Both contestants were now reasonably well aware of their opponents' situations. Johnson, knowing the French intention to move down the road from Niagara Falls to Fort Niagara, followed the siegecraft advice of Vauban and detached a force to contest their advance "at some distance from the fortess". He chose La Belle Famille, located equally about a mile from

Niagara and the main British camp. On the evening of July 23 Captain James De Lancey of the 46th Regiment of Foot was given 150 men from the light infantry companies of the 44th, 46th and 4/60th Regiments and ordered to take post at that spot. There, where the road emerged from the forest into the roughly 700 acres of clearing around Fort Niagara, he was to act as an advance warning post for the besiegers. De Lancey's men marched to theirpost, constructed a rough log breastwork a few yards to the left of the road and settled down for the night.

Both contestants were now reasonably well aware of their opponents' situations. Johnson, knowing the French intention to move down the road from Niagara Falls to Fort Niagara, followed the siegecraft advice of Vauban and detached a force to contest their advance "at some distance from the fortess". He chose La Belle Famille, located equally about a mile from

Niagara and the main British camp. On the evening of July 23 Captain James De Lancey of the 46th Regiment of Foot was given 150 men from the light infantry companies of the 44th, 46th and 4/60th Regiments and ordered to take post at that spot. There, where the road emerged from the forest into the roughly 700 acres of clearing around Fort Niagara, he was to act as an advance warning post for the besiegers. De Lancey's men marched to theirpost, constructed a rough log breastwork a few yards to the left of the road and settled down for the night.

From its landing place above Niagara Falls the French army had continued to advance - seven miles across the portage road to the Lower Landing below the escarpment and then a further six miles along the lower river to La Belle Famille. By the early morning of July 24 the French were less than a milefrom De Lancey's men and only about two miles from theirgoal of Fort Niagara. The size and composition of the French force had fluctuated since its departure from Venango. Many Indians had deserted while others had joined as the troops crossed Lake Erie. By the morning of July 23 Aubry and DeLignery probably had about 800 white troops and 500 Indians in the vicinity of La Belle Famille. The former were composed of colonial regulars of the Compagnies Franches de la Marine and substantial bodies of militia from Detroit and the Illinois Country.

While this formidable force poised for the attack, two developments occurred which would both alterthe French order of battle and delay their advance to the advantage of the British. Soon after sunrise on July 24 Captain De Lancey had his men hard at work improving their position. The log breastwork would offer cover, but its defense would be greatly enhanced by the addition of field artillery. De Lancey ordered a sergeant and ten men to cross the river to the battery opposite Fort Niagara and fetch a sixpounder. The party moved upriver to a gully which afforded a snug harbor on the west side of the Niagara. To do this the men had to move nearly a mile into the forest -- straight into the advancing French.

Somewhere near the gully and the boats this forlorn party was attacked and overwhelmed. Most were killed. Their heads and arms were cut off by the French Indians and mounted on poles. The firing had been heard, however, by De Lancey at La Belle Famille andby the officers in the main British camp. The besiegers were alerted that the French were near.

With their minor victory in hand, De Lignery and Aubry were prepared to sweep forward against the small body of redcoats at La Belle Famille. Just then, several Iroquois appeared from the direction of the British camp. They asked to speak with the French Indians. De Lignery and Aubry, always conscious of the importance of catering to the powerful Six Nations, permitted the conference and its attendant delay. The Iroquois asked the Indians of the upper lakes to stand neutral in the coming clash between the British and the French. To their horror, the French officers heard most agree! Almost a third of their force was suddenly gone! Only 800 white troops and as few as 30 western Indians remained to attack the British. Undaunted, De Lignery and Aubry formed their men and pressed on down the portage road.

By the time Captain James De Lancey heard the firing which signalled the demise of his boat detail at the gully it was slightly after 7:00 in the morning. The shots confirmed that the French were nearby. The Iroquois who had met with the French also reported that the French were close and coming on against the log breastwork at La Belle Famille. De Lancey had only his original 150 men to hold the position. Moments after hearing the shots he sent a sergeant running toward the British camp to warn Sir William Johnson and request assistance.

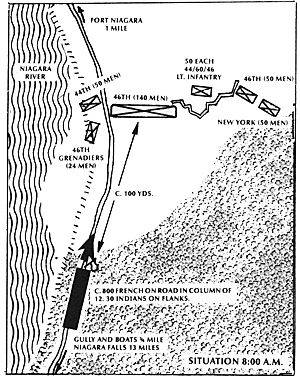

The balance of the available British force concentrated at La Belle Famille during the next 25 minutes. De Lancey's messenger passed the first reinforcements while on his way to Johnson. Three pickets of 50 men each had been dispatched to bolster De Lancey even before the firing began. They were drawn from the 44th, 46th and New York Regiments. Sir William responded to De Lancey's message by ordering up a further body from the 46th Regiment. Due to the demands of the siege this numbered only 164 men, including Captain James Marsh's greatly under-strength company of 24 grenadiers. Command of this third and final detachment for La Belle Famille was entrusted to Lieutenant Colonel Eyre Massey of the 46th.

By 8:00 Massey had arrived on the field, assumed command and deployed his 464 men in four two-rank detachments between the river and the edge of the forest. The redcoats stood across the road between the French and their goal.

By 8:00 Massey had arrived on the field, assumed command and deployed his 464 men in four two-rank detachments between the river and the edge of the forest. The redcoats stood across the road between the French and their goal.

The men of the 46th and the pickets were in the open, so Massey ordered the light infantry companies to leave the safety of the breastwork and follow their example. They obeyed, though with much grumbling and, as soon as Massey's attention was diverted to the French, peversely returned to the security of their log wall!

In addition to his regulars and provincials, Massey could also theoretically count upon the support of as many as 900 Iroquois ot the Six Nations. Their assistance, however, was problematic. Following several councils with French Indians inside Fort Niagara, the Iroquois had withdrawn from the British siege lines by July 14 and encamped at La Belle Famille. In their meetings with De Lignery's Indians on the morning of July 24 they had indicated their intention to refrain from the coming battle. In so doing the Iroquois influenced many of the French Indians to slip away from their Canadian and Illinois allies. It appeared that most of the Six Nations warriors would remain neutral until the outcome of the battle was certain.

The British, in fact, believed that only the Mohawks could be counted onto support them. The other nations might go either way. The action at La Belle Famille would, in fact, be primarly a clash of non-native troops. Only a few Indians participated on eitherside until the Iroquois enthusiasticallyjoined the pursuit after the French line had been broken.

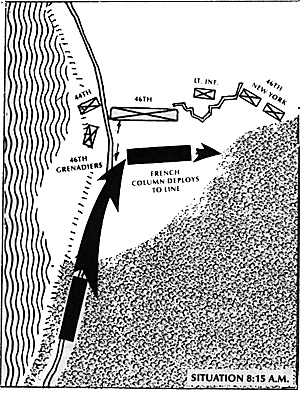

Massey had organized his defense with little time to spare. cetormed after the skirmish at the gully and the Indian council, the Army of the Ohio was moving rapidly down the road toward the clearing. Its 800 French troops were arrayed in a column of twelve which must have completely packed the width of the roadway. There was no advance guard, and, although the oak forest around them probably lacked heavy underbrush, there is no indication that flankers were employed. The few remaining Indians moved through the woods on either side. A pair of white colors were carried at the head of the French column. It was these banners which first caught Massey's eye as the French neared the edge of the clearing.

From accounts of the battle it seems that the French intended to attack in column and that the front ranks began to fire volleys from this formation as soon as they sighted the British. Once out of the confines of the woods the French began to deploy into line, largely to their right. A plan of the battle prepared in 1760 for Colonel Massey clearly shows this development.

The French continued to fire as they formed line to face what had proved to be a much larger British force than the expected 150 men. The maneuver was attempted under the intense fire of the battalion companies of the 46th Regiment in front and the particularly devastating musketry of Marsh's grenadiers and Bayly's picket of the 44th by then situated on the leftflank of the French. Colonel Massey later gave the credit for breaking the enemy line to the latter two companies.

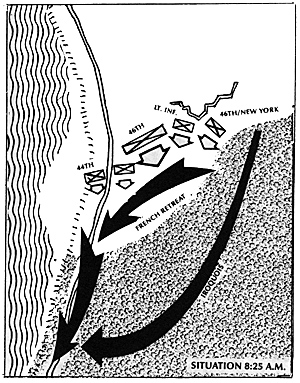

The chaos caused in the French ranks was compounded by the intensity of the British fire. The British received two volleys from those French who were able to fire. Once Massey ordered his men to stand and fire, however, they blazed away with terrible rapidity and discipline. The battalion men of the 46th apparently fired by platoons as a grand division, and their performance was so described by Massey. Accordingto the colonel, his men gave the French "seven rounds standing". He then ordered them to "advance by constant firing", and the redcoats thereby "gave them Sixteen Rounds, which made 'em give way". Many of the French troops never cleared the forest road and were thus unable to fire at all. As the first fugitives turned back into the road, the remainder of the column was compressed and, despite the best efforts of the officers to rally the men, they began to flee toward Niagara Falls.

That part of the French army which had entered the clearing and begun their deployment into line wavered to their right to escape the fire from the rightof the British line. This took them near the breastwork and De Lancey's light infantry which had yet to fire a shot. Their carbines soon came into action. By the time the light troops had discharged ten rounds, the French fire had slackened and the remnants began to withdraw into the woods. If the pickets of the 46th and New York Regiments at the extreme left of the British line fired at all it must have been at this point.

That part of the French army which had entered the clearing and begun their deployment into line wavered to their right to escape the fire from the rightof the British line. This took them near the breastwork and De Lancey's light infantry which had yet to fire a shot. Their carbines soon came into action. By the time the light troops had discharged ten rounds, the French fire had slackened and the remnants began to withdraw into the woods. If the pickets of the 46th and New York Regiments at the extreme left of the British line fired at all it must have been at this point.

The rout had begun. Massey and his 46th were moving foward, and he ordered De Lancey to do the same. The light infantry leaped over their breastwork and pursued the French toward the forest. Some resistance was encountered, so the French were not completely demoralized, but the resistance was quickly overcome. The British moved forward all alongtheir line. At this point occurred the most horrible development of all for the shattered French force. In the words of a British writer, the Iroquois, who had remained out of the action to this point, suddenly "fell on them like so many Butchers, with their Tomahawks and long Knives, hooping and shouting, as if Heaven and Earth were coming together, and kill'd Abundance of the Enemy."

The belated support of these native allies was a source of both disgust and bitterness for Colonel Massey and his fellow officers. Massey maintained that he had received no help from the Indians until the pursuit commenced. The Iroquois then did little but take prisoners and "Scalp'd poor Wretches, after they had fallen by our hands", he wrote. Disgust over their battlefield performance later turned to bitterness as most colonial and British newspapers awarded credit for the victory to Sir William Johnson and the Iroquois!

The British pursuit of the broken French force was slow and deliberate and swept up many of the French officers who had been wounded in the initial volleys. The Indians rushed ahead, driving the survivors up the portage road. Massey, fearful that he would march too far from the support of the main army, called off the chase four miles above La Belle Famille, probably in the vicinity of modern Five Mile Meadows. The Iroquois continued to harry the French at least as far as the Niagara Escarpment about two miles farther south. During their return to the battlefield the British troops gathered up other terrified and wounded French troops hiding in the forest or under the banks of the river.

Action at La Belle Famille

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com