Before descibing a couple of battles in some detail, let me make the disclaimer that battles such as Ravenna, Marignano, and Pavia are inevitably described as "confused" affairs, meaning that we are reaching the age when we have multiple primary sources which naturally tend to conflict with each other. While using Oman for my framework, I shall resist the temptation to play it safe and merely parrot him, but instead include points from other accounts when they disagree. While some of the facts may be arguable, the overall picture should be accurate.

Novara should have been the end of the hopeless French adventures in Italy, but, unfortunately, the following year Louis XII died and was succeeded by the young, brashly egocentric Francis I. At the start of the next campaign season the French were back, spoiling for a fight against all comers, who could have been almost anyone since the French were now allied with their old enemies the Venetians against a more bizarre alliance of the Pope, the Spaniards, and the Swiss. As the Spanish army was currently involved with the Venetians, the French moved against the Swiss, who currently controlled Milan.

The French settled in near the city and attempted to bribe the Swiss to leave, successfully sending off the Bernese contingent (and others) totalling 12,000 pikes, or one third to one half of the entire Swiss force! The Pope's representative managed to precipitate a battle, however, before the rest of the Swiss could decide to leave.

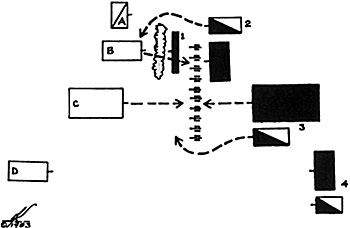

As Francis was in the process of continuing his not unsuccessful negotiations, he was of course surprised to find the confederates charging him, but for once the French were reasonably well positioned. The initial attack, about 4PM is shown in Fig. 1.

The left most leading pike block had its impetus slowed by a frontal cavalry charge and some landsknechts skirmishers positioned across the ditch. They broke through shortly, however, crossed the ditch, captured several guns, and plowed into the French foward division. Eventually their progress was halted by cavalry charges into their left flank and the resistance of landsknecht halberdiers. About this time the scene was repeated in the center as the Swiss Gewalthaufen crashed into the King's landsknechts of the French main battle.

Marignano: The First Day Sept. 13. 1515

Marignano: The First Day Sept. 13. 1515

- A. Milanese Cavalry

B. Vorbut-lucerne, Basel et al.

C. Gewalthaufen - old cantons

D. Nachhut-Zurich, Apperzell et al

1. Landsknecht Skirmishes

2. Vaward-Boubons Cav; Gascon, Basque & French Inf.

3. Main battle - king's gendarmes, landsknecht "Blackbands", etc.

4. Rearward - Alercon's cav, relatively few infantry

5. Venetians - It. cavalry, with heavier following.

If the ditch extended this far it played no part, but the landsknechts had the advantage of support from the elite gendarme companies and the bulk of the artillery. Once again the French line swayed but held, thanks to repeated cavalry charges, and fighting eventually petered out in the darkness.

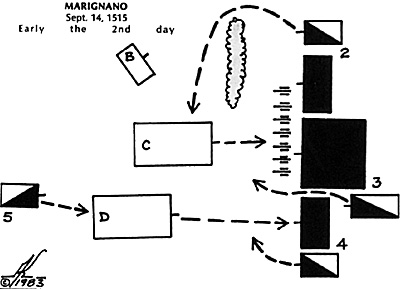

Dawn of the 14th found the Swiss in a highly precarious position perhaps reminiscent of Lee's situation on the third day of Gettysburg. The French had completely consolidated their position, with Alencon and Bourbon drawn in on the King's flanks, and the Swiss had lost their major advantage--the crushing impact of their initial charge. They knew they would be blown apart if they stood still, and ridden down by unopposed cavalry if they moved (the Milanese cavalry had long since gone, having played no part).

The Swiss still tried one last desperate offensive. The left (formerly leading) division was stripped down to a small covering force, while the Gewalthaufen was reinforced for a massive push in the center. After this was underway, and the French had committed all available reserves, the practically unbloodied right hand division was to wheel around into Alencon's rearward division, which would be unsupported, had little artillery, and no defensive works (Oman refers to this as the left-hand Swiss column, which seems unlikely as Alencon was opposite the Swiss right).

The attack in the center did get to push-of-pike for a short period, but the covering force was unable to prevent Bourbon's cavalry from striking the flank of the Gewalthaufen, causing it to halt in point blank range of the guns. The right hand column had reasonable success against Alencon, whose force did not break but was slowly being driven back. Things looked bad for the Swiss, due to their failure in the center, but not hopeless.

At this crucial moment the cavalry of the Venetian army, which had managed to slip away from the uncharacteristically inactive Spanish to Francis' desperate summons, suddenly began to appear in the Swiss rear. The right hand Swiss column, now fully engaged with the French rearguard, was surrounded and annihilated. The Gewalthaufen saw little point in undergoing further unopposed bombardment, and began a remarkably orderly retreat. The heroic spirit of that retreat, and of the Swiss themselves, is well captured in a passage from de Valliere, quoted by Shellabarger:

- "Enveloped in smoke, elbow to elbow, pressing

about their flags, they retired unbeaten, with the same

firmly regular step, heads up, rage at heart, bruised, but

not broken, by the tempest of the French squadrons.

Between them and the highroad to Milan, the Spazzola

canal barred their march and turned them at bay during its

passage. The spectacle was one of terrible beauty. Riven

at close quarters by a powerful artillery while on all sides

swept around them the attacking cavalry, the Swiss

thought only of saving their standards. The sacred colors

are passed from hand to hand, sink in the storm, are

raised and float again, blood-stained shreds, broken

flagstaffs, warm still from the grasp of the dying.

There Moritz Gerber, ensign of Appenzell, mortally wounded, hid in his breast the precious colors before expiring. There fell the three bannerets of Zurich, Jacob Meiss, James Schwend, and the Knight of Escher, but the banner, demy argent and azure, was saved. Saved also was the flag of Unterwalden and that of Basel at the price of the life of John Baer. Around the starred banner of Wallis and the bear of Bern, bodies heap up. Hugo von Hallwyl and Peter Frisching, captains of Bernese volunteers, died heroically. The gigantic Rudolph von Salis, covered with wounds, sank wrapped in the fo/ds of the Grison's standard ... At this final hour, the Swiss, magnified by ill fortune, seemed yet to defy the enemy. Charging the wounded on the shoulders, they left the battlefield with twelve cannon and fourteen captured standards."

Marignano displayed several facets of the developing

post-Medieval tactics. The Swiss concept of drawing

strength from an area of the enemy line preparing a

powerful stroke against it appears almost Marlburian, while

the French employed the modern tactic of using cavalry

charges to drive infantry into squares as artillery targets.

At Fornovo the heavy cavalry had been the whole show. At

Ravenna they still won the honors of the day, but in an

equal partnership with the infantry. At Marignano the

gendarmes were still decisive, but only as a supportive

arm to the infantry and artillery.

Marignano displayed several facets of the developing

post-Medieval tactics. The Swiss concept of drawing

strength from an area of the enemy line preparing a

powerful stroke against it appears almost Marlburian, while

the French employed the modern tactic of using cavalry

charges to drive infantry into squares as artillery targets.

At Fornovo the heavy cavalry had been the whole show. At

Ravenna they still won the honors of the day, but in an

equal partnership with the infantry. At Marignano the

gendarmes were still decisive, but only as a supportive

arm to the infantry and artillery.

Marignano gained the territory of Milan for France for six years, the longest period they were ever to hold it. In 1521 the Italian condottiere Prospero Colonna regained all of northern Italy for the Imperialists in a virtual reenactment of the Garigliano campaign.

In 1522 the horrible debacle of Biococca completed the destruction of the elite veterans of the Swiss army, and inflicted another crushing defeat on their French employers. 1524 brought yet another Garigliano style campaign, most notable for its sorry ending at the Battle of the Sesia, a hopeless rearguard action in which the famous chevalier Bayard was killed by an arquebus shot through the spine. Bayard had commanded the French rearguard throughout most of their numerous routs, from the Garigliano through Guinegate (1513) and into the 20's, and had finally only been given command of an army several days before his death because the incompetent Bonnivet had decided to leave after maneuvering his army into a hopeless position. (Every French renaissance army needs a Bayard d'azur, au chef d'argent ch. d'un lion issuent de gules; au filet d'or en bencle, br. sur le tout* [for heraldry fans] with the banner of a crimson cross of Lorraine on an argent field.)

The loss of Bayard had been preceded the year before by the defection of Bourbon to the Imperialists, and before that by the loss of all the veteran Swiss captains at Biocca. Thus, when Francis decided to personally embark on the tenth French invasion, in 1525, he was without virtually all of his capable commanders. Considering that he was ranged against Lannoy and Pescara, excellent generals aided by Bourbon and Frundsberg, creater of the landsknechts, it seemed likely that the French would be outgeneralled-for a change.

More Battles

-

16th Century Battles Introduction

16th Century Battles Marignano Sep 13-14, 1515

16th Century Battles Pavia Feb 24, 1525

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. IV #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1983 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com