-Jaroslavets an unfavorable terrain pattern made it impossible for the Italians to deploy in line. To approach the town from the Louza valley they had to climb up a steep and broken ravine under heavy artillery and musket fire from the ridge: it is therefore likely that they formed into columns. My conjecture is supported by two quotations from De Laugier's memoirs. He wrote that at the beginning of the battle, as it moved forward to relieve Delzons', Pino's division "advanced silently in closed columns ", later on, Colonel Peraldi of the Guard Conscripts "rallied Pino's second brigade and his chasseurs, formed them in column and ( ... ) led them forward again against the overwhelming Russian masses". [1]

According to Pisani, [2] Pino's division used columnar formations to attack Russian infantry and artillery at Viazma on November 3rd. De Laugier reported that on the same day the Italian Guard infantry advanced in (probably closed) columns against Miloradovich's vanguard cavalry. [3]

In the two major (Viazma and Krasnoe) and in the several minor engagements that followed MaloJaroslavets, the retreating IV Corps had often to face a superior Russian cavalry, Cossacks and regulars as well. Forming square consequently became a common practice for the Italian infantry. Often obliged to repulse cavalry raids when on the move, the Italians probably acquired a certain skill at quickly changing from march column to square and vice versa.

For instance, on November 1st a Cossack pulk caught an Italian column of infantry, artillery and train trudging in the Tsarevo defile. Pisani described the action in his memoirs as follows:

"A raid of Cossacks from Miloradovich's advance guard debouched from our left and disordered the equipages. Many drivers fled, abandoning their wagons ( ... ) until the arrival of the 2nd Light reestablished the situation. Spotting this regiment advancing in square, the assailants withdrew: the order of march was quickly restored". [1]

Excluding Del Fante's desperate attempt on November 16th to break through the Russian line and reach Krasnoe with a small squad of troops formed in square my sources do not mention any case of an Italian square being broken throughout the campaign. It should, however, be said that Cossack swarms were never particularly eager to assault solid squares. A typical defensive formation, the square was also sometimes used with aggressive purposes. Beside the alleged Guard infantry advance at Borodino, this apparently occurred in front of the village of Dukhowcthina on November 10th, the day after the disastrous crossing of the Vop River. The small town, where Eugene intended to rest his depleted troops, was occupied by Russian troops. As Pisani wrote:

"The Viceroy ordered the Guard to attack in echeloned regiment squares. It was then that we spotted the strong Ilowaiskoi(?) cavalry deployed in front of the town. Relying on Platov advancing on our rear, they had planned to encircle us; but the Guard squares rushed forward so dashingly that they succeeded in seizing the town with only few losses. In the meantime the 14th division repulsed the Cossacks". [5]

Russian Colonel Bouturlin did confirm this episode.

There is also some evidence that the Italian light infantry had a good training in advance guard skirmish combat and that in some circumstances they displayed an adequate level of coordination with the Italian light cavalry. Some light companies from Pino's division, for instance, are reported by Cappello to cooperate under artillery fire with French light troops in assuring the fording of the Loutchesa (Lucizza) River on July 27th. The following day at Agaponovchtchina Eugene sent some cavalry together with the 4/1 st Italian Light to relieve Murat's advance guard which had been ambushed. The success of Velij on August 6th came from a fruitful collaboration between the 2nd Chasseurs and three light companies of the Dalmatian Regiment: the latter ambushed a swarm of Cossack that was pursuing a squadron of Chasseurs acting as a bait. The over confident Cossacks had over 60 losses from musket volleys at close range. Viazma was another good day for Italian skirmishers. According to Pisani:

"Emerging from a copse, some Italian light troops almost succeeded in seizing the battery on the center, which fled at full gallop.( ... )the enemy cavalry advanced to out flank our wings, but the Bavarian cavalry, together with our Chasseurs, bravely resisted. Finally, swarms of voltigeurs hidden in the bushes forced the Russians to retire with their accurate fire." [6]

The two chasseur regiments forming the Italian light cavalry brigade and the Queen's Dragoons attached to the Royal Guard had apparently good performances against both infantry and cavalry. It should, however, be stressed that they rarely encountered first class Russian units. Little can be extracted from Italian sources about cavalry tactics and formations. When attacking a long supply convoy and its escort, Queen's Dragoons' Colonel Narboni is said to have released only a squadron, keeping the rest of the regiment in reserve. At Velij the chasseurs are reported to have delivered five consecutive charges before breaking a hollow square formed by escorting infantry with dozens of supply wagons in the center. On September 2nd the 3rd Chasseurs showed coolness and discipline in a difficult situation against Platov's Cossacks. The Italian cavalry were marching ahead of the IV Corps, the chasseurs forming the first ranks followed by the Queen's Dragoons. Spotting several sotnies of Cossacks debouching from a forest:

"Colonel Gasparinetti ordered the 3nd Chasseur forward to attack the enemy. They took a full gallop pace from long distance but were soon disordered by the marshy terrain. In the meantime Platov advanced speedily at the head of a screaming mass of Cossacks armed with lances. Colonel Gasparinetti, seeing his troops disordered, with the greatest coolness ordered to slacken the pace to a complete stop. His squadrons could then quickly reform. After resuming the gallop, the Italians finally delivered the charge." [7]

This episode seems to confirm the good reputation for discipline and military skills the Italian cavalry had acquired in the former campaigns.

According to eyewitness accounts, the Italian artillery ranked high for tactical flexibility, coolness and discipline under fire. At Borodino the Italian guns were in the grand-battery firing on the Raevsky redoubt.

Upon realizing the threat from the Russian cavalry on his left, Eugene rapidly dispatched a battery half-section to cover Delzons' retreating squares. Although isolated and without infantry support at hand, the artillerymen serving these guns did not flee against the approaching cavalry and kept on opening holes in the enemy ranks. They were about to be sabred, when some infantry (French or Italian? see chapter 3) and the reformed IV Corps cavalry came to their relief At Malo-Jaroslavets the Italian artillery opened a bottom upwards fire against Russian batteries on a dominating ridge and succeeded in silencing at least one. Later on, in order to bring the guns in position to support Pino's division they had to push them over a steep ravine and into the narrow streets of Malo-Jaroslavets .

It is a firmly established fact that very high levels of strategic consumption were among the major causes of Napoleon's failure in Russia. Losses due to strategic consumption severely mauled any corps of the Grande Armee engaged in Russia. The units belonging to Napoleon's main body directed to Moscow, Eugene's included, suffered more than those engaged in other sectors.

From the available information on strategic consumption suffered by the Italian contingent some tentative conclusions can be drawn:

Like any other army based on conscription, the army of the Kingdom of Italy was plagued by high rates of desertion throughout the Napoleonic Wars. Line regiments had relatively higher rates than elite regiments. While on the move from Italy to Germany, Pino's division had 382 deserters: 165 from February 15th to March 1st, 118 from March 1st to March 15th, 40 from March 15th to April 1st, 36 from April 1st to April 10th, 23 from April 10th to April 25th. A frequent practice in homeland, desertion tended to decrease when troops were on campaign in countries far from home.

On March 1st at Brixen General Pino had under his command 13,787 men (Villata's brigade included). Losses in the following six weeks amounted to 775 men and 225 horses.This rather high rate of strategic consumption before the beginning of the campaign was mainly caused by bad road conditions and insufficient food and forage supply. On April 3rd Pino's adjutant commandant wrote to the Minister of War:

"After Donauworth our Division marched on miserable roads. Particularly, I had never seen before roads as bad as those stretching between Cronach and Nordhalm, Lobenstein and 1hrlaite. ( ... ) impassable tracks, with mud rising to horse bellies, are expected after Altemburg ( ... ) due to poor harvests in Saxony, horses have only eight pounds of hay." [8]

After the crossing of the Niemen River, when horses died like flies in a terrible thunderstorm, things got worse and worse for Pino's soldiers. Although the 15th division did not participate in any major engagement of the first part of the campaign, upon the arrival in Moscow forced marches, bad roads, marshes, scorched earth, shortage of food and different kinds of diseases had cut the strength of the division down to 4,000 men.

The fate of the other line units was not much better than Pino's. Cavalry regiments suffered terribly for shortage of forage and horses. Since June local remounts were used, but these proved inadequate for efficient military use. Throughout the campaign the Italian cavalry, though successful on the battlefield, had to spare their meagre horses and were rarely in a fit state to adequately pursue the retreating enemy. At Malo-Jaroslavets many squadrons of dragoons had to fight dismounted.

Strategical consumption was a major problem also for artillery. On May 16th at Grogan Lieutenant Pisani, belonging to the artillery park of the IV Corps noted in his diary: "We no longer received regular food supplies and, consequently, could not follow our march schedule." [9]

An interesting instance of losses due to early strategic consumption, was the loss of Pisani's 19pdrs battery. It was left behind because of shortage of adequate draft horses since the beginning of June; it therefore did not

"despite long marches and hard sufferings, the Grenadier Regiment is still steady ( ... ); if the situation of the other two regiments is not as good, this is due to the different fibre of their soldiers, mostly young conscripts. Yet I have the pleasure to inform Your Excellency that, compared with many other units in the army, these regiments are still really good looking"."

The army returns as recorded some days before leaving Moscow 12 clearly show that the IV Corps was still in relatively good shape and this accounts for the demanding assignments it had to meet during the retreat (advance guard before Malo-Jaroslavets, first support to the advance guard after the battle).

After Malo-Jaroslavets, Italian losses due to strategic consumption were no longer recorded. Eyewitness accounts said that, although reduced to few hundreds (about 600 before the Berezina), the Royal Italian Guard, together with the Imperial Guard and a few other elite units of Napoleon's main body, managed to keep a reasonable degree of order, discipline and combat effectiveness until the very last phases of the disastrous retreat.

According to a report from Heilsberg dated December 24th, only 233 Italian soldiers had survived (130 in the Royal Guard). Later reports raised the figures to about 1,000.

A final note, none of the Italian infantry regimental flags (and Eagles) of the IV Corps fell in Russian hands, which tells a lot on the degree of military honor displayed by the Italian contingent. Beside fanions and the like, the only trophy captured during the Campaign is take part in the first phase of the campaign and was able to rejoin the main body only after Borodino.

The veterans of the Royal Guard endured the inconveniences of the campaign with stubborn composure and decidedly better results. On July 1st the effectives of the division amounted to 5,862 men (including 67 detached and 12 reported sick) and 2,077 horses. Three months later in Moscow 4,348 men were still present, 343 reported sick, 444 detached or at the deposits, 15 prisoners of war, 520 stragglers. [10] The Italian Guard strength had been reduced by 25%, less than any grand-tactical unit arrived in the Russian capital, the Imperial Guard included. In a letter to the Minister of War accompanying the October returns General Lechi wrote:

"despite long and hard sufferings, the Grenadier Regiment is still steady; if the situation of the other two regiments is not as good, this is due to the different fibre of their soldiers, mostly young conscripts. Yet I have the pleasure to inform your Excellency that, compared with many other units in the army, these regiments are still really good looking." [11]

The army returns as recorded some days before leaving Moscow [12] clearly show that the IV Corps was still in relatively good shape and this accounts for the demanding assignments it had to meet during the retreat (advance guard before Malo-Jaroslavets, first support to the advance guard after the battle).

After Malo-Jaroslavets, Italian losses due to strategic consumption were no longer recorded. Eyewitness accounts said that, although reduced to a few hundreds (about 600 before the Berezina), the Royal Italian Guard, together with the Imperial Guard and a few other elite units of Napoleon's main body, managed to keeep a reasonable degree of order, discipline, and combat effectiveness until the very last phases of the disastrous retreat.

According to a report from Heilsberg dated Dec. 24, only 233 Italian soldiers had survived (130 in the Royal Guard). Later reports raised the figure to about 1,000.

A final note. None of the Italian infantry regimental flags and Eagles of the IV Corps fell into Russian hands, which tells a lot on the degree of military honor displayed by the Italian contingent. Besides fanions and the like, the only trophy captured during the Campaign was the flag of the Dragoons of the Queen captured at Krasnoe.

[1] De Laugier, op,cit. p. 106

More Neither Caesar Nor Punchinello Army of Italy in Russia 1812 Part I

1) strategic consumption started depleting the Italian contingent very early in the campaign, long before the crossing of the Niemen River;

2) Pino's division had comparatively more losses due to strategic consumption than any other Italian formation in the IV Corps;

3) the Royal Italian Guard arrived in Moscow having suffered only few losses and its general condition and fitness were as good as the Imperial Guards;

4) During the retreat from Moscow the Italian contingent kept a fairly good degree of order and military stance; consequently, they are likely to have suffered comparatively less from strategic consumption than other formations.Sources

Cappello, G., Gli Italiani in Russia nel 1812, CittA di Castello, 1912 (reprinted by Tuttostoria, Parma, 1993)

Chandler, D., The Campaigns of Napoleon, McMillan, London,1966

De Laugier, C., Gli Italiani in Russia, Milano, 1826 (reprint by G.Bedeschi,ed., Mursia, Milano, 1980)

De Rossi, E. "It reggimento italiano di cavalleria 1 Ussari cisalpino poi Dragoni delta Regina dal 1798 at 1814" in Memorie Storico Military, IV, 1910

Regnault, General Jean, Les Aigles Imperiales, 1804-1805, Peyronnet, Paris, 1967.

Nafziger, G., Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, Presidio, Novato, 1988

Pisani, F., Con Napoleone nella campagna di Russia, edited by C.Zaghi, Milano, 1942

Riehn, R., 1812: Napoleon's Russian Campaign, J.Willey & Sons, New York, 1991

Zanoli, A., Sulla milizia cisalpino-italiana. Cenni storicostatistici dal 1790 al 1814, Milano, 1845

Notes

[2] Pisani, op.cit., p.205

[3] De Laugier, op.cit., p. 117

[4] Pisani, op.cit., p.201

[5] Ibid, p.223

[6] Ibid, p.205

[7] De Rossi, Il reggimento italiano di cavallera lo ussari cisalpino poi Dragoni della Regina 1798 al 1814, p. 54.

[8] Cart.2691, Milan Sate Archives, also Capello, op.cit.,

p.412

[9] Pisani, op.cit., p.101

[10] Losses suffered by the Guard at Borodino (about 50 men) are probably included in these figures.

[11] Cart.38, Milan State Archives, also Capello, op.cit., p.385

[12] De Laugier (op.cit., p.98) states that in October 10 the IV Corps could field 23,963 infantry and 1,661 cavalry. This means that since the beginning of the campaign it had lost 39% of its effectives. If my data are correct. apart from the Imperial Guard that was about in the same situation, the others Corps had suffered more than Eugene's (I Corps, 58%); III Corps, (72%); V Corps, (85%).

Introduction

Italian Strategic Role in the Campaign

Behaviour of Italian Troops in Battle: July-October 1812

Behaviour of Italian Troops in Battle: October-November 1812

Large Map of Battle of Malo-Jaroslavets: Oct 24, 1812 (slow: 121K)

Jumbo Map of Battle of Malo-Jaroslavets: Oct 24, 1812 (monstrously slow: 636K

Back to Empire, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents Vol. 2 No. 6

Back to EEL List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by Emperor's Headquarters

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com