The morning sun of July 24, 1759, beat down upon a solitary red-coated figure standing in a clearing. The officer paced a few yards, then glanced up a rutted cart track leading south across the flat terrain for about 100 yards. There it disappeared into dense hardwood forest. Another 100 yards to his left the clearing ended in more woods. To his right lay the mighty Niagara River, its green water running swiftly between fifty-foot banks.

The morning sun of July 24, 1759, beat down upon a solitary red-coated figure standing in a clearing. The officer paced a few yards, then glanced up a rutted cart track leading south across the flat terrain for about 100 yards. There it disappeared into dense hardwood forest. Another 100 yards to his left the clearing ended in more woods. To his right lay the mighty Niagara River, its green water running swiftly between fifty-foot banks.

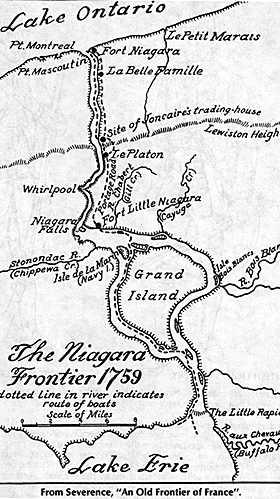

Fort From Severence, "An Old Frontier of France".

A mile to the north this strait joined Lake Ontario, and on the east point of the juncture stood Fort Niagara. The white flag of France floated above its walls, and nearby banks of powder smoke marked the guns of a British army which were relentlessly pounding the defenses into ruin. A light northwest wind carried the monotonous booming of artillery from the vicinity of the fort. Except for these few scars of war, however, the view was both pleasant and picturesque. A Seneca warrior had told British commander Sir William Johnson that the French knew this spot as La Belle Famille.

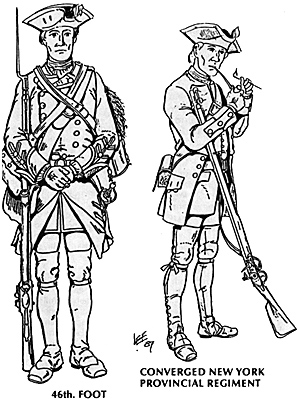

Lieutenant Colonel Eyre Massey was not alone in the wilderness clearing. A few feet behind him lay 140 men of the battalion companies of His Britannic Majesty's 46th Regiment of Foot. The two ranks of silent figures lay on their muskets. Those of the front rank had, at Massey's orders, fixed their bayonets. Two other knots of redcoats were visible to the Colonel's right. On the other side of the cart track lay 50 men of Captain Richard Bayly's detachment of the 44th Foot and a mere two dozen of Captain James Marsh's grenadiers of the 46th. Behind Massey's left shoulder was a crude log breastwork which sheltered 150 carbine-armed light infantrymen of the 44th, 46th, and 4/60th Regiments under Captain James DeLancey.

To Massey's extreme left, just visible before the forest closed in, was the termination of his thin line: 50 men each of the 46th and the New York Regiments. A few Mohawks could be seen filtering in and out of the woods at the margin of the clearing. Although Massey's men could see little but the grass before their eyes, their attention was directed southward where the road entered the woods.

Even though he stood erect, Massey himself could see very little. He paced a few more steps and then, in nervous frustration, clambered upon a halfrotted log. The Colonel stared at the dim opening in the trees but could still discern nothing of a French army hefeared might numberas many as 2,000 men. Their mission was to relieve Fort Niagara's 600 exhausted defenders. Massey was just as determined that his 464 soldiers would hold the road and protect the rear of the British siege lines which were slowly strangling the fortress of Niagara.

As Colonel Massey perched on his log a trio of Iroquois chiefs strolled through the prone ranks of the 46th. Casually, they glanced toward the forest and one remarked loudly that the French would soon appear with ten times the number of his small force. Massey winced at the comment as he heard a murmur of concern ripple through his battalion. Sensing his men's apprehension, the Colonel turned on his vantage point and, in a calm but firm voice, addressed those who could hear. "Lads, you know the French are coming. I can see their numbers," he lied, "and if you will obey me I'll engage them here and drub 'em." This reassured the men somewhat, and Massey once again turned his attention to the forest. At that moment he spied a flash of white among the trees.

Seconds later the road into the forest was no longer empty. A solid column off igu res fi I led the width of the path. A pair of white colors waved bravely at the head of this rapidly advancing body of men. A torrent of French soldiers, militia and coureurs de bois spilled from the woods. As they reached the sunlit clearing their shouts and cries became clearly audible to Massey and his waiting troops. Cheers of "Vive le Roi!" mixed with native warcries from the rolling mass of French and Indians as their officers urged them into the open.

The leading ranks had no more than cleared the edge of the forest before their muskets began to pop at what was visible of the silent British line. One of the first shots struck Colonel Massey, and the force of the blow threw him from his log. An ensign of the 46th rushed forward and propped up his stricken commander. Massey needed to see the French as they deployed into line to his left. Timingwas essential. Onward rushed the French, firing and cheering as they came. Their lead ranks were now only fifty yards away. In the midst of his pain Massey gave the command, and the battalion companies of the 46th Regiment rose to their feet. "Fire," he ordered, as the white-clad figures came within thirty yards of his line. A solid blast of musketry ripped into the French. Moments later Bayly's company and Marsh's grenadiers joined in from the right. The action had finally begun!

The leading ranks had no more than cleared the edge of the forest before their muskets began to pop at what was visible of the silent British line. One of the first shots struck Colonel Massey, and the force of the blow threw him from his log. An ensign of the 46th rushed forward and propped up his stricken commander. Massey needed to see the French as they deployed into line to his left. Timingwas essential. Onward rushed the French, firing and cheering as they came. Their lead ranks were now only fifty yards away. In the midst of his pain Massey gave the command, and the battalion companies of the 46th Regiment rose to their feet. "Fire," he ordered, as the white-clad figures came within thirty yards of his line. A solid blast of musketry ripped into the French. Moments later Bayly's company and Marsh's grenadiers joined in from the right. The action had finally begun!

The close range fight at the edge of the clearing would come to be known as the Battle of La Belle Fami l le. Its outcome would seal the fate of Fort Niagara and end eleventh-hour French aspirations to regain the military initiative in the Ohio Valley. Fort Niagara's strategic value faroutweighed that of mostof the posts scattered around the Great Lakes. It straddled and controlled the most practical route into the interior of the Great Lakes: the portage around Niagara Falls. Fort Niagara had blocked the British from the upper Great Lakes since 1726. Although the Colony of New York had obtained limited access to Lake Ontario with a post Oswego, French garrisons at Niagara and Frontenac (today Kinsgton, Ontario) barred any further commercial or military penetration of the interior. Fort Niagara guarded communications to Detroit, Michilimackinac and the other interior posts and held open the route between New France and Louisiana, France's other mainland North American colony. French efforts to extend their control to the Upper Ohio Valley, which sparked the French and Indian War in 1754, depended almost wholly upon troops and supplies sent across the Niagara portage from New France.

The conflict which had begun in the upper Ohio blossomed into full scale war in 1755. The well-known tale of General Edward Braddock's terrible defeat has drawn attention from the fact that a second goal of the 1755 campaign was Fort Niagara. William Shirley's army assembled as Oswego

but was unable to reach its weakly defended goal. Alarmed, the French replaced Niagara's wooden stockade with the most respectable defenses west ofTiconderoga. In 1756 the French temporarily removed the immediate threat to Niagara by destroying Oswego. The next two years would see a period of relative quiet on Lake Ontario. Fort Niagara remained the supply conduit for French forces operating in the Ohio Valley.

The conflict which had begun in the upper Ohio blossomed into full scale war in 1755. The well-known tale of General Edward Braddock's terrible defeat has drawn attention from the fact that a second goal of the 1755 campaign was Fort Niagara. William Shirley's army assembled as Oswego

but was unable to reach its weakly defended goal. Alarmed, the French replaced Niagara's wooden stockade with the most respectable defenses west ofTiconderoga. In 1756 the French temporarily removed the immediate threat to Niagara by destroying Oswego. The next two years would see a period of relative quiet on Lake Ontario. Fort Niagara remained the supply conduit for French forces operating in the Ohio Valley.

Situation

Although French successes continued into 1758, the situation in the West suddenly began to unravel late that summer. Fort Duquesne was captured by a British army. Even worse, a devasating surprise raid by Colonel John Bradstreet resulted in the destruction of Fort Frontenac and the elimination of the French naval vessels on Lake Ontario. The supply route to the West was disrupted, but fears of a similar raid on Niagara did not materialize.

Badly shaken, French authorities took measures to repair the damage. A strategy dispute flared between the Marquis de Montcalm, French military commander, who wished to concentrate troops and reources in the St. Lawrence region and Governor Francois Rigaud de Vaudreuil who hoped to counterattack in the Ohio and maintain the western campaign. An uneasy compromise was finally reached. New vessels were constructed on Lake Ontario and Fort Niagara was reinforced and placed under the command of Captain Pierre Pouchot. His troops could be used either to defend the post or to forward a campaign in the Ohio Valley. Most were eventually diverted for the latter purpose as the French prepared to retake Fort Duquesne. By the time his fortress was invested in July, 1759, Captain Pierre Pouchot could muster slightly more than 600 men to hold the walls.

British plans forthe 1759 campaign called for hammering New France from four directions. General James Wolfe would attack Quebec from the sea while General Jeffery Amherst's army moved down Lake Champlain against Ticonderoga, Crown Point and, ultimately, Montreal. Brigadier John Stanwix was to march north from Pittsburgh to Lake Erie and then on to Niagara. The fourth prong would be led by Brigadier John Prideaux. Advancing from Fort Stanwix, he was to reestablish a fort at Oswego, besiege and capture Niagara and then reverse direction and sweep down the St. Lawrence in support of Amherst's advance on Montreal. The captu re of Niagara would clip French communications with the West and protect the rear of Prideaux's force as it moved eastward.

Prideaux rapidly moved his army from Schenectady and Fort Stanwix to Oswego. Leaving the construction of the new post to Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Haldimand, Prideaux pushed westward along Lake Ontario with the 44th and 46th Regiments of Foot (1,330 men), the grenadier and light infantry companies of the 4/60th regiment (200 men), 650 picked men of the New York Regiment, 30 gunners of the Royal Artillery, and about 900 Iroquois under the leadership of Sir William Johnson. The army landed near Niagara on July 6 and quickly invested the post.

Much to their surprise, the British found the place far better fortified than expected and their own siege train embarrassingly weak. Wounds and incompetence among the engineers further delayed the progress of the siege. July 20 was the low point for the besiegers when they lost both Lieutenant Colonel John Johnston of the New York Regiment and Brigadier Prideaux himself. Much to the consternation of the regular officers, Sir William Johnson assumed command. Destpite their misgivings, however, Johnson prosecuted the siege with vigor. By July 23 a large battery was in place only 100 yards from the covered way and was wreaking havoc on the Lake Bastion of Fort Niagara.

Although the British had suffered their share of bad luck in the course of the siege, they had at least not found it necessary to contend with hostile forces outside the walls of Fort Niagara. Sir William Johnson had thoroughly attached the Iroquois to the British cause - even most of the Seneca, traditionally the nation friendliest to the French, had joined the expedition. Johnson's accession to command of the army had come about, in part, because the regular officers were grudgingly aware of the importance of Indian support to an army so deep in the wilderness.

Although the British had suffered their share of bad luck in the course of the siege, they had at least not found it necessary to contend with hostile forces outside the walls of Fort Niagara. Sir William Johnson had thoroughly attached the Iroquois to the British cause - even most of the Seneca, traditionally the nation friendliest to the French, had joined the expedition. Johnson's accession to command of the army had come about, in part, because the regular officers were grudgingly aware of the importance of Indian support to an army so deep in the wilderness.

This relatively stable state of affairs changed drastically about July 22 with news of the approach of a French relief force. Captain Pouchot had sent a call for help on July 7 as soon as he had confirmed that an enemy army lay beyond his walls. Pouchot's best potential source of assistance was the Army of the Ohio, then concentrating at Venango for a stroke against Pittsburgh. Many of these troops had been at Fort Niagara until June 1 when Pouchot, convinced that the British would not appear at Niagara for some time, deemed it prudent to divert them westward. These soldiers had joined the remnants of the army which had contested the capture of Fort Duquesne in 1758. They were reinforced by militia and colonial troops from the Illinois country.

Pouchot's message reached Venango on July 12. Niagara was besieged, learned Captain Francois Le Marchand de Lignery and his co-commander, Captain Charles Philippe Aubry of the Illinois contingent. Their plan to drive the British back beyond the mountains was temporarily foiled. Aubry and De Lignery had no choice but to aid Pouchot. To ignore his summons would be to abandon their supply line to New France. De Lingnery and Aubry rapidly moved troops, militia and Indians back to Lake Erie. Their force was impressive. By the time it arrived at the Niagara River it numbers around 1,400 soldiers and Indians.

As their fleet of small craft shot the rapids at modern Buffalo, it "appeared like a floating island, as the riverwas covered with their bateaux and canoes". The boats continued down the river to the Upper Landing situated about two miles above the fearsome cataracts. There the army disembarked at the charred ruins of Fort Little Niagara and began to march down the portage road. Aubry and De Lignery had already decided how to approach Fort Niagara. Although Captain Pouchot had suggested two options, they planned to attack head-on rather than slip down the west side of the river and cross over to the fortress.

In view of the results, this decision may seem rash. The leaders of the relief force were well aware of the dispositions of the besiegers, however. The British, they realized, were effectively split into five widely separated bodies. A sizeable camp and boat guard was at the landing place on Lake Ontario -- Le Petit Marais or the Little Marsh -- four miles east of the fort. Another detachment manned a battery on the west bank of the Niagara River.

Most of the Iroquois had withdrawn from the siege and encamped a mile above Fort Niagara at the place called La Belle Famille. The main camp was nearly a mile east of the fort, and much of the army was scattered in work parties, trench guards and gun crews throughout more than 800 yards of siege lines. De Lignery and Aubry undoubtedly believed that they could smash their way down the road and into Fort Niagara. The British later determined that the French officers who marched so confidently into La Belle Famille were certain that there was "no body to oppose them in that quarter".

The advance of this relief force, last hope of Fort Niagara, did not go unnoticed by the Iroquois. Sir William Johnson probably knew of their coming from his scouts as early as the evening of July 22. The next morning Indian messengers from the relief force passed through the British lines to deliver letters to Pouchot. These confirmed that help was at hand. The messengers simultaneously confirmed the British intelligence. On their way through the lines they parleyed with the Iroquois and Johnson himself. Among the Iroquois' assurances to DeLignery's Indian allies was that they would not "mingle in the quarrel" to come.

Action at La Belle Famille

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1989 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles covering military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com