The 1643 successes of the Western Royalist forces of Sir Ralph Hopton, consolidated by the gains made that autumn by the Western Army of Prince Maurice, left the town and port of Plymouth as the only significant garrison in Parliamentarian hands west of Lyme. Its possession was important not only providing the Parliamentarian navy with a base of operations against the Royalist privateers and munitions traffic into the ports of the south-west, but as a potential "jumping-off" point for raids and more major incursions into Royalist-held Cornwall and Devon.

The 1643 successes of the Western Royalist forces of Sir Ralph Hopton, consolidated by the gains made that autumn by the Western Army of Prince Maurice, left the town and port of Plymouth as the only significant garrison in Parliamentarian hands west of Lyme. Its possession was important not only providing the Parliamentarian navy with a base of operations against the Royalist privateers and munitions traffic into the ports of the south-west, but as a potential "jumping-off" point for raids and more major incursions into Royalist-held Cornwall and Devon.

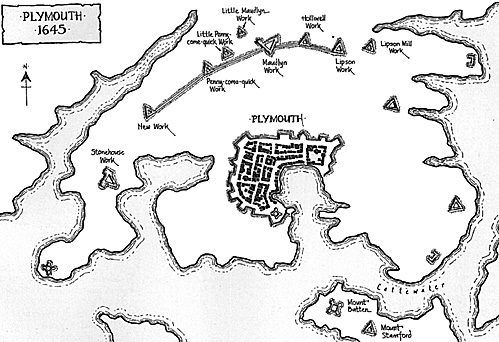

Well aware of Plymouth's significance, Royalist commanders had pursued a somewhat desultory blockade, and occasional closer siege operations, against the town since the early days of the war though without success. Parliament had been able to keep the garrison supplied by sea, and, despite some moments of crisis such as Maurice's attack of November 1643, Plymouth, protected by an increasingly formidable outer defence system of "sconces", forts and earth walls, and with a population overwhelmingly Parliamentarian in sympathy, withstood all the attentions of the King's forces.

The autumn of 1644, however, saw the defenders of the town faced by potentially their most serious threat so far. The ill-judged campaign in the West mounted by the Earl of Essex, with the relief of Plymouth among its stated objectives, had ended in disaster with the surrender of Essex's foot at Lostwithiel. On 5 September the combined forces of the Oxford Army, Prince Maurice and Sir Richard G renville's Cornish troops rendezvoused at Tavistock before moving against Plymouth. The defenders' situation seemed grim. Morale within the town was low, and there were for the moment only 800 men within the town to hold a defence line extending for four miles. There was every possibility that a full-blooded assault would carry Plymouth with considerably greater ease than Bristol in the previous year.

But the feared onslaught never occurred. After his summons was rejected, the King made an apparently half-hearted attempt on the northern side of the defences, and on 14 September, after further skirmishing, resumed his march east. The Royalist high command has been condemned for this decision, although Gardiner's claim that the failure to take Plymouth was a major cause of the eventual Royalist defeat is an exaggeration. [1]

In reality, severely under strength as a result of the Lostwithiel campaign, short of supplies and munitions, and at the end of a long and insecure line of communications, the Royalist forces were in no state to undertake a prolonged operation against Plymouth.

The task of blockading and, hopefully, eventually reducing Plymouth was given to Sir Richard Grenville. Grenville is one of the most villified of the Royalist commanders, many later writers taking their cue from the opinions of the Earl of Clarendon in his "History of the Great Rebellion", disregarding the consideration that Clarendon was motivated in his portrait by the prolonged and bitter personal feud which he had had with Sir Richard. Although some of the accusations levelled against Grenville, notably with regard to his ruthlessness towards prisoners and his tendency to use every opportunity to feather his own nest, are justified, he was also a highly capable soldier. [2]

Richard, brother to the famous Bevil, and a particularly debt-ridden professional soldier, had been serving with brutal effectiveness in Ireland on the outbreak of Civil War in England. He returned in 1643, and in December was appointed Lieutenant-General of Horse to Sir William Waller. But within three months he earned the opprobrium of all true Parliamentarians, and the nickname in their newsheets of "Skellum" Grenville, by deserting to the King, bringing with him most of his troop of horse and Parliamentarian plans for the spring campaign.

There is in fact some evidence that Grenville may have always been Royalist in sympathy, and initially adhered to Parliament primarily in hope of receiving the back pay due to him for his service in Ireland, but he did nothing to mollify his former employers by publishing a letter explaining his reasons for changing sides, and ending it cynically: "as I expect you would term me, your malignant servant, Richard Grenville." [3]

Grenville was now sent to Cornwall, in order to use his family influence to raise troops there. As well as recruiting a fairly small army and directing operations, without notable success, against Plymouth, Grenville also used his new-found powers to avenge himself on a number of his personal local enemies. His force of no more than 2500 men operated with some success alongside the other Royalist armies during the Lostwithiel campaign.

Taking over command at Plymouth in September 1644, Grenville initially had about 500 foot and 300 horse at his disposal. [4] With these he could do no more than establish his headquarters at Buckland Abbey and outposts at Plympton and Saltash in order to maintain a blockade of the town while he recruited his forces.

Unfortunately for the Royalists, this need to build up Grenville's forces probably cost them any real hope of taking Plymouth. Parliament appointed as its new Governor of the town their leading Cornish supporter, Lord Robartes. Robartes, whilst evidently a fairly unappealing character, had the kind of dogged determination which made him well suited for the task at hand. As Clarendon admitted, he was "one who must be overcome before he could believe he could be so." [5]

The evident threat to Plymouth, of which their fleet commander, the Earl of Warwick protested "If this town be lost all the West will be in danger", caused Parliament to order large quantities of supplies and considerable reinforcements to be sent. It is not clear how many of the latter actually materialised, but certainly arrived were about 800 men of Colonel John Birch's Regiment of Foot, a newly raised unit "gallantly set out by the Gentlemen of Kent", though Birch himself, formerly Lieutenant-Colonel of Sir Arthur Haseirigg's Foot, was a soldier of some experience. Also still in the town were various other units, including Samuel Harvey's Regiment of Horse, left there by Essex. Grenville later claimed the garrison to have been 5000 strong, though this is certainly a considerable exaggeration.

Grenville seems to have spent most of the autumn in recruiting his forces. He now commanded most of the Royalist troops in Devon and Cornwall, and was made High Sheriff of Devon, with authority over the local posse comitatus and militia units. Undertaking to raise a force of 1200 horse and 6000 foot, Grenville promised to reduce Plymouth before Christmas, and was granted the entire Cornish weekly assessment of £ 700 and it £ 1100 from Devon. He was also awarded the proceeds of a number of local Parliamentarians' estates in Royalist hands, including those of Lord Robartes.

Although critics, including Clarendon, who described him as "in truth the greatest plunderer of this war", accused Grenville of syphoning off considerable amounts of money for his own use, the fact remains that he had greater success than other Royalist commander at this stage of the war in raising and maintaining his troops. The core of Grenville's army consisted of what has been termed "The New Cornish Tertia" (to differentiate it from the "Old Cornish" of Hopton's former command). [6] This consisted of four Regiments of Foot: Sir Richard Grenville's, probably raised in the early summer of 1644, mostly in Cornwall, though with at least one Devon company; John and Richard Arundell's, mainly Cornish units, and Lewis Tremayne's. [7]

Tremayne recruited in both Cornwall and Devon, and there is a surviving note from him, probably written in September, which suggests that Grenville's men, certainly at this stage, were wearing civilian dress . This lists "the names of the parishes I have sent for to clothe their men, and the time of their appearance and how many of each parishe" [8] This suggests that Tremayne was hoping to recruit about 500 men in Devon, although he and most of his officers came from North East Cornwall.

Another important source of recruits for Grenville's army were the large numbers of Cornishmen (perhaps over 2000) who had deserted from Prince Maurice's army rather than march eastwards again after Lostwithiel. Many of these were highly seasoned veterans, and Clarendon goes so far as to suggest that Grenville actively encouraged them to desert in order to enlist them in his own units. [9]

Whatever the truth of this, they gave Grenville a hard core of capable men to form the basis of his new regiments. Parliamentarian accounts speak of great harshness being employed by Grenville's officers in mustering conscripts, which is quite likely, but it is equally the case that, once enlisted, the men of the "New Cornish Tertia" were much better cared for than their counterparts in any other contemporary Civil War unit except perhaps, at times, the New Model Army. Grenville wrote that he "neither would not could command men who were not paid", [10] and he made sure that his men were comfotably billeted and regularly paid. Even the Parliamentarians admitted that "he pays every soldier his pay every Saturday night, and each foot soldier duly receives 3s 6d" [11]

Although there is ample evidence of Grenville's harshness towards those who crossed him, he also seems to have made determined and largely sucessful attempts to limit the depredations carried out by his troops on the civilian population. He seems to have attempted to spare ordinary people from the main burden of supporting his troops whilst placing the onus on the gentry, thus winning a good deal of popular support which would lead later to grave suspicions of his eventual intentions.

The evidence justifies Stoyle's contention that of all the Royalist commanders in the latter stages of the war "it was Grenville who came closest to building an effective, well-balanced and potentially sustainable infantry force." [12] By December 1644 recruits were arriving in considerable numbers, and with basic training well under way, Grenville could begin to think of mounting more active operations than had hitherto been possible.

During the autumn Grenville had concentrated on attempting to win control of Plymouth by covert means. A Captain Joseph Grenville, sometimes said to have been an illegitimate son of Richard, though this is unlikely, was sent into the town poising as a deserter in attempt to subvert Colonel Searle, the Deputy Governor, into admitting the Royalists. The Colonel proved unreceptive, and Robartes hanged the young Grenville at the town gates. His action has been quoted as one of the reasons for the savage response of Sir Richard when the Parliamentarians surprised Saltash shortly afterwards. Retaking the town in a three-day fight, Grenville hanged a number of the garrison against the direct orders of the King.

Another scheme to infiltrate and set fire to Plymouth also failed, and by the start of 1645, it was clear not only that Grenville's boast of taking the town by Christmas had proved false, but that only a determined assault might do the business.

More Skellum: Sir Grenville's Attack at Plymouth 1645

Back to English Civil War Times No. 55 Table of Contents

Back to English Civil War Times List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com