The Cromwell influence in the Huntingdon area had been gradually shrinking as the estates of Sir Oliver Cromwell had been sold off over time to meet his rising debts. Sir Oliver's investments in the estate of James I had yielded little reward and by 1627 the majority of his holdings including Huntingdon Castle and Hinchingbrooke had been lost to other parties. Of those to gain most from the losses of the Cromwell family was Edward Montague, 1st Earl of Manchester and Lord Privy Seal. His acquisition of a large portion of the Cromwell's influence on the electorate caused considerable friction between Cromwell and Montague that never lessened even when they fought on the same side during the wars. Though allies against the King they argued bitterly over the recruitment of religious independents in the Eastern Association. Robert Bernard, who purchased Huntingdon Castle on behalf of Montague and eventually became MP for Huntingdon in 1640 was harassed so badly by Cromwell that in 1643 he sought the protection of the 2nd Earl of Manchester, Mandeville.

The Cromwell influence in the Huntingdon area had been gradually shrinking as the estates of Sir Oliver Cromwell had been sold off over time to meet his rising debts. Sir Oliver's investments in the estate of James I had yielded little reward and by 1627 the majority of his holdings including Huntingdon Castle and Hinchingbrooke had been lost to other parties. Of those to gain most from the losses of the Cromwell family was Edward Montague, 1st Earl of Manchester and Lord Privy Seal. His acquisition of a large portion of the Cromwell's influence on the electorate caused considerable friction between Cromwell and Montague that never lessened even when they fought on the same side during the wars. Though allies against the King they argued bitterly over the recruitment of religious independents in the Eastern Association. Robert Bernard, who purchased Huntingdon Castle on behalf of Montague and eventually became MP for Huntingdon in 1640 was harassed so badly by Cromwell that in 1643 he sought the protection of the 2nd Earl of Manchester, Mandeville.

The Huntingdon Charter

Adding insult to injury however were events leading to Montague, as Lord Privy Seal, (the most senior position in Parliament), having to put Cromwell in his place for his part in the protest over the Huntingdon Charter.

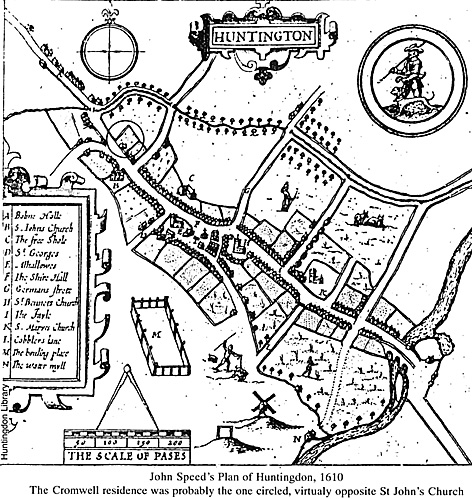

On 15th July 1630 the King issued a new charter for the town of Huntingdon completely altering the structure of the governing of the town. It altered the arrangement from one of open government to a closed corporation of 12 aldermen , a recorder who happened to be the unfortunate Robert Bernard at the time and, selected by these persons, a mayor. Cromwell, along with Thomas Beard and Robert Bernard were made Justices of the Peace, '...to preserve and keep the peace of as, our heirs and successors within the Borough of Huntingdon

This was not as a result of a passing fancy by the King but to settle a dispute that had got seriously out of hand amongst the elite of Huntingdon over the best way to spend a sum of money bequeathed to the town. Cromwell's opponents requested the new charter and made sure Cromwell and his allies were cut out of the new power structure as much as possible.

Cromwell's appointment was given in the hope of placating him but it did more to anger him. So much so that his protests led to a brief stay in custody and the meeting with Montague and the Privy Council for his "disgraceful and unseemly speeches" where he was coerced into making a humiliating apology. His motives were not just on the personal snub but out of sympathy for the poorer tenants of the area as it gave the alderman unlimited control of their property and possessions.

Though bound by duty to punish Cromwell he had some sympathy to the protest and ordered amendments to be made. The following excerpts from a letter by Montague, the Earl of Manchester shows his version of events, with regard to Cromwell:

- "Whereas it pleased your lordships to refer unto me the differences in the town of Huntingdon: about the renovation of their charter, and some wrongs done to Mr Mayor of Huntingdon and Mr Barnard, a counsellor-at-law, by disgraceful and unseemly speeches, used of them by Mr Cromwell of Huntingdon; as also the considerations of divers abuses and oppressions complained of against one Kilborne, post-master of Huntingdon, and Brookes, his man. I have heard the said differences, and do find those supposed fears of prejudice that might be to the said town. by their late altered charter from bailiffs and burgesses to mayor and alderman, are causeless and ill-grounded, and the endeavour und to gain many of the burgesses against this new corporation was very indirect and unfit, and such I could not but much blame them that stirred in it. For Mr Barnard's carriage of the business in advising and obtaining the said charter. it was fair and orderly done, being authorized by common consent of the town to do the same, and the thing effected by him tends much to the good and grace of the town."

"For the words spoken of Mr Mayor and Mr Barnard by Mr Cromwell, as they were ill. so they are acknowledged to be spoken in beat and passion and desired to be forgotten. And I found Mr Cromwell very willing to hold friendship with Mr Barnard, who with a good will remitting the unkind passages past, entertained the same. So I left all parties reconciled and wished them to join hereafter in things that may be for the common good and peace of the town".

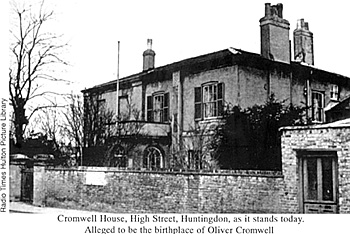

Though Cromwell's actual reaction to the outcome of events is unclear he and his family only lived in Huntingdon for another 6 months. Either out of disgust, despair or the feeling there was little he could do in the town, if his, possibly later, prophecy of greatness was true it was no longer to be realised in Huntingdon. His financial situation was also in a poor state, the inheritance from his father was certainly nothing grand and his annual income was closer to £ 100 than £ 300. He could not even turn to his uncle for assistance, either political or financial, as by this time Sir Oliver had been forced to sell up.

In May 1631 he sold his property and moved to St. Ives where a Cambridge friend, Henry Downhall, was the minister and became a tenant farmer. Some sources state he very nearly emigrated to New England instead. If he had aims to escape the influence of the Earl of Manchester this was not the place to do it. Montague owned the manor court and profited from the market tolls in St. Ives. Though his opinion of this arrangement isn't known he did not hesitate when, on the death of his uncle Sir Thomas Steward in 1636, he inherited lands and property in Ely and moved there immediately.

Cromwell's house in Ely was located near St Mary's Church, (as Thomas Carlyle describes, "two gunshots away from the Cathedral"), and still stands today as the only one of Cromwell's residences in a good state of repair. He inherited his uncles duty as tithe collector for the area and made a living by working some of his lands and subletting the rest. He made additional earnings with other agriculturally based ventures alleged to include brewing and his income rose to a more gentlemanly £ 300 to £ 400 a year. A 1641 tax return suggests he was one of the wealthiest residents of Ely. In a letter sent in 1643 though he had stated, "my estate is little", it didn't prevent him from contributing £ 1,200 towards Parliament's war effort in England and Ireland. His time among the Fens was probably the most peaceful and settled of his life, when compared to other periods. A whimsical poem by Marvell captures the moment perfectly:

Cromwell's house in Ely was located near St Mary's Church, (as Thomas Carlyle describes, "two gunshots away from the Cathedral"), and still stands today as the only one of Cromwell's residences in a good state of repair. He inherited his uncles duty as tithe collector for the area and made a living by working some of his lands and subletting the rest. He made additional earnings with other agriculturally based ventures alleged to include brewing and his income rose to a more gentlemanly £ 300 to £ 400 a year. A 1641 tax return suggests he was one of the wealthiest residents of Ely. In a letter sent in 1643 though he had stated, "my estate is little", it didn't prevent him from contributing £ 1,200 towards Parliament's war effort in England and Ireland. His time among the Fens was probably the most peaceful and settled of his life, when compared to other periods. A whimsical poem by Marvell captures the moment perfectly:

- From his private gardens, where

He lived reserved and austere

As if his highest plot

To plant the bergamot

Warts, and Everything

As other authors have noted his life amongst the Fens and it's people had some influence on his demeanour and appearance. It was not something he worried much about but it was not overlooked by his peers, especially Philip Warwick who saw him making a speech in Parliament and had this to say about him:

'The first time, that ever I took notice of him, was in the very beginning of the Parliament held in November 1640, when I vainly thought my selfe a courtly young Gentleman: (for we Courtiers valued our selves much upon our good cloaths.) I came one morning into the house well clad. and perceived a Gentleman speaking (whom I knew not) very ordinarily apparelled; for it was a plain cloth-sute, wich seemed to have bin made by an ill country-taylor: his linen was plain. and not very clean, and I remember a speck or two of blood upon his little band, which was not much larger than his collar, his hat was with-out a hat-band: his stature was of a good size. his sword stuck close to his side. his countenance swoln and reddish, his voice sharp and untunable. and his eloquence full of fervor: for the subject matter would not bear much of reason; it being in behalf of a servant of Mr. Prynn's, who had disperst libells against the Queen for her dancing and such like innocent and courtly sports: and he aggravated the imprisonment of this man by the Council-Table auto that height. that one would have beleived. the very Goverment it selfe had been in great danget by it.'.

Not that Cromwell would have been particularly offended by this opinion of his image, when commissioned to paint Cromwell's portrait, Ely was told:

'I desire you would use all your skill to paint my picture truly like me, and not flatter me at all, but remark all these roughness, pimples, warts, and everything, otherwise I will never pay a farthing for it.

Most notable of his physical faults was a rather bulbous nose to which at least one quote can be attributed by Sir Arthur Hesilrige who told him "If you prove false. I will never trust a fellow with a big nose again".

Later in life when he became Lord Protector more attention was given to his appearance, he got a better tailor and expanded his wardrobe from dour colours and black to include a musk coloured suit and even one embroidered with gold. This was not lost on Warwick who enthused approval of Cromwell's 'great and majestic deportment and comely presence'.

Despite his unkempt appearance his allies were impressed with his ability to inspire and his resolution in his beliefs. John Hampden corresponding with Lord Digby remarked:

"That slovenly fellow._.who hath no ornament in his speech if we should ever come to have a breach with the King (which God forbid) in such case will be one of the greatest men of England."

Chief of Sinners

It was during the formative years of his political life, between 1628 and 1638 Cromwell went through a profound religious conversion. His health suffered too in this phase of his life as much as his spirit did. A doctors casebook records his 'valde melancholius' in 1628, his flesh was very dry and withered, he had recurring stomach pains for 3 hours after meals and pains down his left side. Though he tried various remedies, none worked and it is likely his illness was as a result of stress. Another remedy he tried was mithridate which may or may not have assisted his resistance to plague but did however clear up his acne.

Sir Philip Warwick, in his Memoires of the Reigne of King Charles I describes, in a rather exaggerated fashion the events of his revelations:

"After the rendition of Oxford, I living some time with the Lady Beadle (my wife's sister) near Huntingdon. had occasion to converse with Mr. Cromwell's Physician. Dr. Simcott, who assured me, that for many years his Patient was a most splenetick man, and had phansyes about the cross in that town; and that he had bin called up to him at midnight and such unseasonable houres very many times. upon a strong phancy, which made him believe he was then dying; and there went a story of him. that in the day-time lying melancholy in his bed. he beleived, that a spirit appeared to him. and told him. that he should be the greatest man (not mentioning the word King) in this kingdom. Which his uncle, Sir Thomas Steward. who left him all the little estate Cromwell had. told him was traitorous to relate. The first years of his manhood were spent in a dissolute course of life. in good fellowship and gaming, which afterwards he seemed very sensible of and sorrowful for and as if it had bin a good spirit, that had guided him therein. he used a good method upon his conversion-. for he declared, he was ready to make restitution unto any man, who would accuse him, or whom he could accuse himselfe to have wronged: (to his honor I speak this, for I think the publick acknowledgements men make of the publick evills they have done. to be the most glorious trophies they can have assigned to them.) When he was thus civilised, he joyned himselfe to men of his own temper. who pretended unto transports and revelations."

His political activities at the time leaned strongly towards a religious content, such as his part in speaking for 'sectaries' which John Hackett in his 'Scinia Reserata', intended for Charles I to read, remarks on. This excerpt displays quite clearly the growing dissent among the Parliamentarian faction and makes reference to Cromwell's future ally Essex and attempts to portray Cromwell as being motivated by bitterness and envy due to his family's losses to the Earl of Manchester.

"I know him, (said the Bishop) at Bugaen he was a common Spokesman for Sectaries, and maintain'd their Part(Pact?) with Stubborness. He never discoursd as if he were pleas'd with your Majesty, and your Great Officers: and indeed he loves none that are more than his Equals. He talks openly, that it is fit that some should act more vigourously against your Forces, and bring your Person into the Power of the Parliament. He saith that Essex is but a half Enemy to your Majesty: and hath done you more Favour than Harm. His Fortunes arc broken. so that he cannot be what he aspires to, but by your Majesty's Bounty, or by the Ruine of us all."

Though there is no firm evidence that Beard specifically was a major influence on Cromwell, (though he shared Beard's habit of referring to god's judgements as 'providences'), the enthusiasm for puritanism and arguments against Anglican reforms were similar enough to be worthy of consideration. Like all Puritan's he had a deep belief in all things being by the will and hand of God and believed all the pomp and ceremony as practiced by the Roman Catholics was blasphemy. They were more concerned with religious doctrine and the Bible's message without all the trappings and traditions introduced by men. They believed strongly that all aspects of their life should have a religious motivation and adopted a sober style of living which they tried their best to impose on their fellow man. Cromwell demonstrated these beliefs using his position and political influence to promote those who preached the Puritan message and conversely trying to influence those who worked against these goals. In his own words:

"Out rest we expect elsewhere this being the cause of God and of his people, so many saints should be in their security and case, and not come out to the work of the Lord in this great day of the Lord".

Under James I's more tolerant rulership, the feelings of the Protestant's were always considered. Charles and William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury influenced by the Dutch theoligan Armenius were keen to establish a more Catholic style of worship.

A letter to a Mr. Storie encouraging him to recompense a Puritan lecturer Dr. Well's for a religious talk he had given shows his fervent belief in the support of the Puritan message.

- "(To my loving Friend Mr. Storie, at the Sign of the Dog in the Royal Exchange, London- Deliver these.)

Mr. Storie,

Among the catalogue of those good works which your fellow citizens and our countrymen have done, this will not be reckoned for the least, that they have provided for the feeding of souls. Building of hospitals provides for men's bodies; to build material temples is judged a work of piety; but they that procure spiritual food, they that build up spiritual temples, they are the men truly charitable, truly pious, Such a work as this was your erecting the lecture in our country: in the which you placed Dr. Welles a man for goodness and industry, and ability to do good every way, not short of any I know in England: and I am persuaded that, sithence his coming, the Lord hath by him wrought much good amongst us.

It only remains now that He who first moved you to this put you forward to the continuance thereof: it was the Lord, therefore to Him lift we up our hearts that He would perfect it. And surely, Mr. Storie, it were a piteous thing to see a lecture fall, in the hands of so many able and godly men as I am persuaded the founders of this are in these times wherein we see they are suppressed, with too much haste and violence by the enemies of God his truth. Far be it that so much guilt should stick to your hands who live in a city so renowned for the clear shining light of the gospel. You know. Mr. Storie to withdraw the pay is to let fall the lecture; for who goeth to warfare at his own cost? I beseech you therefore in the bowels of Christ Jesus put it forward, and let the good man have his pay. The souls of God his children will bless you for it: and so shall I and ever rest.

Your loving friend in the Lord,

OLIVER CROMWELL

St. Ives, 11th of January, 1635

Sensing the turbulent times ahead he was in preparation to 'put forth himself in the cause of his God'. His cousin, Mrs. St. John with whom he was close received a letter from Cromwell, in October 1638, which in a fervently spiritual tone spoke of this sense of duty:

"Yet to honour my God by declaring what He hath done for my soul, in this I am confident, and I will be so. Truly, then, this I find; that He giveth springs in a dry and barren wilderness where no water is, I live (you know where) in Mesheck, which they say signifies Prolonging; in Kedar, which signifieth Blackness: yet the Lord forsaketh me not. Though He do prolong. yet He will (I trust) bring me to His tabernacle, to His resting place. My soul is with the congregation of the first-born, my body rests in hope, and if here I may honour my God either by doing or by suffering, I shall be most glad.

Truly no poor creature hath more cause to put forth himself in the cause of his God than I. I have had plentiful wages beforehand, and I am sure I shall never earn the least mite. The Lord accept me in his Son, and give me to walk in the light, and give us to walk in the light, as He is the light. He it is that enlightened our blackness, our darkness. I dare not say, He hideth His face from me. He giveth me to see light in His light. One beam in a dark place hath exceeding much refreshment in it. Blessed be His name for shining upon so dark a heart is mine! You know what my manner of life hath been. Oh, I lived in and loved darkness. and hated the light. I was a chief, the chief of sinners. This is true; I hated godliness, yet God had a mercy on me. Oh the riches of His mercy! Praise Him for me, pray for me, that He who hath begun a good work would perfect it to the day of Christ".

It was Cromwell's belief in God's will that guided his actions more than anything. His inaction at certain times was likely as a result of waiting to see the best course of action, "waiting upon the Lord, and not knowing what course to take, for indeed we know nothing but what God pleaseth to teach us of His great mercy".

More Birth of Cromwell

Back to English Civil War Times No. 56 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com