The Events of the Second Day

On 16 June, Napoleon, who had spent the night in Charleroi, mounted his horse at dawn. He had meditated upon his plan during the night. He would go first with his right wing toward Sombreffe to assure himself that the road Namur-Nivelles was free of Prussians. Then, Grouchy would be given the task to cover his right, and with the reserve, the Emperor would join Ney in Quatre-Bras. From there, he would move quickly to Brussels by a night march, which would be taken by surprise in the morning. Consequently, there was no need to hurry!

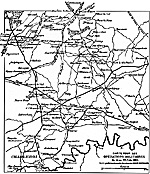

Large Operations Militaires Map (slow download: 143K) or Jumbo Operations Militaires Map (very slow: 280K)

These plans were transformed by Soult into formal orders, [4] but by 9 a.m. none of the generals had yet received them. The troops could not understand why they remained immobile. Everyone knew that every inactive hour was an hour gained by the enemy.

Napoleon's comfortable illusion was quickly disturbed. At 6:30 a.m., according to Pajol, a message sent by Grouchy informed Napoleon that numerous Prussian columns, apparently coming from the east, were concentrating around St. Amand, Brye and the surrounding villages. That message was confirmed an hour later but the Emperor did not change any of his dispositions. He considered these movements as rear-guard movements to deceive the French. Consequently, he confirmed the orders to Ney and Grouchy. What follows is of the utmost importance to understanding Napoleon's thinking about what took place at Ligny and Quatre-Bras. He wrote to Ney:

Orders

"My cousin, ... I am sending Marshal Grouchy with the III and IV Corps to Sombreffe. My Guard will be in Fleurus and my person will be there before noon. From there, I'll attack the enemy if I encounter them and I'll reconnoiter to Gembloux. According to the events, I'll make my decision, perhaps around 3 p.m., perhaps this evening. My intention is that, immediately after I make my decision, you'll be ready to march to Brussels; I'll support you with my Guard, which shall be in Fleurus and in Sombreffe. I desire to arrive at Brussels tomorrow morning. You'll march tonight. . .so you can march three to four leagues [12 to 16 kilometers or 7 to 10 miles] to be in Brussels tomorrow morning at 7 a.m.

"You shall deploy your troops as follows. First Division two leagues in front of Quatre-Bras [8 kilometers, about 5 miles] if there are no problems; six infantry Divisions around QuatreBras and one in Marbais, so I can order it to move toward me, if I need its assistance: it would not slow down your forward march; the Corps of the Count of Valmy [Kellerman] [5]] who has 3,000 elite cuirassiers at the Roman crossroad to Brussels, so I can order it to move toward me, if I need its assistance: as soon as I have made my decision, you'll order it to join you. I wish to have with me the Guard cavalry Division that is commanded by General Lefébvre-Desnouëttes, and I send you the twoDivisions under the Count of Valmy to replace it. But in my present thinking, I prefer to locate him where I could easily call him toward me, if I need his assistance, and to not order Lefébvre-Desnouëttes to make marches and countermarches. However, cover Lefébvre-Desnouëttes with the two cavalry Divisions of d'Erlon and Reille, so we avoid tiring the Guard, because if there are some skirmishes with the English it's preferable to involve the line rather than the Guard.

"I have opted as a general principle during the campaign to divide my army into two wings and a reserve. Your wing shall include the four Divisions of the I Corps, the four Divisions of the II Corps, two Light Cavalry Divisions, and the two Divisions of the Count of Valmy. That should be about 45,000 to 50,000 men.

"Marshal Grouchy shall have about the same strength and will be commanding the right wing. The Guard will be the reserve, and I'll go to the right or the left depending on the circumstances. According to the circumstances, I shall weaken one or the other wing to increase my reserve.

"You understand the importance of occupying Brussels promptly. . .Such a rapid move should cut off the British army from Mons and Ostend.

"I want your dispositions to be well organized, so as soon as you receive the order, your eight Divisions can move quickly and without confusion to Brussels."

Confusing State of Affairs

It was a rather confusing state of affairs. Ney had not, as Napoleon told him, 45,000 to 50,000 men but only six Divisions or about 35,000 men. In fact, he never had that many under his direct control. Furthermore, he could not use Lefébvre-Desnouëttes (i.e., the Guard Lancers). All these ambiguities and contradictions resulted from the fact that Napoleon had to do battle on two fronts and to prepare simultaneously two operations:

The orders to Grouchy were less complex.

Thus, on the morning of the 16th, the situation in Napoleon's mind was as follows. In the west, on his left, no enemy troops were in close proximity. He imagined that the bulk ofthe Anglo-Allied army was beyond the road to Nivelles, needing one more day to concentrate. Hebelieved thathe would be in Brussels before the Anglo-Allies would be in any shape for combat.

Around Quatre-Bras, one could see a few enemy battalions (Napoleon called it poussiére de bataillons, which could be translated as "dust of battalions") incapable of seriously opposing Ney's forward movement toward Brussels, but that was about it. In the center and on the right, the Prussian vanguard, pushed back yesterday, obviously would continue to retreat from Sombreffe to Gembloux and then toward Liege, leaving behind them no more than a corps as a rearguard.

From Napoleon's dispositions, it is clear that he did not expect any serious opposition from either Blücher or Wellington. He had absolutely no conception of impending battle. He spoke of reconnoitering both positions, and occupying them. That was a gross underestimation of his enemies' intents and capabilities!

We know that what took place on the Allied side was altogether different from Napoleon's expectations. Wellington concentrated at Quatre-Bras and Blücher at Ligny. Both had decided to fight, and Wellington had pledged to come to Blücher's aid if possible.

At 10 a.m., additional reports reached Napoleon stating that numerous enemy masses were concentrating in the direction of Quatre-Bras. But the Emperor continued to deny that possibility. He immediately notified Soult and Ney to disregard such reports adding: "Concentrate the Corps of Reille and d'Erlon and that of the Count of Valmy, that is moving at this very moment to join you; with these forces you must combat and destroy all the enemy Corps that can face you. Blücher was yesterday in Namur and it is very unlikely that he has sent some troops toward Quatre-Bras. Consequently, you have in front of you only forces coming from Brussels."

But according to the Emperor's detailed orders, Ney could concentrate Kellermann's cavalry along with the I and II Corps only after the Emperor had reached a decision on what to do. Napoleon realized the contradiction and ordered Lobau to hold the VI Corps temporarily at Charleroi, eventually to reinforce Ney.

Delays

The IV Corps had been delayed and Grouchy was reticent to move forward becauseof the numerous Prussians that occupied the heights to the north and north-east. Napoleon was surprised to find Grouchy still there. He still did not believe there was a significant Prussian concentration. In order to find out for himself, he rode to the outposts of the III Corps and ordered an observatory built on the Naveau Mill. From there, he finally had no choice but to conclude that the Prussians were indeed concentrating, but, in his opinion, like on the previous day, Grouchy overestimated their number. Most certainly, thought the Emperor, all that did not exceed a single Corps - exactly what he had anticipated! [6]

He was partially right, and only for a short while. At that moment, he faced only Zieten's Corps. [7] Meanwhile, Wellington, with General Müffling, was meeting with Blücher, Gneisenau and Grolmann on the heights of Brye at the locality called Moulin de Bussy (the Bussy Mill) which was about 4,000 yards from Napoleon's observatory.

At about 2 p.m., Reille's 1st Division arrived on the east side of Fleurus. From the Brye Mill, one could see the French army, up to that time facing Sombreffe, making a change of front, the right ahead, which indicated that it intended to attack by Ligny and St. Amand. Napoleon now decided to crush the enemy by taking him by a strategic envelopment. Thus, he asked Soult to send Ney the following dispatch:

To Ney

"In front of Fleurus, 16 June, at 2 p.m. "The Emperor ordered me to inform you that the enemy has concentrated some troops between Sombreffe and Brye, and that at 2:30, Marshal Grouchy with the III and IV Corps will attack them.

"The intention of the Emperor is that you also attack what is in front of you, and after that you shall vigorously swing your front in order to contribute to envelop the enemy corps mentioned above. If that Corps was defeated beforehand his Majesty will order to maneuver in your direction to hurry up your operations.

"Inform immediately the Emperor of your dispositions and of what is taking place on your side. "

The above is an excerpt from Soult's register. It shows very clearly that at 2 p.m., Napoleon still had the impression that he faced a single Prussian Corps. In addition, he thought they could be easily driven off. Reality soon set in, however, bringing an entirely different military picture.

We do not intend to cover here the Battles of Quatre-Bras or Ligny but rather the implications of the orders based on Napoleon's faulty assumptions.

Ney's command attacked at about 2 p.m. He has been criticized, probably justly, for failing to attack the key crossroads of Quatre-Bras earlier, before Wellington had time to bring up even more troops.

At Ligny, Napoleon had to take additional time deploying his troops. Simultaneously, the Prussians also had time to deploy their II and III Corps beside Zieten's I Corps. The movements of these Prussian masses had finally convinced the Emperor that he was now facing the bulk of Blücher's army. The French deployment was somewhat slower than Napoleon had anticipated. The three cannon shots that were the agreed signal for the French to start their attack finally sounded at around 3 p.m.

Another Order

Then, Napoleon ordered Soult to send another dispatch to Ney:

"I have written you, one hour ago, that the Emperor was about to attack the enemy on the position it had taken between the villages of Saint-Amand and Brye. At the present time, the action is well under way. His Majesty has ordered me to tell you that you must maneuver immediately in such a way to envelop the enemy's right and fall energetically on its rear. That army is doomed if you act that way. The fate of France is in your hands. So, do not hesitate one moment to start the movement that the Emperor orders you and move toward the heights of St. Amand and Brye."

From that dispatch, sent at 3.15 p.m., it is obvious that Napoleon had not yet a clue about the strength of Wellington's forces deployed or arriving at Quatre Bras. Finally, Napoleon was about to find out that he had been mistaken all along about Wellington's intentions. A direct report from Lobau, [8] received by Napoleon immediately after the above dispatch was sent to Ney, informed him that 20,000 Anglo-Allies were facing Ney at Quatre-Bras.

This was far from poussiére de bataillons as previously thought by Napoleon. Instead of falling on the vulnerable Prussian right flank, Ney was going to have his hands full trying to contain a growing Anglo-Allied force at Quatre Bras. In Napoleon's mind, Ney had more than enough troops to hold Wellington, and thus the Emperor did not give up the idea of outflanking the Prussian right with part of Ney's command. He simply intended to weaken one wing to reinforce the other.

With that in mind, Napoleon wrote directly to d'Erlon, who at that time was around Gosselies, to stop his movement to Frasnes and detach from Ney's command in order to launch the entire I Corps against Blücher's right flank and rear. [9]

Two ADCs were to carry the dispatch to d'Erlon and Ney. Baudus, one of the ADCs, in his Etudes sur Napoleon says that the Emperor told him: "Inform Ney that in spite of any situations he may find himself, it is absolutely imperative to execute this maneuver and that I don't give much importance on what is taking place today on his wing, and that the entire concern is entirely where I am as I want to finish the Prussian army. As for him, if he cannot do any better, he should just hold the British army." [10]

This second dispatch marks quite a change in Napoleon's intentions. Ney's original order to be ready to dash to Brussels is now abandoned and his new mission is to just hold the Anglo-Allies.

At the same time, Lobau's VI Corps was directed to Fleurus and not to reinforce Ney.

Infantry

However, Ney, acting as per his original orders in Napoleon's first dispatch, committed most of his infantry as more Allied forces were moving against him. He just learned that General Girard's Divison [11] was no longer under his control as well as that the I Corps was also to be removed from his command. It is understandable that Ney was profoundly disturbed [12] by the second dispatch. It is important to realize that at that time Ney was not aware that Napoleon had changed his mind, and:

Ney was to become aware of Napoleon's new orders only after Major Baudus joined him much later. Ney was still acting under the orders of the second dispatch and the second dispatch was very clear. As can be seen above, the purpose of his projected maneuver against the Prussians was no longer to fall on their flank but to annihilate the Prussian army. The Emperor asked him to save France while at the same time the means to do so were being taken away from him! How could Ney not have lost his composure in such a dilemma? He ordered General Deleambre to go after d'Erlon's I Corps and to bring it back.

It has been customary to blame Ney for recalling d'Erlon, but that recall was the result of a series of events in which Napoleon must bear the primary responsibility for living in a world of wishful thinking. [13] Clearly, Napoleon failed to send the necessary cavalry probes to confirm his suppositions on the Anglo-Allied and Prussian armies' exact locations. Consequently, he issued Ney and Grouchy deployment orders that were based on the false assumption that Wellington's and Blücher's forces were far away. Hence, their deployments were erroneous dispositions completely incompatible with the proximity between the Anglo-Allied and Prussian armies. In addition, if Ney had been properly informed that his new mission was simply to hold Wellington, he certainly would not have lost his head at the idea of being unable to show up on the other battlefield at Ligny and perhaps would not have recalled d'Erlon's Corps.

This can all be attributed to the incompetence of Soult's Headquarters: As seen above, Ney was not informed directly of Napoleon's new dispositions until much later and by Major Baudus after Colonel Forbin-Janson failed to do so. [14] Major Baudus was dispatched only fifteen minutes after the second dispatch to Ney but, if he had gone to Frasnes by the shortest route (i.e., by Mellet) instead of by Gosselies, he would have reached Ney only some fifteen minutes after the Marshal had received the second

dispatch. As a result d'Erlon failed to participate in either battle.

At Ligny, Napoleon broke through the Prussian center and nearly routed it, but the Prussian right and left wing were able to disengage in good order.

To change this simple success into a decisive victory, the French should have continued their forward movements with extreme vigor, pursuing the defeated Prussians, preventing them from rallying, increasing the disorder in their retreat, and pushing them back to the east far away from Wellington. Napoleon did none of these things.

Commandant Lachouque in Le secret de Waterloo sums up very well Napoleon's memoirs at St. Helena in saying that the Emperor at that time "estimates the Prussians crushed: 30,000 hors de combat [casualties], and 20,000 scattered" and "that they had their fill." Under these conditions why risk a night pursuit? In fact, Napoleon continued to ignore reality and created some new illusions. While the Prussians had been defeated, they were far from crushed as Napoleon chose to believe.

Napoleon went back to the mobile "Imperial palace" to have supper. He was sure this time, like the preceding day, to have finished once and for all the Prussian army. This perhaps explains his inactivity on that evening.

[5] Kellermann, the son of the Duke of Valmy.

Continued

"Monsieur le Maréchal,

Napoleon's Indecision after Ligny

Footnotes

[6] In his memoirs written on St. Helena, Napoleon claimed that he had estimated the Prussians to number some 80,000 and did not doubt Blücher's presence there, but concluded that the old fox was awaiting his reserves.

[7] Zieten's Corps consisted of four infantry brigades (a Prussian infantry brigade was the organizational equivalent of a French Division) and the cavalry of that Corps.

[8] Lobau, as ordered, was still in Charleroi, but had sent his under-chief-of-staff, Colonel Janin, to Frasnes as requested by Napoleon. Around 2 p.m., he reported that the Anglo-Allies at Quatre-Bras were about 20,000 strong.

[9] Colonel Forbin-Janson was given that dispatch and ordered to inform Ney of the new orders. Forbin-Janson found d'Erlon but failed to inform Ney. Fortunately, a duplicate of the order was sent by another ADC, Major Baudus, who informed d'Erlon as well as Ney.

[10] Quoted by Margerit, p. 271. and also Houssaye in 1815.

[11] Girard's Division was part of d'Erlon's Corps and was transferred to Vandamme's Corps.

[12] Pontecoulant in his Souvenirs Militaires reports that Ney said: "That news was a terrible blow for me." (The French text reads: "Le coup que me porta cette nouvelle fut terrible.")

[13] Once more, we have to point out that Napoleon didn't believe that he was facing the entire Prussian army until around 3:30 p.m., after the battle of Ligny started. He finally accepted the presence of an important Anglo-Allied force at Quatre-Bras at about the same time, when he received Lobau's dispatch from Charleroi.

[14] Forbin-Janson was a newly-promoted "improvised" colonel, who had never served in the field before the Waterloo Campaign. Baudus had been presented to the Emperor as a competent ADC.

To 15 June

17 June: The Tardy Pursuit of Wellington and Blücher

The Orders of 18 June

Conclusion and Sources

Back to Empires, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents #12

Back to Empires, Eagles, & Lions List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by The Emperor's Press

[This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com]