Most of Cromwell's life up to the age of forty-one was spent in what is now Cambridgeshire He grew up in Huntingdon sixteen miles Northwest of Cambridge where his father Robert Cromwell farmed the tithes of the nearby parish of Hartford When the time came for him to enter Cambridge University he did not go to his fathers college Queens but to Sidney Sussex a college With a decidedly Protestant character founded in 1596 by the executors of Lady Frances Sidney Countess of Sussex In the statutes of the college it was stipulated that the masters and Fellows must abhor 'popery and all heresies, superstitions and errors.' Except for fee-paying students who were known as Fellow Commoners and Pensioners, all student were required to make their main aim the taking of holy orders.

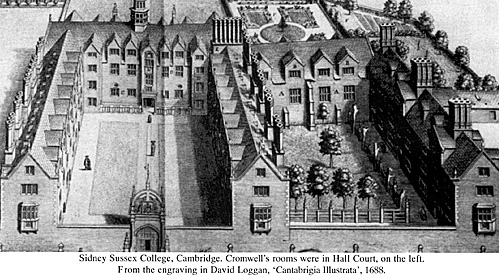

The entry in the college register show that Cromwell became a fellow Commoner on 23 April 1616 two days after his seventeenth birthday. The Master of the college at that time was Dr Samuel Ward a Calinist theologian with a reputation for being a stem disciplinarian Under his guidance both the college rules and the university statutes were rigorously enforced. It would therefore seem likely that if Oliver had been guilty of the riotous behaviour later attributed to him by his enemies, especially certain restoration writers, there would probably have been some record of it. Certainly any peccadilloes of which he may have been guilty appear to have gone undetected, or at least unrecorded, by the college authorities. Apart from the fact that he presented a silver stoup to the college at the time of entry and that he had rooms on the first floor of the north side of Hall Court with a bay window overlooking Sidney Street, nothing is really certain about his life at Sidney Sussex. In any case his sojourn in Cambridge did not last very long. In June 1617 his undergraduate days came to an abrupt end, not through any lack of ability as a scholar, but as a result of the sudden death of his father.

Cromwell first began to come into focus on the Cambridge scene from 1636, when on the death of his uncle Sir Thomas Stowald, he inherited a considerable estate, consisting of land and property in and around Ely. Except for the period from 1628 to 162, when he had been one of the two burgesses representing Huntingdon in the turbulent third Parliament of Charles 1, Cromwell had spent most of the intervening years since leaving Sidney Sussex farming the flat, fertile land of the south-east Midlands, first at Huntingdon then at St Ives. Even before he and his family moved to Ely, he was probably aware of how his uncle had resisted the draining of the Fens in the reign of James I in order to protect the drainage rights, as well as the fishing and fowling, of the poor commoners. In any event he had only been living in Ely for a few months before he became involved in similar dispute.

Throughout the seventeenth century the area of cultivation was gradually being extended to feed the growing population, and it is evident that Cromwell did not object to drainage in general. However, due to his concern for the commoners of Ely, he declared himself to be strongly opposed to the drainage of the fens, especially his own area of fenland known as the Great Level. Besides the drainage companies, the crown was also concerned with the profits to be derived from draining The Fens, and it was not long before the government of Charles I became aware of Cromwell's opposition. They were doubtless already aware of Cromwell, for he had been one of the members of Parliament in 1629 who had refused to adjourn, when commanded to do so by the King, until Sir John Eliot's resolution condemning illegal subsidies and popery had been presented to the Commons. However that may be, clearly Cromwell was not in any way deterred, for in 1638 it was 'commonly reported by the commoners in Ely Fens adjoining that Mr Cromwell of Ely had undertaken, the paying him a groat for every cow they had upon the common, to hold the drainers in suit for five years and in the meantime they should enjoy every foot of their common'.

Of course, at that time the Fens were till a remote and somewhat untamed part of the country, and championing the fenland commoners was hardly a very lofty cause in the eyes of many of Cromwell's contemparies. When his enemies later referred to him as 'Lord of the Fens', the title was awarded only for the purpose of ridicule. However, in retrospect it would appear that they considerably underestimated the significance of Cromwell's fenland activities. It was not only the commoners grazing rights that were endangered by fen drainage. People throughout the area, including in and around Cambridge, were afraid that such drainage might lead to the loss of their inland navigation routes Cromwell's part in the dispute therefore won him many friends, not only in Ely, but further afield in Cambridgeshire. It also reminded his many influential relations, including John Hampden and Oliver St. John, as well as like-minded ex-Parliamentary colleague, of Cromwell's integrity, determination, and obvious ability to command respect. Consequently when Charles I decided early in 1640, owing to his Scottish problems, that it was necessary to summon Parliament, Cromwell was a fairly obvious candidate Since Huntingdon was no longer a possibility, he was invited to stand as one of the two burgesses for the town of Cambridge, and after becoming a freeman by the payment of one penny to the poor, one of the preconditions of candidature, he was duly elected.

More Cromwell and Cambridge

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Although Oliver Cromwell is one of Cambridge's most illustrious sons and one of the best known figures in English history, it would appear that, wheather consciously or otherwise, Cambridge has always tended to neglect his memory. Visitors to Cambridge especially if they come from overseas countries enjoying democratic institutions, may often be surprised to find that apart from a plaque in Sidney Sussex College curtly and vaguely recording the burial of his head, there is no memorial to Cromwell either in the town or in the university. Having seen the statue of Cromwell outside the House of Commons they may well wonder why he is not equally commemorated in Cambridge. He was after all a representative of Cambridge in both the Short and the Long Parliaments and as a military commander was particularly concerned with the security of Cambridge especially during the perilous years from 1642 to 1646 when it was the headquarters of the eastern Association largely as a result of Cromwell ensuring that his constituency was well defended there was neither any fighting in or around Cam-bridge nor any serious damage to buildings Throughout the C Civil War Cambridge was able to live in comparative peace and the university continued to maintain its standard of scholarship.

Although Oliver Cromwell is one of Cambridge's most illustrious sons and one of the best known figures in English history, it would appear that, wheather consciously or otherwise, Cambridge has always tended to neglect his memory. Visitors to Cambridge especially if they come from overseas countries enjoying democratic institutions, may often be surprised to find that apart from a plaque in Sidney Sussex College curtly and vaguely recording the burial of his head, there is no memorial to Cromwell either in the town or in the university. Having seen the statue of Cromwell outside the House of Commons they may well wonder why he is not equally commemorated in Cambridge. He was after all a representative of Cambridge in both the Short and the Long Parliaments and as a military commander was particularly concerned with the security of Cambridge especially during the perilous years from 1642 to 1646 when it was the headquarters of the eastern Association largely as a result of Cromwell ensuring that his constituency was well defended there was neither any fighting in or around Cam-bridge nor any serious damage to buildings Throughout the C Civil War Cambridge was able to live in comparative peace and the university continued to maintain its standard of scholarship.

Introduction

Long Parliament

Destructive Behaviour

Excerpt: Cromwell in Ely

Excerpt: Clarenden, Life

Excerpt: Parliament Orders

Excerpt: Barwick

Back to English Civil War Times No. 56 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com