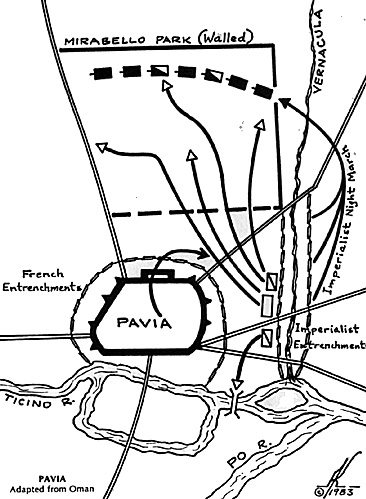

Francis advanced into Italy in midwinter, rapidly gaining back Milan, because the Imperialists had abandoned it due to a plague. The French moved on to besiege Pavia, an Imperial army moved up to relieve it, and the two armies entrenched facing each other across the Vernacula brook. A prolonged standoff ensued, with the obvious problems such inaction brings to largely mercenary forces. The landsknechts of the city garrison were barely kept from desertion, those in the relief force were either leaving or threatening mutiny, Francis' "Black bands" disbanded themselves, and 6,000 Swiss marched off.

As Lannoy and Pescara were about to lose their

army, they accepted Bourbon's desperate plan for a night

march around the French flank. They breached the stone

walls of Mirabello Park, and began to file through (see Fig.

3).

As Lannoy and Pescara were about to lose their

army, they accepted Bourbon's desperate plan for a night

march around the French flank. They breached the stone

walls of Mirabello Park, and began to file through (see Fig.

3).

Francis reacted vigorously with his cavalry and artillery as soon as he saw what was happening. The artillery fired at the breach, where the rear of the Imperialist line was struggling to drag some guns through, and a charge of the French light cavalry completed the rout in that sector. The king himself took the bulk of his gendarmes and charged the Spanish heavy horse in the right center of their formation, quickly despatching them as well.

Unfortunately the French infantry did not account itself as well. The Swiss were slow in forming up and conducted a half hearted charge to no effect. The landsknechts made a better show, but with the French artillery screened, the cavalry committed elsewhere, and no other infantry for support, they were surrounded and overwhelmed. Alencon's right wing needed only a sally by the garrison to convince them things were going badly, causing them to slip away across the river. That left only the gendarmes still in action, now surrounded by Spanish infantry and slowly being worn down. The park provided plenty of cover for arquebusiers to evade cavalry charges and fire at close range. Francis was captured, and most of the remaining captains slain.

The historical lesson of Pavia is supposedly that the day of heavy cavalry is over, and the age of gunpowder has begun. A more realistic interpretation would be that the general who allows an enemy to fall on his flank when not even formed up can expect trouble. Certainly the arquebus proved effective in the open field for perhaps the first time in a major engagement; however the gendarmes performed magnificently once again, as they had done in every battle save one (Novara) in 30 years, and would do again at Ceresole. With reasonable support they may have saved a terrible situation.

This splendid force of cavalry deserves great credit throughout the entire period, not only for their outstanding feats of arms, but also, as Taylor stresses, for their discipline and willingness to take on undesirable tasks. Curt Johnson, in GORGET AND SASH, reports that at Marignano the King's gendarmes formed up in two deep columns and peeled off one rank after another for successive charges, a remarkable feat for the period. Furthermore, Bayard did not have to allow himself to be captured at Guinegate to save his fleeing comrades, nor at Bicocca did the gendarmes have to volunteer for the risky assault on the bridge behind the enemy position-a task for infantry if there ever was one. Although Pavia may not deserve its landmark status in military history, however, it still makes for a most interesting simulation.

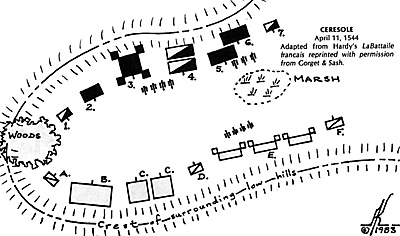

Francis managed to get himself released from Spain in 1526 by agreeing to a humiliating treaty and leaving his sons as hostages. (this loss filled him with such remorse that he leaped on his white charger and cried, "At Last I am King again!" as he galloped away). To quote Oman, "But oaths made under duress are flimsy bords, even to men of a conscientious turn of mode, and Francis, with all his external parade of chivalry, was anything but conscientious." By 1527 the treaty was repudiated and the war was on. The only major open field clash came almost twenty years later at Ceresole (April 11, 1544). This was a traditional head to head fight, far different from those we have looked at (see Fig. 4).

Ceresole contained few surprises-the Spanish routed the Italians, the gendarmes routed the Spanish horse (naturally), and the Swiss (with considerable help from the Gascons) routed the landsknechts. The gendarmes then attacked the Spanish infantry- immobilizing it and keeping it at bay until the Swiss came up to force surrender. It is obvious that we are well into the transition to early modern warfare here. There is little experimentation, the relative merits of various troop types and their roles are well established, and the armies are becoming virtual clones.

From now on armies will be differentiated because one side has cavalry of higher morale or heavier armor, while the other ranges its infantry battalions in deeper formations-a far cry from the uncertainties and tension of pike-halberd vs. gendarme crossbow vs. colunela. Ceresole may have interest for Thirty Years War or ECW afficionaclos, but it is far more structured and predictable than the chaotic clashes of Grandson or Marignano.

With figures available in 15, 25, 30 and 40mm, the splendid appearance of the armies involved, the multiItude of unusual and fairly well documented historical scenarios, and an unusual lattitude of realistic command decisions due to the remarkably wide variety of troops, the true Renaissance deserves more interest than it generally receives. Hopefully these two articles, taken together, will give those whose interests lie elsewhere some idea of how the art of war got from Agincourt to Breitenfeld, and encourage some to give the period a try.

FRENCH

FRENCH

- 1. Lt. Cavalry

2. Monluc's Gascons

3. Swiss Veterans

4. Gendarmes

5. Grison's "Psuedo Swiss" Recruits

6. Italians

7. Archers - Hvy Cavalry

IMPERIALISTS

-

A. Florentine Cavalry

B. Italian infantry

C. Landsknechts

D. Spanish Cavalry

E. Spanish Veteran Inf.

F. Neapolitan Cavalry

S. Swiss

L French Landsknechts

KG King's Gendarmes

C Other French Cav

A Alercon's division

SOURCES

Most of the sources listed after the previous article are also useful for this period. Additionally there are several good primary sources, including the Loyal Servant's History of Bayard, Monluc's Commentaries, and Machiavelli's On the Art of War, The Discourses, and The Prince. Special thanks to Curt Johnson.

More Battles

-

16th Century Battles Introduction

16th Century Battles Marignano Sep 13-14, 1515

16th Century Battles Pavia Feb 24, 1525

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1983 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com