The Military Developments after the Battle of Chateau-Thierry

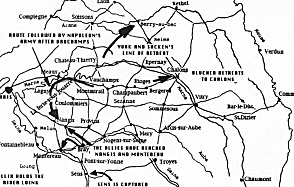

After his victories of Champaubert, Montmirail and Chateau-Thierry, Napoleon's intention was to finish Blucher's command by pursuing him, if necessary, to Chalons. However, on 12 February, even before the end of the Battle of Chateau-Thierry, he had received news that his affairs were not going that well in the south. Schwarzenberg had launched an offensive on the eleventh and had succeeded in driving Marshal Victor's corps back over the Seine. Like Macdonald's failure to seize the bridge at Chateau-Thierry, Victor did not appear to understand the importance of bridges over the Seine in Napoleon's present strategy. For that strategy to be successful, the bridges had to be defended at all costs.

Blucher had received news of Schwarzenberg's successes on the Seine

river at about the same time Napoleon did. He apparently had figured out what

Napoleon's reaction would be. Thus, he changed the withdrawal

orders he had issued on 11-12 February, and marched westward with the Corps of

Kleist and Kapzevitch. His command according to Houssaye (2) included Kleist's Corps (less Klux's Division) 13,500 men, Olssufiev's 1,500 survivors, and

Kapzevitch's Corps, 6,500, plus about 2,000 cavalry. On the 12th, the Prussian

army was at Bergeres, and on the 13th it reached Champaubert easily pushing back

Marmont's small corps.

Unfortunately, that was not the last of the problems the Emperor was to have

with bridges. A strong French garrison still occupied the important town of

Nogent-sur-Seine and guarded its bridge. (1)

A second Allied column had captured Sens on the Yonne river from General

Allix. Victor had ordered the general withdrawal of General Pajol's troops to

Montereau and the destruction of the bridge there, while Allix fell back from the

Yonne to the line of the Loing further to the west. The road to Paris once more

appeared open, and Napoleon at once began to plan the transfer of his troops to

the newly threatened sector, but not until after he had dealt with Blucher in an

imminent encounter.

Unfortunately, that was not the last of the problems the Emperor was to have

with bridges. A strong French garrison still occupied the important town of

Nogent-sur-Seine and guarded its bridge. (1)

A second Allied column had captured Sens on the Yonne river from General

Allix. Victor had ordered the general withdrawal of General Pajol's troops to

Montereau and the destruction of the bridge there, while Allix fell back from the

Yonne to the line of the Loing further to the west. The road to Paris once more

appeared open, and Napoleon at once began to plan the transfer of his troops to

the newly threatened sector, but not until after he had dealt with Blucher in an

imminent encounter.

The Concentration of Forces around Vauchamps

The Concentration of Forces around Vauchamps

At the height of the

engagement, Grouchy's

cavalry crashed into the

Prussian right flank.

Marmont informed Napoleon of

Blucher's movement westward and that he

was forced to give way. But his

withdrawal from Vertus was so well

conducted that he gave Napoleon time to

react. Consequently, on the night of 13-14

February, the entire Imperial Guard was

alerted to proceed to Montmirail under

Marshal Ney, with Friant's First Old Guard

Divison, Meunier's First Voltigeur

Division, Laferriere's 3rd Guard Cavalry,

Guyot's line cavalry, and Drouot's Guard

Artillery. Curial's 2nd Old Guard Division

was to be picked up on the way. In order

for Napoleon to keep contact with

Marshal Mortier's Old Guard, posts were

established every seven and a half miles.(3)

The Battle of Vauchamps

On 14 February, at the time that Napoleon had arrived at Montmirail from

Chateau-Thierry, Blucher's command had passed Champaubert and moved toward

Vauchamps. Napoleon informed Marmont that he was coming to the rescue with the

Guard and General Grouchy's line cavalry. Then he ordered Marmont to attack

Blucher as soon as the Prussians came out of Vauchamps. Marmont skillfully

drew Blucher to attack him on the morning of the 14th to the west

of Vauchamps. Suddenly, to his great surprise, Blucher saw Marmont's weak

force that he had previously been pushing back stop and counterattack vigorously. At the height of the engagement, Grouchy's cavalry crashed into the Prussian right flank.

Charged aggressively, the surprised Prussian vanguard fell back in disorder

into Vauchamps and came out of it in an even more confused condition. (4) Blucher called up his reserves and

prepared his command to eliminate Marmont's weak corps. However,

within the numerous cavalry that deployed opposite him, he recognized

the cavalry of the French Imperial Guard. Blucher realized that serious

trouble was ahead.

At about 9:00 a.m., the cheers of the troops announced the arrival of

Napoleon with the Guard, which formed in columns of attackbehind the

artillery. At a given signal, they stormed Ziethen's 11th Brigade (acting as the

vanguard and then attacked Kleist's Prussian 2nd Corps and Kapzevitch's

10th Infantry Corps. Ziethen's Brigade was badly handled on the spot, but

Blucher succeeded in extricating the rest of his men and commenced his

retreat. During two hours, his troops formed in squares on both sides of the

highway to Chalons, in echiquier (checkerboard), withdrew in good

order, calmly enduring the fire of Drouot's artillery and the repeated

charges of the Guard cavalry. But all was not over yet. Both of Blucher's

flanks were menaced, the right by Grouchy's 3,500 sabers and the left by

Leval-still out of range-and his 7th Division's 4,500 veteran infantry from

Spain along with the cavalry of the Guard.

Blucher, pressed in the front by the French infantry and outflanked on his

right by Grouchy and on his left by the cavalry of the Guard, tried to keep his

harassed command withdrawing in good order. He had managed to do so as far as Janvilliers. But, behind that village, around the wood of Serchamps, he was intercepted and charged on both

flanks by the French cavalry; Blucher lost four guns and 3,000 men. In spite of

these losses, and still full of fight, Blucher managed to rally his forces. He

continued to present a determined front until Drouot, galloping at the head of

50 guns, blasted the Allied troops with canister at short range. But night was

rapidly falling. For two hours, Drouot chased the Prussians as far as

Champaubert, littering the fields and the highway with dead and wounded.

As night arrived, Blucher tried to organize a defense at Champaubert.

Once more Grouchy's cavalry fell on the Prussian flank and scattered them.

At the same time, a charge of the Guard cavalry ordered by Napoleon and Ney

fell on the other Prussian flank with similar success. Both charges broke

through and met in Champaubert. Confusion was everywhere and the

night prevented any further charges.

According to Count de Segur, the night was hiding the extent of the

success. In the midst of the confusion, Blucher, Prince August of Prussia,

Generals Kleist and Kapzevitch were several times on the verge of being

captured, killed or wounded. A brave stand by Ziethen and his artillery ended

the fighting.

Blucher realized that finally the French grip was easing and continued

his retreat as far as Etoges, some ten miles from Champaubert, where,

regaining some control over his troops, he deployed Urusov's 8th Russian

Division. But Marmont, in spite of a pitch black night, had been ordered to

pursue. He managed to attack the Russians in Etoges where he captured 7

guns, 800 men and General Urusov. The rest of that particular Russian

Division melted away into the darkness. Blucher meanwhile continued his

retreat toward Chalons. The time was 7:00 p.m.

The Allies lost 7,000 men, 10 flags

andl 6 guns besides a mass of transport.

Like manybattles ending in a rout, (6) the

losses of the attacker were minimal.

The French ended up losing only 600

men.(7)

Vauchamps, the Aftermath

Blucher was able to rally his troops and withdrew to Chalons to reorganize

his command, under the cover of a Urosov's weak Division at Etoges,

which we have seen was severely handled by Marmont.

Napoleon's intention was to pursue Blucher to Chalons and finish him up.

From there, via Vitry, the Emperor intended to fall on the rear of the

Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia. However, the last dispatches he had

received informed him that the Austro-Russians of the Army of Bohemia had

accelerated their offensive and pushed back Victor and Marshal Oudinot even

further. The Allied vanguards had reached Provins, Nangis, Montereau

and Fontainebleau. Paris was threatened, or more exactly Paris

appeared to be menaced. What Napoleon did not know is that the news

of Blucher's defeats had disturbed the Allied high command. The Allies once

more become very hesitant. One can only imagine what would have

happened if Blucher had been captured at Vauchamps. The invasion of France

might have ended there.

In the face of these developments

what was Napoleon to do? He could

only make a decision from what he

knew! What Napoleon did not know

was that the Allies' forward march was

already halted. These forces received

orders (8) from the alarmed Schwarzenburg to remain in their position and await the development of Napoleon's next maneuvers.

Acting on the suppositions he made

on the battlefield of Vauchamps, the Emperor had developed his plan. To

cover Paris, he had to abandon the pursuit of Blucher. He ordered

Marmont to continue the chase of the Army of Silesia.

That evening, the Guard, minus

Mortier's detachment, slept at

Montmirail, and the next day moved

to Meaux. On 16 February, Napoleon

was at Guignes with his Old Guard

and had his army ready to deal with

Schwarzenberg, leading to events--

Montereau and Craonne -- which form

the next chapter in the 1814 Campaign.

Some additional comments on "The

Six Days Campaign of 1814"

So ended the marvelous episode in

Napoleon's career that is known as "The

Six Days Campaign of 1814." (9) During

these six days, Napoleon had

completely regained his old skill as a

field commander. An author claimed

that during the Campaign of 1814,

Napoleon ceased to be the Emperor and again became the general. There is

a great deal of truth in that. Some authors

have claimed that the second week of

February 1814 is worthy of Napoleon at

his best and compared the tactical

brilliance he displayed during that week

with the great days of the First Italian

Campaign.

He handled his small army

numbering less than 30,000 (10) in a skillful

manner. He was able to coordinate that

small army in a way that was impossible

with the huge armies of the last five

years. In six days his men had covered

-- deep in mud -- some eighty miles,

won four victories and inflicted a

cumulative total of 20,000 casualties, in

addition to capturing a number of guns

and a huge amount of supply wagons.

All this at a relatively small cost in

casualties, with one major difference:

The Allies could replace their casualties

easily while Napoleon in 1814 could

not! That was especially true for the

Guard.

To put matters in their proper perspective, let us quote a footnote from

Houssaye's 1814, p. 69:

"German historians have tried to belittle the credit of these tidy victories

by saying that the French fought two against one. To substantiate their claim

they arbitrarily decrease the allies effectives and inflate those of the

Emperor. However, in taking into account the official returns {Archives

Guerres, JAL} and the numbers reported by foreign reports concerning

the Allied units as they crossed the Rhine, we were able to come up with

the following numbers. (It is well understood that we reduce 20% for the

losses of Olssufiev and Sacken for the Battle of Brienne and La Rothiere and

10% for that of Yorck, Kleist and Kapzevitch):

"At Champaubert: Olssufiev's Corps: 4,700. Divisions Ricard and Lagrange:

3,200; 1st Cavalry Corps: 1,500; 2 squadrons of the Imperial Guard: 150.

Total: 4,700 Russians against 4,850 French."

"At Montmirail: Sacken's Corps: 15,700; Pirch's and Horn's brigades

(part of Yorck's Corps) 16 battalions: 7,000. Ricard's Division: 1,200. Guard

(10 battalions) 4,000,Guard Cavalry: 4,200, Guards of Honor 900. Ney's

Divisions, 2,500. Total 22,700 Russians and Prussians against 12,800 French."

"At Vauchamps: Kleist's Corps (less Klux's brigade) 13,500; Olssufiev's

survivors: 1,500; Kapzevitch 6,500. Divisions Ricard and Lagrange: 3,000;

1st and 3rd Cavalry Corps: 3,600; Guard Cavalry (less Colbert's Division): 3,300,

1 Old Guard battalion: 400. Total: Prussians and Russians: 21,500 against

10,300 French."

"It is necessary to remind Blucher's apologists that it was with only 24,000

men -- the elite of his army to be truthful -- that Napoleon had embarked in his

operations against the 57,000 of the Army of Silesia."

In addition, if Napoleon had been better served by his Marshals, it is quite

possible that he would have achieved Blucher's complete destruction if he

not been compelled to turn southward against the Army of Bohemia. That he

was not able to do so is the consequences of two major mistakes from two of his

marshals, namely:

(1) Macdonald's (11) failure to secure

the bridge on the Marne at Chateau-Thierry. If had done so, Yorck's and

Sacken's commands-their line of retreat cut off-most likely would

have been forced to surrender.

(2) Victor's inability to hold the line of the Seine against Schwarzenberg.

Victor was one of Napoleon's commanders who had been demoralized by the massive French

defeat at Leipzig and the subsequent retreat to France. During the 1814

Campaign, Victor had become too lethargic for independent command

and, a few days later, Napoleon had to remove him from the command of his

corps. Such an independent command required the competence of a Davout, a

Soult or even of a Marmont, but certainly not of a demoralized Victor.

Let us say once more that it is quite

possible that the Army of Silesia could

have been completely destroyed, if the Seine front had been held better and/or if only Napoleon had known that Schwarzenberg's army was standing still awaiting for the outcome of the

Emperor's maneuvers. As mentioned above, one can imagine what would

have happened if Blucher had been captured at Vauchamps. The invasion

of France might have ended there.

As a consequence the appearance of Napoleon with the Guard on

Schwarzenberg's rear-with the Army of Silesia eliminated-would have

been enough to force the latter back on his starting line around Troyes or even

force him to retreat to the Rhine. Blucher greatly reduced command would have

had no choice but to do the same....

However, was took place was somewhat different. The Army of

Silesia, although shaken and scattered, was still very much in being. The timely

arrival of reinforcements in the form of the Russian Winzingerode's 30,000

strong corps was to repair much of the damage of the past week's defeats.

Meanwhile, Blucher was reconsolidating his army, including

Sacken's and York's commands, at Chalons. Soon the Army of Silesia was

again operational. Nevertheless, Blucher had been taught a serious

lesson.

Footnotes

(1) Nogent was defended by General

Bourmont's garrison of 1,200 men despite the fact that the town had been set afire

by Austrian howitzers. Bibliography

De Segur, Comte Philippe, Du Rhin a

Fontainebleau, Nelson, Paris, date

unknown. Go to The Battle of Vauchamps: Prussian Account Related:

The able Grouchy (5) found a road

running parallel to the Prussian line of retreat and managed to get ahead of the

hard pressed Allied squares. The Prussians appeared hopelessly trapped.

However, the Prussians were saved by the mud as Grouchy's charges could

not get momentum and were not supported by his horse artillery which,

also because of the mud, had not been able to join him in time. Nevertheless,

his 3,500 cavalrymen broke some squares and threw the Prussian masses

into confusion.

The able Grouchy (5) found a road

running parallel to the Prussian line of retreat and managed to get ahead of the

hard pressed Allied squares. The Prussians appeared hopelessly trapped.

However, the Prussians were saved by the mud as Grouchy's charges could

not get momentum and were not supported by his horse artillery which,

also because of the mud, had not been able to join him in time. Nevertheless,

his 3,500 cavalrymen broke some squares and threw the Prussian masses

into confusion.

(2) Houssaye, 1814, p. 70

(3) Mortier was pursuing Yorck and Sacken

beyond the Marne.

(4) Vauchamps was and still is a small

village devoted to the production of wheat as it was in 1814. It consists of a

main street with houses built on the side of the road. Most of the present day

houses were already there in 1814.

(5) Grouchy was an excellent general. His

name has been unjustly tarnished for his alleged poor role at Waterloo. In fact

he obeyed Napoleon's orders in engaging at Wavre. His skillful

withdrawal after the disaster of Waterloo is a remarkable operation,

which we will cover in a future issue.

(6) Vauchamps may have been only a

partial route.

(7) These figures are from Houssaye, p.

69, who is using a number of sources to substantiate his claim among which

are: Archives Guerres, Vincennes; Marmont's Memoires VI, 56-60,

Muffling, 57-61, Plotho, III, 186-187, Schultz, XII, 132-133.

(8) Orders from Schwarzenberg dated

February 15 and 17, ref. Plotho III, 157-158, 207-211, quoted by Houssaye.

(9) David Chandler, The Campaigns of

Napoleon, p. 975.

(10) Let us not forget that during these

six days, the bulk of his forces were the still highly trained guard and high

quality cavalry and artillery, but he also had some raw recruits that behaved

magnificently like Ricard's command at Montmirail. There is no doubt that

Napoleon being in charge during these battles had a strong inspirational effect

on his troops. In all fairness, there is also little doubt that the prestige of the

"Alt Kaisergard" also played a significant part in defeating the Prussians.

(11) Napoleon's judgement pronounced

at St. Helena was not flattering to Macdonald. He conceded his courage

and loyalty but Napoleon labeled him slow and even lazy, able enough with

a small force up to 20,000 men and under supervision, but no more than

that. The events around Chateau-Thierry appear to confirm that.

Houssaye, 1814, Perrin, Paris, 1888.

Lachouque, Commandant Henri,

translated by Anne S.K. Brown,

Anatomy of Glory, Brown University

Press, 1961.

Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon

Numerous miscelaneous notes from

French Archives (Archives Guerres and

Bibliotheques Nationale).

Mikhailofsky-Danielefsky, A. History of the Campaign of France in the Year 1814,

1992 reprint by Ken Trotman Ltd. Cambridge. England.

Zweguintov, L'Armee Russe, Paris.

Back to The Battle of Vauchamps Introduction

Back to Empires, Eagles, & Lions Table of Contents #11

Back to Empires, Eagles, & Lions List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by The Emperor's Press

[This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com]