Musketeer and grenadier NCO's, 1806. (Kling)

Generally speaking, one can divide writings on the subject into

two broad groups-firstly those that see the period from Frederick's

death to 1806 as one of conservatism and reaction, with 1807

marking the beginning of the period of proper reforms; and secondly

those that see the entire period as one of continual reform. Most

Anglo-American historians tend towards the first view, perhaps

because they are unfamiliar with the German sources and lack depth

of knowledge on the subject and thus do not consider the "gray"

areas, but instead see things in terms of "black" and white". Ironically,

East German historians share this position, examining the social

forces at work in terms of "feudal reaction" and "bourgeois

revolution". However, the noted historian and journalist Sebastian

Haffner puts over the second outlook rather well in his recent work

Preussen ohne Legende (Hamburg 1980), pp. 168ff:

"We must get away from this legend. It is not only an

oversimplification, it is a falsification of actual history. The whole period is

in reality one unit. The same people and forces were at work the whole

time. The two most important reforming ministers, Stein and Hardenberg,

were Prussian ministers prior to 1806, the most significant military

reformer Scharnhorst was already deputy chief-of-staff ...

"The Prussia of the 18th Century was not only the newest but also

the most up-to-date state in Europe, strong not by tradition, but by being

modern. . . " The above should be borne in mind when considering the

catastrophe of 1806. I now wish to consider a number of points

raised in Major Lawson's contributions.

"FREDRICIAN"

My reasons for objecting to the use of this term to describe the

army of 1806 were outlined in THE COURIER 111/5, pp.18ff. If we are

to accept the point that the army of 1806 was "Frederician", then why

stop there? We could also apply the term to the army of 1813. After

all, the canton system modified in 1792 (2) was still in use until

1813/1814, there were still foreigners in the army (3), most of the drill contained in the 1812 Regulations had been in use in 1806 (4), soldiers were still flogged (5), the officer corps was of more or less the same composition (6), guns were still scattered amongst the infantry (7), and so on. As there were but few significant changes between the army of 1806 and that of 1813, then both are almost equally "Frederician" or "non-Frederician" , depending on your pointof

view. It is interesting that the noted military historian Siegfried Fiedler

describes the army of 1806 as "post-Frederician" (8). That would seem to be the best term to use.

Foreigners:

Anglo-American historians tend not to appreciate fully what the

word "foreigner" means in the context of the Brandenburg-Prussian

army at the time in question. The word "foreigner" here does not mean

non-German, it means non-Prussian. Prussians were largely of either

German or Polish extract, a small number were descendants of

Huguenot refugees.

The Polish-speaking inhabitants of the newly acquired Catholic

province of South Prussia were thus natives; the German-speaking

inhabitants of Lutheran Brandenburg were also natives, but the

German-speaking inhabitants of Lutheran Brunswick were

foreigners. Dedicated servants of the Prussian state and leading

German nationalists like Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Stein and Bluecher

were foreigners. What nationalistic 'espirit de corps' did the native

Prussian Polish recruits of the West Prussian militia have in 1813 when they deserted in droves? (9)

Did foreigners like Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Stein and Bluecher

"not share whatever nationalistic 'espirit cle corps' that one might

expect of the natives"? After the break-up of the army on the retreat

from Jena-Auerstadt more so-called "foreigners" managed to furtively

get back to the regrouping areas in East Prussia and Silesia than

"natives" . (10)

That doesn't seem to indicate a lack of nationalistic

'espirit de corps'. To continue on this point, Yorck wrote in 1820:

"The foreigners were not as bad as the learned gentlemen believe, and

I fear very much that the Rhineland or Posen militia would ever be

better. " (11)

That is a point to consider, especially when compared to the

"patriotism" and "nationalistic espirit de corps" of Napoleon's 'grande

Armee'. That consisted of French, Dutch, German, Italian and Swiss

recruits. The Prussian army with its Germans and Poles was more of

a national army than that of Napoleon. Finally on this point, Luetzow's

Free Corps of 1813 consisted mainly of "foreigners", yet it is often

regarded as the living symbol of German nationalism. Certainly there

were problems caused by the recruitment system of the Prussian

army and changes were made during the course of the Napoleonic

Wars, but to dismiss the "foreigners" as a "bad lot" is very one-sided.

"Die Kluft zwischen Mann und Offizier": Did "little or no empathy

exist between them"? It is hard to make such a sweeping statement

without having read a large number of memoirs and without having

done a good deal of research. All I have come across in the way of

memoirs of participants in the 1806 campaign are those of Friedrich

Wilhelm Beeger (12) and Wilhelm von Doering

(13). The former was a

private in 1806 and was promoted to lieutenant by 1813, so 'die Kluft' was not insurmountable in his case.

The latter joined the army as a 'Junker'and was taken prisoner at

Jena. Page 59 of his memoirs seem to indicate that a little more than

empathy existed between him and certain other soldiers. Perhaps the

above are isolated instances contrary to the general rule, but as I

have no other material to consider at present, it is difficult to see the

matter differently.

DISCIPLINE AND PUNISHMENT

Discipline in the Prussian Army could be harsh and punishment

severe, but that was little different from the armed forces of other

nations at the time. Was pressganging for the Navy in Britain more

civilized than press-ganging for Frederick's army? Clausewitz, when

a prisoner-of-war in France, made the following entry in his journal on

25th August 1807:

"it is true that in France all administrative processes are

characterized by extreme military tendancies; but there is no trace of

these in the character of the nation. Two or three gendarmes leading

thirty or forty conscripts, tied two by two, on a single rope to the

prefectures, proves both points at the same time. The first, because

this economical method saves gendarmes; the second, because the

shameful procedure suggests extreme compulsion. " (14)

I have yet to come across any account describing such extreme

measures being used in Prussia to get conscripts to report for duty.

Yet many writers and historians tell us of the extreme compulsion in

the Prussian army and the nationalistic 'espirit de corps' in the French

army.

The facts seem to be that throughout the period in question, the

Prussian Army was becoming increasingly liberal and punishment

was not so harsh as during the Seven Years War. In fact, a number

of Prussian regiments had a reputation for humane treatment of their

rankers. As General von Warnery (1720-1786) said: few troops [are]

beaten less than in certain regiments . . . (15)

I think it would be best to conclude that discipline and punishment

were probably no more severe in the Prussian Army than in others at

that time, and could have been less so.

MOTIVATION

Was it just harsh discipline that motivated the Prussian soldier? It

can be argued that there were a number of other reasons for

motivating the recruit, be he "foreigner" or "native". One of the

advantages of the Canton System was that recruits from the same

areas and villages were placed together in the same unit. Any

misdemeanor could become general knowledge in that village, likewise

acts of bravery. Personal and local pride was therefore motivation in

some cases. And as for the foreigners, a number of them were

soldiers by profession. If they performed poorly in Prussian service,

they were less likely to obtain employment elsewhere, so their

professional pride may have provided them with a degree of

motivation. Not to be forgotten is that old soldiers with a good record

were often rewarded with jobs in the civil service, post office, etc.

There was a good deal more motivating the Prussian soldier than the

threat of a beating.

THE OFFICER CORPS

Anglo-American historians often make the error of saying that

there were very few bourgeois in the officer corps and that it was an

exclusive aristocratic club. It is true that the officer corps and

especially particular branches of it were dominated by the nobility, but

access to it was not as restricted as some would have us believe.

What is often forgotten is that men of humbler origin were ennobled

for meritorious service or as part of their promotion to higher rank.

To go through a list of officers and comparing the number of those

with a 'von' in their name with those who do not can be misleading.

Take Scharnhorst as one example. He rose to the rank of Lieutenant-

Colonel in Hanoverian service. He joined the Prussian army with that

rank in 1801. In 1802 he received his patent of nobility and became

Lieutenant-Colonel von Scharnhorst instead of mere Lieutenant-

Colonel Scharnhorst. (16)

This is not to deny that the officer corps

was the preserve of the aristocracy, rather, it is an attempt to show

that access to it by men of humbler origin was not as restricted as

some say and that men of humbler origin were at times assimilated into

the nobility and that some of the statistics quoted often hide this fact.

Another point which should not be forgotten here is that the word

"aristocrat" does not have quite the same connotation when applied

to the Prussians as when applied to the French or English. The

Prussian nobility was as a whole a good deal poorer than their

western European counterparts and thus the gap between the

Prussian aristocracy and pesantry was not as great as in some other

countries and therefore probable that mutual understanding was greater.

AGE OF THE OFFICER CORPS

The age of the senior commanders in the Prussian army in 1806 is

often presented as a major problem * However, for the sake of

balance, it should be pointed out that the youngest senior commander

on both sides was a Prussian, Prince Louis Ferdinand. The third

oldest Prussian senior commander, L'Estocq, played such a

successful role at Eylau that his age is overlooked. The fourth oldest,

Tauentzien, commanded a corps in the Wars of Liberation, by which

time he had become older than the Duke of Brunswick was in 1806;

Bluecher had certainly not become any younger either and Grawert

went on to command the Auxiliary Corps in Russia in 1812.

The senior commanders of the German forces in the war of

1870/71 were of a similar age to those in 1806, but as the former

won, no one seems to complain about their age. We also have to bear

in mind that the youthful French marshalate was unique in Europe-no

other country had undergone such a revolution and removed the

upper echelons of power.

Finally, it shouldn't be forgotten that the junior officers of the

French army were no striplings. The average captain was older than

Napoleon, Mortier, Bessiers, Ney, Soult, Lannes, Davout and Murat.

The average lieutenant was the same age as Napoleon (17). These men had learned their trade in the days of the 'ancien regime' as had

the Prussian officer corps.

LOGISTICAL SUPPORT

As Mr. Lawson points out, in 1806 the Prussian supply train was

cumbersome yet unable to properly support the army. Attempts to

modernize and streamline it were made prior to 1813, yet time and

again, Prussian soldiers went hungry and unshod. In August 1813,

much of Bluecher's Silesian militia deserted and went home simply to

get something to eat (18). Yet such a poorly supplied and fed army

won several battles.

Furthermore, Bluecher's "Army of the Lower Rhine" similarly went

hungry but still managed to march through broken, muddy

countryside, fight a grueling battle and conduct a pursuit. Lack of an

adequate supply system in 1806 may well have contributed to defeat,

but the fact of the matter is that hungry, half-naked soldiers can still

win battles, as they did in 1813.

ARTILLERY

The artillery was, as a whole, mishandled in 1806. Certain reforms

were undertaken prior to 1813, including the abolition of battalion guns

and the formation of artillery reserves. However, that does not mean

that artillery used in 1813 was dramatically better. Battalion guns as

such may have been abolished, but each brigade now had a foot

battery which was used in a similar fashion (19).

Indeed, in the

"Instruction of 10th August 1813", Frederick William complained that

the guns were dispersed too much and used too early. (20)

Complaints similar to these were made about the artillery in 1806.

FREDERICK & LIGHT INFANTRY

As far as my limited knowledge goes, Frederick the Great's

writings did not influence French light infantry tactics. I have never

come across a statement to that effect and certainly have never

made one.

REFORMS PRIOR TO 1806

At this time there were no 'Schuetzen' battalions in the Prussian

Army, the first was formed in 1808. Prior to this, the 'Schuetzen' were

the rifle-armed sections of the line and light battalions. There were in

fact three battalions of 'Jaeger' which together formed the Field

Jaeger Regiment.

THE "WORST MUSKET IN EUROPE"

If the Prussian musket was

"abysmally poor", then why? Clausewitz's oft quoted but seldom

understood critique comes in his essay "Preussen in seiner grossen

Katastophe" written in 1823/1824 (21). From this essay it is not

entirely clear why Clausewitz held this view but the context in which

this comment was made would seem to indicate that the reason was

because the barrels were polished so often that they tended to

become so thin that they were prone to explode when fired.

Others than Clausewitz complain about the shape of the stock of

the 1780 model and this was modified before 1806. The shape of the

stock hindered aimed firing and thus the weapon was not suitable for

skirmishing line infantry. (The light infantry, however, had other, better

designed weapons.) But for the purpose for which it was designed,

namely for firing rapid volleys, the 1780 Model was an ideal weapon.

Furthermore, a French officer once commented:

"The Prussian soldier could not be better armed, the muskets and

locks are made with infinite care. The alterations made to it are

recognized as very advantageous. The soldier easily fires six times

per minute (we can only fire three times with our arms)." (22)

20,000-30,000 of these muskets were sold to Poland in 1789 and

1790; 30,000 to Spain in 1795; 57,000 to Swiss agents in 1798 and in

1804 100,000 were exported to America (23). Clearly, a number of people thought it was a fine weapon. It would therefore seem that the

fault with the Prussian musket was not the 1780 Model itself, but that

due to financial constraints, worn weapons were not replaced.

REGULATIONS FOR SKIRMISHERS

I don't agree that because a "...mere 4 paragraphs (of the 1788

light infantry regulations) are devoted to what might be called

'skirmish tactics' . . ." that ". . this meant that most Prussian officers

found 'the old method of forming a firing line three ranks deep and

advancing on the enemy' perfectly adequate." The amount of space

devoted to a subject in a set of regulations does not indicate the

frequency of its use.

If one compares this section of the 1788 regulations with the

same section in the 1812 regulations, then it is apparent that the latter

were also a "mere 4 paragraphs" and it should follow that the

Prussian officers in the Wars of Liberation were also reluctant to use

skirmishers. Yet historians and critics such as Paret (24) insist that

the Prussians used a large number of skirmishers at this time. The

whole point of skirmish tactics is that they are left to individual

initiative and not regulated.

THE BATTLE OF JENA

Very few recent accounts of this battle actually derive from

French or German language sources. Surely that is where the most

significant primary and secondary accounts would be found.

Perhaps it would help here to translate extracts on events in the

battle into English, to see if a different interpretation might be obtained.

We are often told the story of 20,000 Prussians standing

motionless before Vierzehnheiligen for two hours and being mowed

down by French 'tirailleurs', or that Hohenlohe's men were standing

aimlessly in front of Vierzehnheiligen unable either to deal with the

French skirmishers or to take the village because they were not

trained in street fighting. However, reference to the accounts of

eyewitnesses and secondary sources give quite a different

perspective.

Let us first establish how many men Hohenlohe had at

Vierzehnheiligen. The last returns made before the Battle of Jena

were on 6th October 1806 (25). These show Hohenlohe's entire force at a strength of about 42,584 men. Taking into account losses

suffered in the following week, it is estimated that he went into action

at Jena with about 36,800 men.

Taking into account the detachments and forces spread all over

the battle area, the defeated formations under Tauentzien and Dyherrn

reforming to the rear, is it reasonable to suggest that over half of the

troops remaining to Hohenlohe were deployed around a single village?

What the Prince in fact had deployed around Vierzehnheiligen was

eight battalions of infantry whose combined strength a week

previously was 5,751 men.

About 3,500 cavalry were deployed to their flank and rear and

three artillery formations were deployed in their support. The

combined total of these forces could not have been much more than

9,500 men, and as the cavalry were not engaged in the firefight, the

actual figure was nearer 6,000 men, not 20,000. The rest of the story,

when taken from sources who use this figure, is also much

exaggerated, as we shall see.

Now, to the official report of Major von der Marwitz, adjutant to

Prince Hohenlohe, for the inquiry into the defeat in 1806 (26).

"Our infantry attack, before which the enemy skirmishers fell back,

now came up to the village Vierzehn Heiligen where a line was

formed again and the left flank was taken slightly around the village . .

. The village was occupied by the enemy in strength, and behind it,

out of our line of sight, he had squeezed together strong columns or

was bringing them up. It seemed as if we wanted to take the village

by fire. We were standing only a few hundred paces from his

batteries and the hail of cannister wrought an incredible devastation

in our battalions which we could not replace with anything. Our

artillery almost flattened the village and the oldest soldiers, Prince

Hohenlohe himself, affirmed to having had no concept of such fire.

Along the entire line, one battalion volley followed another, without

effect in many places. The area at the entrance to the village was,

however, the scene of a fearful murder and loss of blood. . .

"One battery which had moved up close to the village bombarded

it as forcefully as possible for half an hour, but as the enemy

continued to stand behind the closely packed houses and sheds, it

could not be taken this way. The gunners requested permission to

fire incendiary shells into it. This was granted and the first set it

alight. Now the enemy began to withdraw and if only we had continued

this bombardment of incendiaries for a quarter of an hour then

nobody could have stayed in it or got through it and we would have at

least secured our retreat ... But after firing hardly more than a couple

of shells, it was stopped ...

"The enemy's fire ceased for a moment; perhaps this was the

moment when according to French reports the remainder of Ney's

Corps and the Reserve Cavalry arrived and when the enemy decided

to send in his infantry-held back for so long-as all the skirmishers

fell back on their corps and it was, as already mentioned, quiet for a

minute. We could see no other enemy than right in front of us in

Vierzehn Heiligen and behind this village. So the Prince decided, as

he thought this final effort necessary, to send a few battalions into it

and take it with the bayonet, but just then General Grawert rode up to

him and-~ongratulated him on winning the battle. The Prince did not

want to accept this congratulation and told General Grawert of his

decision to have the village attacked. But the latter requested that he

should delay it. He pointed to our half-ruined battalions which had

stood for two hours in uninterrupted fire, to the single line with no

reserve . . . and concluded with the remark: 'We can and must hold

this position until General Ruechel approaches with his corps and

then we can make the victory complete, taking the village, but if one or

a couple of attacks were beaten off, then we would have a hole in the

line which could not be filled and which the enemy would certainly

exploit and rob us of victory!'

"The Prince agreed with this judgment and we stayed there ...

"The enemy now had Augereau's Corps move through the

Isserstedt Forest and through isserstedt from where our few light

troops were soon driven off, and in doing so, found himself on

our right flank and in the rear of the Saxons in the 'Schnecke' . . .

Soult's Corps partly followed General Holtzendorf and partlyu

threw itself into our left flank, breaking out via Alten Goenne to

Hermstedt. At the same moment Bernadotte's Corps, coming

from Dornberg, appeared on the left flank of General

Holtzendorf and compelled him to retire ...

"it did not appear if it would be possible to hold the

position at Vierzehn Heiligen any longer with so few troops . . . As

the enemy now started to advance, Regiments ZastrowandGrawert

turned ...

"The great superiority of numbers of the enemy was now apparent . . .

There are a number of points of interest in this extract. Some

tell us that the Prussian artillery "fired aimlessly", yet

Marwitz mentions that not only was Vierzehnheiligen "almost

flattened", but also that the very first incendiary shell fired "set it

alight". A number of other extracts below mention the

effectiveness of the Prussian artillery despite the way in which

it was handled. We often hear the reason that the Prussians did

not storm Vierzehnheiligen was that they were "untrained for

village fighting".

Someone appears to have forgotten to remind Hohenlohe,

Grawert and Marwitz of this. Hohenlohe almost had the place

taken with the bayonet and Grawert objected on the grounds

that the battalions were half-ruined by enemy fire, not that they

were untrained for such an exercise. Marwitz, Hohenlohe's adjutant,

did not advise against the Prince's proposal on those grounds.

One wonders where this story of the Prussians being

unable to fight in the villages comes from. The next point is

that for a time the Prussians thought that they had victory in

their grasp. Some historians and writers tell us that the result

of Jena was a foregone conclusion, yet it seems in fact if, even

for a short time the matter was in the balance. The difference in

tactical doctrines ~o not seem to have been decisive. Marwitz

mentions that Grawert argues against going into the village

partly on the basis that the battalions designated for the attack

had been under fire "for two hours". We will later see that

others dispute this length of time and it does not seem beyond

the bounds of possibility that Grawert was exaggerating to

underline his argument.

Finally on this account, it is interesting to note that a major

factor in forcing the Prussians back was the turning of both

flanks of their position at Vierzehnheiligen and the subsequent

threat to their rear.

The report of Colonel von Kalckreuth, commander of infantry

Regiment Prince of Hohenlohe (No. 32) at Jena (printed in Jany's

"Gefechtausbildung", pp. 123ff.):

"The skirmishers of the regiment spurred on by those officers

commanding them stopped the enemy light troops from advancing for

a very long time although they were better protected everywhere by

terrain which was most advantageous to them. It could not be

otherwise, for in this standing battle which we had to endure for

several hours, we had heavy losses of men due not only to the far

more numerous enemy artillery but also due to the skirmish fire.

Despite that, the courage of the men was unshaken and if

circumstances had allowed us to attack the enemy instead of waiting

for his attack, then this courage would never have dissipated. In the

meantime, the former did not occur, there merely came the order not

to advance any further. This lack of movement gave everybody the

opportunity to see the unfavorable turn of events and the disorder

tearing the beaten left flank apart everywhere. Also, the movement of

the enemy cavalry which was beginning to go around our unprotected

right flank and thus into our rear was drawing on the men's attention

and causing despondency. . .

There are several points worth noting here. Firstly, the

skirmishers of this regiment were used but would seem to have been

beaten by the French who were better protected. Yet some writers

claim that "absolutely no skirmishers" were deployed. Other

accounts below will confirm the use of skirmishers by the Prussians

in the fight around Vierzehnheiligen. Secondly, the French artillery

certainly seems to have been responsible for a substantial amount

of the casualties suffered and thus losses were not due just to their

skirmishers. Finally, we get confirmation of the effect of the French

flanking moves which seem to have decided the issue at

Vierzehnheiligen.

Thirdly, for the sake of balance, I now refer to extracts from

Pascal Bressonet's "Etudes tactiques", pp. 179ff:

"During this time the infantry of Grawert's division continued its

offensive march on Vierzehnheiligen ...

"The French, posted in the hedges and enclosures, put up a

lively fire. Their action, like that of the skirmishers spread out over

the plain, along with the cannon of the grand battery and the artillery

of V Corps inflicted significant losses on the Prussian line for which

there was no proper reserve to replace them.

"Grawert's infantry replied to this terrible fire by first throwing out

to the fore their isolated skirmishers, then by employing battalion

volleys and platoon fire, mostly without result despite the skirmish

fire of the French being so effective that Regiment Sanitz fell back

for a moment. it was however reformed in line by Prince Hohenlohe.

"Meanwhile, the Prussian 12pdr. batteries were causing serious

damage in our artillery but without obliging them to cease firing,

although several pieces were dismounted and several caissons

blown up. . .

"Meanwhile, around Vierzehnheiligen, the combat grew in

intensity.

"Wolframsdorf's battery of 12pdrs. had not stopped firing on the

village. But the French were not evacuating it, holding the outskirts

with screens of skirmishers and sheltering their reserves behind the

walls and sheds ...

"Hohenlohe's line however moved closer and closer to

Vierzehnheiligen in spite of the enormous losses it was suffering. Its

fire became terrifying and it was a critical moment, 'the most critical

of the day'says the report of V Corps.

"Marshal Lannes resolved to attack the enemy's left wing ...

"Hohenlohe, seeing the start of this movement, immediately

understood the danger and consequently had his left flank position

altered and formed a hook which was prolonged by the cavalry on the

plateau.

"in spite of the intensity of the fire of Battalions Kollin and

Grawert, of 12pdr. Battery Wolframsdorf and of Gause's half-battery

which was placed in front of Dragoon Regiment Krafft, the two French

regiments succeeded in their attack ...

"But Hohenlohe had sent the Saxon cavalry placed to the north of

Isserstedt and brought back the Kochtizki Cuirassiers with several

squadrons of the Albrecht and Polenz Light Horse. The 100th. and

103rd., still in disorder, were charged by them all . . . The 100th. and

103rd. were obliged to fall back to their starting point ...

"The Prussian Regiment Grawert recommenced its slow march

on Vierzehnheiligen.

"However, this local success by the cavalry decided nothing and

the need to put an end to this long wait was becoming urgent. The

intervention of a fresh reserve thrown on Vierzehnheiligen was all

that would bring about a solution ...

"Judging that time to be the favorable moment for the last effort

he sense necessary, the Prince resolved to have Vierzehnheiligen

attacked with the bayonet by several battalions ...

"Grawert requested him to take a different course ...

"Then, looking at Vierzehnheiligen, judging that a simple

bombardment would not cause the village to be evacuated, it was

decided to follow the advice of the gunners, that is, to set it alight.

The first shell was effective. The French evacuated the first houses

but remained behind shelter in the gardens, along the fences and

hedges. The reserves merely fell back.

"Seeing that the fire was not causing an evacuation, the firing of

incendiary shells was stopped.

"Only the bayonet would have led to a decisive result.

"But at this moment, Napoleon, until then on the defensive,

awaiting the result of the battle fought by Saint-Hilaire and the arrival

of his reinforcements, came to learn that Holtzendorf's Corps was

defeated. At the same time, he saw VI Corps and the Cavalry

Reserve debouching.

"The Emperor passed over to the offensive.

This version coming from an historian on the French General Staff

provides much food for thought. it confirms that Grawert first used

his skirmishers against Vierzehnheiligen, but it would seem that they

were soon driven back. It also confirms that the Prussian artillery

was used to great effect. Of great interest is that it would seem

that at one point the battalion and platoon volleys by Hohenlohe's line

tipped the balance against the French in Vierzehnheiligen although

these volleys appear to have had little effect for most of the time.

However, this moment would seem so crucial that Lanness risked

two of his regiments in a diversionary action to relieve the pressure.

Bressonet confirms Hohenlohe's intention to take Vierzehnheiligen by

the bayonet. it is also apparent that as the artillery bombardment had

not caused the desired evacuation of the village by the French, that

Hohenlohe was again on the point of storming it when Napoleon

passed over to the offensive.

Finally, to a short quote from Houssaye's "Iena":

"It seems that German history exaggerates the length of the stand

by Grawert's division in that position by an hour. . . "

This is a possibility which I think can be considered as all the

German accounts seem to be based on Grawert's estimate.

From all the above, I think it is now possible to glean a reasonably

accurate outline of the events in and around Vierzehnheiligen.

Firstly, the Prussians, about 6,000 men, advanced to within a few

hundred paces of the village. The thin skirmish screen was thrown

out and driven back. The Prussians then engaged in volleys by

battalion and platoon. The artillery of both sides came into play, the

Prussians seem to have inflicted appreciable damage to both the

village and the French batteries, and the French caused severe

losses to the Prussian infantry with cannister fire. The French

infantry remained largely hidden, behind cover, with skirmishers

sniping at the Prussian line and inflicted significant losses with no

great losses of their own. The Prussians did not press the attack

home and storm the village. Although accounts state that they

remained stationary, there seems to have been a slow forward

movement. Marwitz seems to think that about this time, the village was

set alight. Bressonet puts it later and that seems more probable as the

moment was now so critical for the French that Lannes launched

a sortie from the village with two regiments of infantry.

This attack was repelled with great loss and the Prussian

advance continued. Hohenlohe decided to press home the attack and

take the village with the bayonet. Grawert stops him and they wait for

Ruechel to arrive.

Meanwhile, the Prussians would now seem to have set fire to the

village, causing the French to recoil slightly. Hohenlohe is again on the

point of having his infantry move in and capture the village. Finally,

just as Hohenlohe is making this decision, the French turn both his

flanks and threaten his rear. The Prussians waver and the French

take the initiative, attacking and routing the Prussians. It is apparent

that there was a lot more to this battle than a line of Prussian

automata blazing away at an invisible enemy for a couple of hours as

their leadership had no idea what to do.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I would advise people wanting to gain a clear and

objective look at the Prussian Army of 1806 and its role in that

campaign to steer away from Anglo-American writings on the subject

and instead to concentrate on the primary and better secondary

sources on the subject produced by the participants and later by the

General Staffs of the respective armies. A comparison of several

such accounts gives a good overview of the events.

Jany, Curt: Ceschichte der Preussischen Armee (Reprinted

Osnabrueck 1967), esp. Vols. III & IV. Referred to as "Jany".

(1) See THE COURIER, III/5,

III/6, IV/2.

More 1806

My thanks to Major Lawson for presenting his counterargument to the

views I expressed in the series of articles I wrote on the development

of Prussian tactics from the death of Frederick the Great to the end of

the Napoleonic Wars (1).

My thanks to Major Lawson for presenting his counterargument to the

views I expressed in the series of articles I wrote on the development

of Prussian tactics from the death of Frederick the Great to the end of

the Napoleonic Wars (1).

"For this legend, which even today is stuck fast in many heads, the

twenty years of Prussian history from 1795 to 1815 fall into two

sharply contrasting periods as black and white as the Prussian flag. The

years of the Peace of Basle with Revolutionary France were, according to

this view, a period of stagnation and decadence for which the collapse of

1806 was payment, the period from 1807 to 1812 is a time of

courageous reform, regeneration and preparation for the uprising which one

could say occured according to programme and was rewarded with

the victorious Wars of Liberation.

Prussian infantry officers, field dress, 1806. (Kling)

Prussian infantry officers, field dress, 1806. (Kling)

Prussian musketeers in campaign dress, 1806. (from Kling)

Prussian musketeers in campaign dress, 1806. (from Kling)

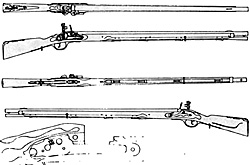

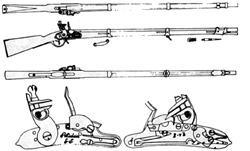

Prussian Musket, 1740/89 Model. One of the several used by the Prussian infantry at Jena. Note the shape of the butt. (With the kind permission of Biblio-Verlag).

Prussian Musket, 1740/89 Model. One of the several used by the Prussian infantry at Jena. Note the shape of the butt. (With the kind permission of Biblio-Verlag).

Prussian Musket, 1809 Pattern. The butt is largely similar to

that of the above. (With the kind permission of Biblio-Verlag).

Prussian Musket, 1809 Pattern. The butt is largely similar to

that of the above. (With the kind permission of Biblio-Verlag).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

German General Staff: Das Preussische Heer der

BefreiungsKriege Q vols., reprinted Bad Honnef 1982). Referred to

as "GGS".

Exerzir-Reglement fuer die Infanterie der Koeniglich

Preussischen Armee. (Berlin 1912). Referred to as "1812 Regs".

Fiedler, Siegfried: Grundriss der Militaer und Kriegsgeschichte

3.Band-Napoleon gegen Preussen (Munich 1978) Referred to as

"Fiedler".

Braeuner, R.: Geschichte der preussischen Landwehr (Berlin,

1863). Referred to as "Braeuner".

Lehmann, Max: Scharnhorst (2 vols., Leipzig 1886-1887).

Referred to as "Lehmann".

German General Staff: 1806. Das Preussische Offizierkorps und

die Untersuchung der Kriegsereignisse. (Berlin 1906). Referred to as "1806".

Bressonnet, Pascal: Etudes Tactiques sur la Campagne de 1806. (Paris 1909)

Jany, Curt: Die Gefechtsausbil dung der Preussischen Infanterie von 1806. (Reprinted Wiesbaden 1982).

FOOTNOTES

(2) See Jany III, pp.185ff.

for details and methods and how they changed since the time of

Frederick. See also Jany IV, pp.22: 'The old Canton Regulation of

1792 did however remain in force until spring 1813.'

(3) The former system of

recruiting foreigners was abolished on 20th November 1807 (Fielder

3, pp.276). That does not mean that the foreigners already in service

were dismissed.

(4) Jany III, pp. 489f f.

(5) GGS 1, pp.351ff.

(6) CGS 1, pp.37.

(7) 1812 Regs., pp.121ff.

(8) See Fiedler 3.

(9) Braeuner I, pp.136ff.

(10) Fiedler 3, pp.149.

(11) Quoted in Jany IV, pp.2 fn.

(12) "Seltsame Schicksale eines alten Soldaten" (Ueckermuende 1850).

(13) "Erinnerungen aus meinern Leben 1791-1810 (osnabrueck 1975).

(14) Quoted in Paret, Peter: Clausewitz & The State, pp. 130.

(15) Quoted in Fiedler 3, pp.41.

(16) Lehmann I, pp.307.

(17) Jany III, pp.432ff.

(18) Braeuner I, pp.256ff.

(19) 1812 Regs., pp.121ff.

(20) GGS I, pp.257.

(21) This essay appears in "Verstreute Kleine Schriften" (Osnabrueck 1979).

(22) Finot: Une mission

militaire en Prusse en 1786 (Paris 1881) pp. 192, 280.

(23) Jany III, pp.468 f n. 114.

(24) See Paret, Peter:

Yorck & The Era of Prussian Reform (Princeton 1966).

(25) 1806, pp.182-183.

(26) Printed in 1806.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. V #3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1984 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com