By early January 1645 Grenville's army was approaching its intended strength of 6000 men. Besides the "New Cornish Tertia", he also had the support of various Trained Band units and "volunteer" regiments. The Cornish Trained Bands seem to have stuck to their usual practice of refusing to serve East of the Tamar, and were of little use in any direct assault on Plymouth. Of slightly more value were the Devon units serving with Grenville, though the distinction between Trained Band and "volunteer" is not always clear. They included among others Sir William Courtney's Foot and Prince Maurice's Foot, under LieutenantColonel Phillip Champeron. In all, Grenville probably had about 5000 foot, 2000 of them in the "New Cornish Tertia". His horse were about 1000 strong, including his own and Sir Thomas Hele's Regiments, and he also had an artillery train of uncertain size.

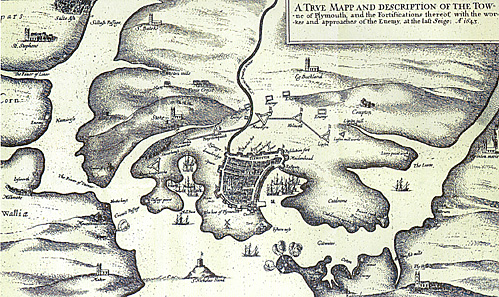

The main strength of Plymouth's defences consisted of a system of outworks occupying the high ground which overlooked the town on its northern side. It consisted of the usual earthen ramparts linking a series of forts or scones, of which the most important running east to west, were Lipson, Holiwell, Maudlyn, Little Penny-come-quick, Pennycome-quick and the Newwork Forts. If Grenville could breach this line he would be in a position to bombard the town below, whose further defence would be rendered difficult if not impossible.

The Royalists commenced operations on 8 January, and during the next two days, despite being hindered by heavy rain, gradually extended their siege lines forward from the Royalist strongpoint of Penny Cross Hill Fort. On the night of 10/11 January Grenville launched a major assault directed against Maudlyn and both Penny-come-quick Forts. Grenville's men seem to have advanced in three bodies. In front came a tertia about 2000 strong, formed from the "New Cornish Tertia". It was supported by two other brigades, each of 1500 men, consisting of Trained Band and other volunteer units.

At Maudlyn the defenders stood firm long enough for the sound of firing to alert Colonel John Birch, whose Regiment was evidently on duty that night. At about 2 a.m., Birch set off to the assistance of the Maudlyn garrison at the head of eight companies of his Foot "in as good order as that black and dark night would admit.", probably assisted by a party of seamen from ships in the port. In fact the attackers seem already to have been repulsed with the loss of about 60 men. One Parliamentarian report claimed that no less than 30 of the casualties had been inflicted with one cannon discharge by the captain of the fort, and the "screeching and crying" of the wounded could be heard in the darkness.

With the situation at Maudlyn in hand, Birch led his men towards the nearby smaller fort of Little Penny-come-quick, whose defenders were suspiciously silent. As the Parliamentarians approached a voice from the fort demanded: "Stand, who are you for?"

"For the Parliament", replied Birch, a response which was met by heavy fire. Birch's men seem to have been somewhat nonplussed at this, but their commander urged them on with the observation that "it was safer to go on than retreat". The Parliamentarians stormed the fort, and in a fierce action killed or captured 66 Royalists. Among the prisoners was their commander, Colonel John Arundell, whose noticably short sword catching Birch's eye, the Parliamentarian commander confiscated it and wore it for the remainder of the war! Also rewarded for his part in the action was the captain of Maudlyn Fort, presented by Birch with "a piece of plate", which in fact cost the canny Parliamentarian colonel nothing, as it was part of the undeclared booty which had somehow found its way into Birch's hands when he had captured the Earl of Forth's coach and wife after the Second Battle of Newbury! [13]

Grenville had suffered a serious setback, and recriminations among the Royalist commanders were bitter, and, according to one Parliamentarian account, violent. In a letter Grenville blamed the failure on his reserves, complaining, "I have lately in the night attempted to force Plymouth works and took one of them nigh the Maudlyn work, and had my seconds performed their parts Plymouth (by all probability) had now certainly been ours" [14] The main blame seems to have been placed on Champernon's Regiment, which often appears to have been unreliable. The Parliamentarians claimed that a Council of War at Plympton, when Grenville's proposal for a renewed assault was met by accusations of rashness from Champernon, ended with the fiery Sir Richard pistolling Champernon and running his brother through!. In fact rumours of Champernon's death were at least greatly exaggerated, as he took part in the defence of Pendennis in 1646, and, despite being lamed for life by a leg wound, which may or may not have had any connection with "Skellum" Grenville, lived until 1684. [15]

Grenville was not finished yet, and called up as reinforcements Colonel Edward Seymour's Foot Regiment from Dartmouth. On the night of 17 February the Royalists, with a force including some of Thomas Hele's Horse and Champernon's Regiment, occupied the ruins of Mount Stamford Fort on the south side of the Cattewater. This was adjacent to the Parliamentarian-held Mount Batten, whose capture would enable the Royalists to fire across the Cattewater into Plymouth itself.

The Royalists set to work repairing Mount Stamford with a 12-foot thick rampart, once daylight came on the morning of 18 February attracting concentrated bombardment from Mount Batten and ships in the harbour. Robartes now sent a detachment of horse to make a demonstration on the north side of Plymouth, which successfully drew of most of Grenville's reserves. In the afternoon a force of 500 men including a number of seamen under the redoubtable Captain Richard Swanley, and a troop of horse, were ferried across the Cattewater to Mount Batten and launched a fierce assault on Mount Stamford. After a furious firefight the Royalists were driven out, losing a Lieutenant- Colonel, 11 other officers (some of whom were later shot as Parliamentarian deserters) and 112 men, for the admitted loss to the Parliamentarians of only one man killed. [16]

This reverse was the effective end of Grenville's attempt to take Plymouth. At the end of the month he was ordered by Prince Rupert to take the bulk of his men east to assist in operations against Taunton. Grenville, claiming the order was a ploy by Sir John Berkeley, Governor of Exeter, who wanted to take over his command, refused to obey until he received a reiterated order directly from the King, when he eventually sullenly marched off with his "New Cornish Tertia", leaving 2000 foot and 400 horse to continue the blockade of Plymouth.

Grenville would claim in his "Narrative" that Plymouth had been so reduced by a strict blockeering that the enemy horse were almost starved and lost and their foot grown almost to desperation, in such sort that if the said army had been suffered to remain but two months longer before that town very probably Plymouth had thereby been reduced into obedience." [17]

That this was at best wishful thinking on Grenville's part is fairly certain. Though there were some shortages, neither provisions nor morale in Plymouth had reached the low ebb which Sir Richard claimed.

In reality, Plymouth had withstood its last great test. Though the Royalist blockade would continue for almost a year, until finally raised by the approach of the New Model Army early in 1646, Parliament's hold on the town was never again seriously threatened.

[1] S.R. Gardiner, "History of the Great Civil War", London, 1893, vol.1, p.229

More Skellum: Sir Grenville's Attack at Plymouth 1645

THE FIGHT FOR MOUNT STAMFORD

NOTES

[2] For recent studies of Grenville and his forces see two articles by M. Stoyle, "The last refuge of a scoundrel:Sir Richard Grenville and Cornish particularism", Historical Research, 71 (1998), and "Sir Richard Grenville's Creatures: the New Cornish Tertia, 164446", Cornish Studies 4.

[3] Miller, op. cit., pp.67-8

[4] Grenville claimed in his own version of events (Narrative of Affairs in the West..." 1647) that he had only 300 men. But the higher figure given by Sir Edward Walker in his Historical Discourses..." London 1705, p.35 seems more likely to be correct.

[5] Clarendon, "History of the Great Rebellion" Oxford 1888, VIII, 133.

[6] Stoyle, "Grenville's Creatures", op. cit.

[7] The Arundells seem to have enlisted in the Royalist armies for the prime purpose of confusing later researchers. At least four "Johns" held field rank in the Western forces at various stages of the war. The one serving with Grenville was probably of Sithney, Cornwall, and later became Deputy Governor of Penclennis under Sir John ("Jack for the King") Arundell of Trerice. His regiment formed part of the garrison.

[8] quoted Stoyle, op. cit.

[9] Clarendon, op. cit. III, 425.

[10] Quoted Miller, p. 111

[11] E. 270 (14)

[12] Stoyle, "Grenville's Creatures", p.30.

[13] For the assault of 10/11 January, see A Perfect Diurnal, 15 January 1645, E.258(15), Exact Journal , 16 January 1645 E. 25(19); Military Memoirs of John Birch ed T.W. Webb) Camden Society, New Series vol VII, 1873, pp.14-15.

[14] British Library, Tanner MSS 286, f.203.

[15] P.R. Newman, Biographical Dictionary ... 1981, Item 273.

[16] See A True Relation of a Brave Defeat [of] "Skellum" Grenville 1645.

[17] ?

Back to English Civil War Times No. 55 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com