To discover what had brought about this scene of confusion, we must look back to the winter and spring to understand this ninth day of July. Major General Edward Braddock had arrived in Virginia early in 1755 and thus secured the initiative. By April, the powerful army and siege train were almost ready to strike a telling blow, but that was not enough! Braddock's advance on Duquesne was only a part of London's plans for a sudden coup against the French. Washington's defeat at Fort Necessity the year before had helped convince London that British interests were seriously threatened in America. The ministry feared renewed conflict with France, but expected a small, faraway conflict in America would unlikely bring about a general war.

Hopefully French power in the colonies would be broken and British colonial expansion assured. To back these plans, the ministry prepared to add considerable might to their American forces. The 44th (Sir Peter Halkett) and 48th (Colonel Thomas Dunbar) regiments of foot, with a detachment of artillery, were dispatched in December 1754 from Cork, Ireland, to Alexandria, Virginia.

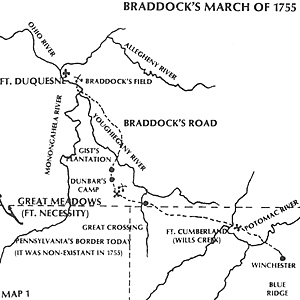

Soon after landing in Virginia Braddock met with the principle actors on the British side: senior naval commander, Admiral Augustus Keppel; Governor Dinwiddle of Virginia; Governor Sharpe of Maryland; Governor Morris of Pennsylvania; Governor De Lancey of New York; Governor Shirley of Massachusetts, and William Johnson, a key Indian trader in the Mohawk Valley. Operating with detailed instructions from home, and keeping in mind London's desire for a quick decisive victory, the commander-in-chief listened to his councilors' suggestions, and a plan was arranged. See Map 1.

In addition to the General's advance on Fort Duquesne to oust the French from what is now western Pennsylvania, Governor William Shirley and Sir William Pepperell were to reinforce the most northerly British post of Oswego on Lake Ontario from their two newly-raised regiments of provincials and then march westward against Fort Niagara. Meanwhile, a local regular detachment from Nova Scotia and 2,000 New England volunteers were to seize fort Beausejour at Chignecto in Acadia. Finally, to ensure a complete victory, Indian Superintendent William Johnson was to lead a 4,400 man force of provincials against Fort St. Frederic at Crown Point in the Champlain Valley corridor. [3]

ED. NOTE: See the map in the article entitled, "The French and Wars 1744-1766".

Having prepared the overall campaign to ruin French interests in America, Braddock, a forty-year veteran who had risen through the ranks of the Coldstream Guards, turned to his own immediate needs. He had to march through several hundred miles of relatively empty territory and snatch Fort Duquesne from the French. In this new assignment, however, administrative experience learned when acting as military governor of Gibraltar appeared more useful than his years in the Guard. His American responsibilities were to be more than simply marching out and seizing a fort. First he had to sort out the tangled problems of preparing the colonies for war. This meant recruiting Americans to strengthen the regulars, recruiting Indians as scouts and warriors, organizing the provincial contingent, and creating a supply and transport system. Poor organization and planning had often been the nemesis of colonial campaigns against the French and Indians in previous wars.

In addition to long distances, harsh terrain, and miserable roads, colonial planners always faced irascible jealousies and rivalries in neighboring colonies when laying out campaigns. Braddock faced the same hurdles - most important was transportation for supplying 2,500 men for three months and things weren't going well.

By April Braddock's agents had acquired only 25 of the 150 wagons required. Fortunately, Pennsylvania Postmaster Benjamin Franklin had been sent to the Army to see what the Post Office could do to facilitate army communications. In the course of conversation Braddock mentioned the sorry state of his transport. On hearing the general's tales of woe, Franklin remarked how unfortunate it was that the general was not in his state because wagons were plentiful there. Seizing upon this opportunity, Braddock eventually struck a deal with the postmaster and Franklin set out to acquire 150 wagons and some pack horses for the army. Starting 26 April 1755 he advertised the requirements of the crown in his newspaper and within a fortnight 150 wagons and 259 carrying horses were on the way to the British camp at Fort Cumberland. The transportation problem had been solved.

[4]

Having demonstrated his administrative sagacity by placing canny Ben Franklin in the role of wagon contractor, we should not be surprised that Braddock sought out William Johnson, a renowned Mohawk Valley Indian trader, to be superintendent of the Iroquois Confederacy. Having no personal experience with Indian affairs, Braddock enrolled the most qualified man to handle the job for him. But Johnson's influence did not extend to Virginia, and could be of little help in securing native allies for the Duquesne expedition.

Instead, the perennial problem of intercolonial jealousies nullified Braddock's efforts to persuade the Catawha and Cherokee Nations to help. Governor Dinwiddle of Virginia, long an activist against the French, had bypassed Governor Glen of South Carolina and contacted the tribes himself. Glen felt Dinwiddle was overstepping his authority. To thwart his rival's plans, Glen called a conference of the two tribal leaders to be held in June, just when Braddock needed them most. Apparently looking for an excuse to avoid confrontation with the French, the Indians flocked to Glen's meeting.

In consequence, Braddock's subordinates only managed to scrape together eight native guides. As had so often been the case in the past 66 years, the

pettiness of colonial interests waylaid another joint effort against New France.

[5]

Having few Indians to act as scouts, Braddock did his best to protect his men without them. Over 300 men would be detailed to march on the column's flanks and a strong advance guard of a further 300 men were to prevent surprise. The individual was considered as well. At Fort Cumberland he responded to the problem of the men being overloaded with equipment by having them leave much of it behind. The official orders read, "The soldiers are to leave their Shoulder Belts, Waist Belts and hangers behind and only take with them to the Field one spare shirt, one spare pair of Stockings, one spare pair of Shoes and one pair of Brown Caters.' Lightweight waistcoats and breeches replaced the heavier regulation uniforms, and leather bladders were inserted in all hats to protect the wearer from sunstroke. Officers and sergeants discarded their espontoons and halberds replacing them with fusees." [6]

While George II's ministers had been planning their master stroke, the Ministry of Louis XV had not been idle. Word had reached Paris of plans to send one thousand British regulars to America, so France upped the ante by shipping 3,000 of their own professional fighters to New France. To counter, Vice Admiral Edward Boscawen left Plymouth with thirteen sail and orders to intercept and detain the French convoy.

In a fog off the American shore, Boscawen captured the L'Alcide and Le Lys, two 64-gun warships sailing "en flute" along with the eight companies of soldiers they carried. From that day an undeclared, far-away war had begun. The actions of Boscawen caused France to withdraw her minister from London and the two nations ceased efforts to avert war (if anything, quick success was even more urgent).

More French and Indian Wars: 1744-1766

Introduction

Planning the North American Campaign of 1755

French, Indians, and British Forces

Wargame Scenario and Battle

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VIII No. 1

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com