These two preliminary encounters were both victories for the FrancoPiedmontese armies. At Montebello Forey's French division with the aid of a Piedmontese cavalry brigade and some Chasseurs d'Afrique took on and defeated an Austrian corps by overrunning its brigades in detail. in my reduced scale that would come to at most 13 French infantry bases, 1 base of Chasseurs d'Afrique, 2 of Piedmontese heavy lancers. The Austrians would have 25 infantry, 1 cavalry base. The French artillery was outnumbered a reduced value base to 3 f A ones, or 72 guns to 12.

These two preliminary encounters were both victories for the FrancoPiedmontese armies. At Montebello Forey's French division with the aid of a Piedmontese cavalry brigade and some Chasseurs d'Afrique took on and defeated an Austrian corps by overrunning its brigades in detail. in my reduced scale that would come to at most 13 French infantry bases, 1 base of Chasseurs d'Afrique, 2 of Piedmontese heavy lancers. The Austrians would have 25 infantry, 1 cavalry base. The French artillery was outnumbered a reduced value base to 3 f A ones, or 72 guns to 12.

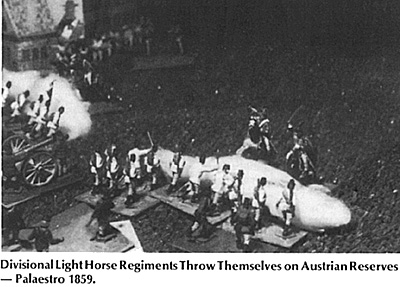

In the battle at Palaestro the Piedmontese Army of 5 large divisions was attacked while crossing a river by an Austrian corps, effectively the same as that engaged at Montebello. The first day's fighting was inconclusive, but a French division arrived the next day, and a Zouave regiment carried away one of the Austrian brigades with a bayonet charge. For those using other systems, the Austrian corps usually consisted of 2 divisions, one of 2 brigades, the other of 3, each brigade having a regiment of 3 infantry battalions nominally 1,000 men, but actually a shade under 800, a jager or borderer battalion of around 1,000 men, and a light or horse battery of 8 smooth bore guns. Another 3 to 4 batteries, sometimes of medium guns, and a cavalry force of either a regiment or 4 squadrons numbering 550-850 sabers (or lances) completed the combattants of the corps.

French corps varied but were essentially as for 1870, but with fewer 3 division corps and no Mitrailleuses. Italian units were about 400 men to the cavalry regiments, 4 battalions of 500-600 men to the regiment, 2 regiments to the brigade, 2 brigades a Bersaglieri battalion and a light cavalry regiment plus 3 batteries of 6 smoothbore guns to the division.

French corps varied but were essentially as for 1870, but with fewer 3 division corps and no Mitrailleuses. Italian units were about 400 men to the cavalry regiments, 4 battalions of 500-600 men to the regiment, 2 regiments to the brigade, 2 brigades a Bersaglieri battalion and a light cavalry regiment plus 3 batteries of 6 smoothbore guns to the division.

To liven things up I run both Montebello and Palaestro together. The Austrian force is ordered to push forward on two roads - either on different tables or some distance apart on a large table. Each corps commander is ordered to push on to the named town, seize it, and attempt to drive the enemy back. Sometimes orders involve driving the Piedmontese to the south (away from the expected rendezvous with the French). However, if the main French Army is encountered, fight a delaying action and send word of its location. The Sardinian commander is to seize Palaestro and push on to link upwith the French, sending forces north to make contact with the French. The French commander is ordered to seize Montebello and await contact from the Piedmontese. Usually the Piedmontese commander only has 2-3 divisions and his divisional cavalry on the assumption that the two brigades of the Cavalry Division are operating to the north with a view to making contact with the French.

If neither group of players knows the scenario (as indeed neither the Austrians nor the Allies did in 1859) interesting results develop. The Piedmontese are outgunned and facing superior numbers, and the Austrians have orders to attack. The French, on the other hand, are badly outnumbered except in cavalry, but the Austrians don't know that, and are not required by their orders to attack. Hidden movement for troops behind front line formed units and cavalry forces at the start of the game could keep the Austrians in the dark for the entire game since they have insufficient cavalry to challenge the French.

Once the scenario is known it becomes necessary to mix things up. In place of Forey's lone division could be the vanguard of a French corpsperhaps that of the guard! The Piedmontese could be reduced to a lone division supported by the cavalry division. Two Austrian corps could arrive at one of the towns perhaps with conflicting orders.

To customize circumstances to the Italian campaign of 18591 usually make certain adjustments. Italian and French line infantry shoot badly at long ranges because they lack leaf sights. Austrian line infantry and borderers shoot badly against attacking infantry because they have leaf sights but aren't very good at dealing with changing ranges. French troops are encouraged (sometimes by adding a point to morale rolls when ordered to charge) to close range as a point of tactical doctrine. Austrians and Italians are not.

At the command level I usually don't assign particular values to commanders in the manner of WRG or Paul Koch, to mention but a few. On the other hand, I am not above tailoring victory conditions to encourage some commanders to try to hang onto their troops and others to win glory. For 1859 it appears to me that most Austrians corps commanders as well as Piedmontese commanders up to and including the King were more or less concerned with staying out of trouble others, like Benedec, would try to figure out the sensible thing and do it. French commanders were encouraged to close with the enemy - partly because they had inferior rifles, partly because Gloire was a big thing in the Empire.

Among the Allies, Victor Emmanuel was in unquestioned control of his army, but was inclined to listen to his senior partner, and Napoleon III was free to make pretty much any mistake he wanted to. Among the Austrians, however, Franz Joseph did not arrive in time for any battles before Solferino, and there seemsto have been some question as to whether anyone else was in overall control, although the various Austrian armies did have commanders. Army and corps commanders ran from fair to poor, with Benedec being good, and Clam Gallas at best a Poltroon.

More Scenarios for 1859

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. VII #5

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com