In the late 17th century, the lands of Habsburg Emperor

Leopold I lay squeezed, viselike, between the "Unholy

Alliance" of the Sun-King's more than metamorphic rising

star and the "Hereditary Enemy", the waning, but still potent

Ottoman Empire. Spurred on by yet another alluring

Hungarian rebellion, French diplomacy, coupled with

aggression on the Rhine, the Sultan (more truthfully, the

Grand Vizier) launched his empire's last major effort in

mainland Europe; the objective, Vienna. We shall use the

campaign and the resulting Siege of Vienna in 1683 as a

focus with which to examine the make-uo of the Ottoman

military machine at the dawn of modern Europe.

In the late 17th century, the lands of Habsburg Emperor

Leopold I lay squeezed, viselike, between the "Unholy

Alliance" of the Sun-King's more than metamorphic rising

star and the "Hereditary Enemy", the waning, but still potent

Ottoman Empire. Spurred on by yet another alluring

Hungarian rebellion, French diplomacy, coupled with

aggression on the Rhine, the Sultan (more truthfully, the

Grand Vizier) launched his empire's last major effort in

mainland Europe; the objective, Vienna. We shall use the

campaign and the resulting Siege of Vienna in 1683 as a

focus with which to examine the make-uo of the Ottoman

military machine at the dawn of modern Europe.

Though suffering major defeats, primarily due to lack of organization on a tactical level, the army of the Ottoman Empire managed some credible victories and was still potent enough to require the Habsburgs to wage a twenty-year war, captained eventually by the great prince Eugene.

ON CAMPAIGN: STRATEGY & LOGISTICS

The Ottoman army was as colorful and diversified as its parent Empire. The Jannissaries, Spahis of the Porte and the Artillery, as in earlier times, still remained the nuclei of the army; supported as it was by a host of auxiliaries and subject races, ranging in ablility from valiant fighters to no more than cannon fodder. Its compostion was still predominently cavalry and mounted infantry.

Ethnically, it soldiers assembled primarly from the Asian homeland aeas, but with Arab and European elements contributing sizable contingents. For the campaign and Siege of Vienna, Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa assembled over 250,000 men, recorded by Jeremias Cacavelas as follows:

The Regular Army and Provincial Bodyguards:

- The Saphis 35,000

Sultan's Jannissaries 25,000

Jannissaries of Europe 12,000

The Artillery & Miners 32,000

Dellis & other fanatics; Guardsmen (incl. retainers) 8,000

The Auxilliaries & Levies:

-

Iraq (feudal estates)** 1,300

Baghdad 14,000

Upper Syria 24,000

Lower Syria 18,000

Asia Minor 30,000

Anatolia 18,000

Pamphylia 8,000

Achaia 16,000

Tarters 14,000

Hungarians 6,000

Vlachs 6,000

Cossacks 6,000

** A token appearance, as the majority would be needed to guard against the Persians, There were besides 250 cannon, 30,000 draft horses and 3,000 camels. Other forces engaged in other theatres would have been the Hungarian rebels and the garrison troops of local Pashas.

In addition the forts of Tata, Papa, and Veszprem each had 500 garrison Jannissaries. Ibrahim Pasha of Buda was blockading Jawaryn with 19,800 irregulars and 7,500 European Jannissaries. Hussein Pasha was before Pressburg with 22,000 local troops in addition to 1,000 Jannissaries and 10,000 Hungarians under the rebel leader Tekeli.

Against this impressive array the Austrian army could muster on paper 80,000 men, organized into 23 infantry, 17 cuirrasier, 7 dragoon, 3 Polish "cossack" regiments, and 8,000 Hussar. However, many of these regiments were still in the recruitment stage or were needed to watch France.

The organization of the Ottoman military machine pinacled in the hands of the Grand Vizier, who, unlike his Imperial counterparts, the princes and Marshals, held ab- solute control. On campaign, the Kaimakan (deputy), Pashas (particularly Buda, Baghdad and Cairo), the Beglarbeys (provincial governors), Agas of the Jannissaries, Spahis and Silhaders, as well as the commanders-of-the Artillery and Engineers could be called to councii to give advice on strategic choices, though they could be vetoed or even prevented a seat on council by the whim of the Vizier. Orders would then be detailed to each of the major Beglarbeys, who could also command troops of provinces not their own, Within each of the groupings, orders would be passed on to lower-ranking Pashas and in the "regular army" to corbachi (soup-carrier), whose closest functional equivilant in the west would be a colonel.

Campaigns were pre-planned with a single objective in mind, usually a major city or fortress. The Ottoman principle of strategy was based on geographic objectives rather than on remaining "in the field" with the purpose of pursuing and destroying the enemy's army. This was due to the organization and supply limitations of the Ottomans, although this was true to some extent of all combatants of the era.

All campaigns originated in Constantinople, which served as the major armory and supply depot for the Empire. There, all the various feudal contingents assembled. The Holy Flag of the prophet would be unfurled and the troops would follow the perennial horse-tail standards tc war (7 tails per standard denoted that the Sultan himself would lead the army; three, the Grand Vizier; and one a Bey; two, a Pasha [except Buda, Baghdad and Cairo - also three].

The state provided supplies only for the "regular army"; the feudal elements and auxiliaries were required to equip and supply themselves (as well as pay a levied tax on all captured booty) for the duration of the campaign year. In addition, being basically a cavalry army, the Ottomans could only campaign when the grass had sprung (depending on nature's goodwill). The Ottomans on campaign were equipped with an enormous amount of superfluous baggage... tents, carpets, silverware, etc., and huge numbers of combatants and non-combatants, all of which must have strained supplies and which when coupled with the horrendous Balkan roads made the Ottoman campaigns one-season affairs, characterized by a tide-like invasion, both psychologically as well as militarily.

With the onset of winter, the feudal element would return home to supervise the harvest and planting of their own holdings' crops, while the "regular army" garrisoned the still hostile frontier. It is probable that a rotational system was used where each year a different draft of retainers would be sent to the front.

The Ottomans possessed swarms of swift, resourceful (albeit undisciplined) light cavalry. These reconnaissance forces woild keep careful watch on approaching enemy forces, while devastating the countryside to deny its forage value to that enemy. The psychological effect on the Austrian army of numerous massacred Christians is obvious.

TACTICS

It was on the tactical level that the Ottoman armies vis-a-vis the new "standing armies" of the west were at their weakest. For it is on the tactical level that the organization, drill, synchrozation, indeed the total absorption into the military arm of state, is founded. This was the sovereign's direct tool for imposing his will, ingraining an immediate obedience to a succession of peop1e in higher ranks, culminating in state-ruler. This regimentation (and the word is justly derived) prevents an army from disintegrating into an unruly mob.

The Ottoman armies were composed, for the most part, of a vast feudal host, subordinate to the various chiefs and depending mainly on personal valor and a certain martial ego to carry their initial charge. These feudal elements of the army would follow their course of action either by personnel involvement or by following their contingent's flag or totem, which, in turn, would follow the landowning "colonel". These, in turn, would receive their orders from the Beys.

A rather basic repertoire of "cresent pincers" and feint attacks would serve as a sense of drill and orientation to action. However, once that leader is dead or bested in personal mellee, there is no one to lead or maintain cohesiveness, as thus an every-man-for-himself attitude prevails and disintegration is a likely occurence. Against Medieval Christian knights and their retainers, the loss may not have been so drastic, as each man resolved his own personal melee. But against 800 men or more reacting as a single body, the result was devastating.

In the regular army, the Jannissaries, Saphis and Topdji were to a certain extent, drilled and organized, probably best in the Topdji and least in the Spahis. The Jannissaries marched in steps, three paces forward, halt, three paces forward, and were accompanied by a military band. These bands could be considered one of the ways organized warfare was developing to transmit orders by their rhythmic messages, keeping the unit "wound up" and running as a single entity. the military bands also served to be psychologically useful as the side (at least in aboriginal warfare) which makes the most noise has a certain edge.

A degree of training and continual communion with a certain set of fellow warriors helped build strong ties of comradeship and reassurance in one's fellow soldiers, and Jannissaries were probably with one particular Orta for life as their heraldic tatoos would testify.

Ottoman tactics were based on fierce enveloping charges, coupled with determined attacks by the awe-inspiring jannissaries and Spahis. If this failed, there was a steady defense of prepared fieldworks, coupled with feint attacks to lure away the enemy's mounted arm.

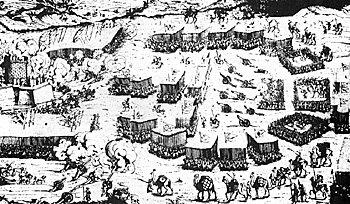

Strong on the offense, the Ottomans could on occasion ride down infantry (though probaly "shaken") and at least force an aggressive melee on the already missile-oriented Christians. the Ottomans' lack of integral cohesiveness, lack of control and the generally undisciplined nature of the troops made it a brittle sword. The old print published in 1566 by Jost Arman and pictured at the beginning of this article shows an interesting battle array. The light cavalry are ready to envelop the enemy flank, the Spahis are in reserve. Note the infantry squares, a precaution against the heavy European cavalry. Pack camels are also seen in the print, perhaps acting as a flank guard, but more probably used to deliver refills of arrows,etc., to the skirmishing cavalry.

More Ottoman Army at Vienna

-

Ottoman Army at Vienna Part 1: Introduction

Ottoman Army at Vienna Part 1: Army Organization

Ottoman Army at Vienna Part 2: Standards and Flags

Ottoman Army at Vienna Part 2: Irregular Forces

Ottoman Army at Vienna Part 2: Christian Foe

Ottoman Army at Vienna Part 2: WRG Army List

Related

-

Turkish Delights: Using the Ottoman Turks in the Napoleonic Period 1795-1815

Using Ottoman Turks on the Wargame Table

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. III #3

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1981 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com