Lest the reader think that unusual tactical situations were limited to the complex terrain of Switzerland, we will now take a look at the initial engagement of the Italian Wars.

Charles VIII of France had decided to acquire his (somewhat dubious) "rightful inheritance" of the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy, regardless of the fact that once he held it he would be isolated from the rest of his kingdom by several hundred miles of unfriendly territory. He moved into Italy with a large and powerful force of gendarmes and mercenary Swiss pikemen and thereby forced the local Italians monarchs to hole up in their castles. The Italian fortifications had not kept up with recent improvements in artillery, however, and

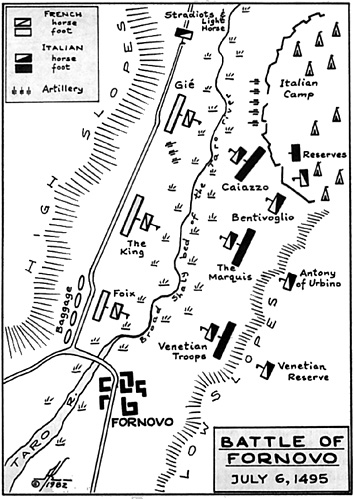

THE BATTLE OF FORNOVO (from Oman, 1937). On the French side, the Marshal de Gie commanded the van, the King and la Tremouille the main body, and the Count of Foix the rear. For the Italians, the Count of Caiazzo led the Milanese, and the C-in-C Gonzaga, Marquis de Mantua was with the center.

The French siege train demolished the Neapolitan defenses in a remarkably short time. The rest of the Italian states, understandably concerned, then banded together to attempt to cut off Charles' return trip. They were faced with a problem, however, in that the logical place for such an attempt would be Appenine passes, but in such terrain neither conclottiere cavalry nor disaffected, ill-trained Italian infantry would be much use against fierce halberd wielding Swiss mountaineers. Still, the Italian captains realized that they were no match for their opponents in the open. They compromised by setting an ambush where the path of the Taro River begins to widen out as it emerges from the mountains, so that cavalry would have sufficient room to charge but an army on the march would have little room to maneuver.

The condottiere captains, skilled in the "art and science" of military maneuver but unfamiliar with the ruthless, bloody melees to which the Swiss were accustomed, came up with a marvelously complicated plan of attack using no less than nine divisions. The idea was to have the stradiots (who were irregular, poorly disciplined, Balkan light cavalry in Venetian service), attack the front of the French column of march and pin the entire army.

After a skirmish with the French van, the stradiots were to move around to the left side of the column. Mean while three Italian heavy cavalry divisions (Milanese, Venetian and smaller states), were to fall on the column's right flank from front to rear. Each division had infanty support, as well as a powerful reserve division which was to charge in support at a given signal. In addition, the Italian artillery was well situated to play on the entire length of the column while the French pieces would be vulnerable and difficult to deploy.

The stradiots did their initial task well, but once they had worked their way around what was becoming the French rear they acted like the bandits they actually were and simply proceeded to plunder the French baggage train. The three front rank condottiere divisions were countercharged by gendarmes and driven from the field in minutes with heavy losses.

The Swiss infantry, who were all located in the oversized forward division, then turned on the hapless Milanese infantry, who had just watched the only effective arm of their force rout past, and cut them down. The reserve Italian cavalry divisions discreetly refrained from getting involved, one captain explaining lamely that he had not received the signal. As Oman wryly remarks, "one would have thought that seeing the division you were supposed to support being driven from the field would have been a pretty good clue that assistance was needed."

The Taro had a flat, shaly bed which the Italians did not figure to present any obstacle. However it had recently rained and the initial cavalry charge lost some of its effectiveness.

Oman gives a total of about 15,000 Italians, including 2400 mounted men at arms, 2,000 lighter cavalry including 600 stradiots, and 10,000 infantry, including a few German pikemen among the usual mass of Italian crossbowmen. He gives the French 9,000 total, with 900 mounted men at arms and 7,000 infantry, including 3,000 Swiss. Harbottle, in similar fashion to his Grandson estimates gives 8,000 French and 34,000 Italians. Of such are legends born.

Hopefully this article has given the reader some ideas for how to realistically create balanced scenarios for Renaissance armies despite their vastly different capabilities. It really is not necessary to think, "Well, I've got 50 gendarmes and 100 Swiss. With the artillery that makes over 2,000 points. Now where do I get 500 Spaniards?" If feedback suggests an interest in such, perhaps there will be a follow up article on the last 50 years of the period entitled, "Now that I've lost my eyesight, my wife, and my job painting up all of these bloody landsknechts. . ."

SOURCES

Kirk, John Foster; History of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Philadelphia, 1868.

Miller, Douglas; and Embleton, G.A. The Swiss at War 1300-1500(1979); and The Landsnechts (1978), Osprey, London.

Oman, Sir Charles; The Art of War in the Middle Ages 378-1515 (1885); and The

History of the Art of War in the 16th Century (1937).

Shellabarger, Samuel; The Chevalier Bayard. The Century Co., N.Y. (1928).

Taylor, A.J.P.; The Art of War in Italy 1494-1529. Cambridge University Press (1921).

Dupuy's Encyclopedia of Military and Harbottle and Bruce's Dictionary of Battles

are referred to for numerical troop estimates.

More Swiss

-

Renaissance Swiss: Introduction

Renaissance Swiss: Battle of Grandson: March 2 1476

Renaissance Swiss: Battle of Morat: June 22 1476

Renaissance Swiss: Battle of Fornovo: July 6 1495

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. III #6

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1982 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com