Using Ottoman Turks

On the Wargames Table

Part II

By Wyatt Kappely

| |

"Whatever communications We abrogate Part I, Turking Delight chronicles the history and organization of the Ottoman Army.--RL.

As you've probably noticed, the most prominent feature of the Ottoman Army is the fact that the bulk of its forces are "Irregulars" (tribal, feudal, clannish warriors and fighters rather then formed highly disciplined, regular, professionals trained to fight in tightly drilled formations). It is this irregular feature that the majority of rule sets try to present widh varying degrees of success. Unless you're careful, however, you may tend to look at the disadvantages of being "irregular," and perhaps miss some of the advantages. REGULARS OR IRREGULARS?Most every set of rules that I've looked at agree that the Nizam-i-jedid (Sultan Selim III's "New Order Troops"), the Suvarileri Cavalry, and the Turkish Topiji artillery crews are the only Ottoman soldiers that should be classed as "regulars" and can perform the same range of movements, assume the same formations, and react like their regular counterparts in European armies. What you might miss if you follow these rules to the letter is the fact that there were other Ottoman troops that should be treated as "regulars". In the last issue it was shown that a number of the provincial warlords, in particular Ali Pasha of Janina and Mahomet Ali Pasha of Egypt, sought to incorporate the western model of drill and training into various regiments within their armies. Therefore, when assigning the status of "regular" to units in your armed forces, do not be limited to what is allowed by your rules, feel free to incorporate a greater number of these other "regulars" into your order of batde. MELEEAn example of what I mean can be described by the square: Only "regulars" can "form square" therefore the great bulk of Ottoman infantry is incapable of performing this maneuver. That is very important when one considers what happens to nonsquare infantry caught in the open by charging cavalry. Related to this square issue is the fact that in the Ottoman army, only the "regulars" had bayonets. Bayonets are what convinces any sensible horse that it doesn't want to have anything to do widh that prickly square thing. Bayonets are also the melee weapon of choice for the regular soldier (According to traditional history of the American Revolution our rebel militia lived in fear of the British regulars and their skillful use of the bayonet). In the hands of well trained soldiers, the bayonet is an awesome weapon. The great Russian Suvarov emphasized its use over even musketry. All this might not mean anything when it comes to the Turks when you consider that the average Ottoman soldier came very well equipped to conduct melee, many possessing an inordinate number of swords, spears, pistols, and bits of armor. When combined with their individual courage, these accoutrerments could possibly have given them an advantage in melee over their bayonet equipped opponents. They preferred to come, literally, to grips with their opponents in what they considered an honorable form of manly warfare. William Johnson, author of The Crescent Among the Eagles believes that, for these reasons, the Ottoman irregulars should get some sort of melee advantage over regular troops. Of course, there are others who believe that the reverse should be true. Whatever your decision, a melee advantage either way could be something as simple as a plus or minus percentage modifier applied to the melee result. Related to the cavalry and infantry in square issue, an interesting question was raised by Mr. Johnson. Reflecting on the lack of bayonets and square formations within the ranks of the Ottoman infantry, how did they defend themselves against cavalry? One suggestion was that the huge number of Ottoman cavalry counteracted the corresponding western cavalry. This is doubtful when one considers the lack of quality within the Turkish mounted arm. Nor could it have been the extensive use of fortifications by the Turkish infantry. It probably was the number of melee weapons and armor carried by the Ottoman foot soldiers, combined with their looser formations and individual courage and fanaticism, versus the enemy cavalry's lack of armor (something they discarded after the 17th Century) might have made a cavalry charge against this horde of sword wielding fanatics an iffy proposition at best. This is a judgment call. In the final analysis, the greatest strength that cavalry ha.s against foot soldiers is its ability in provoke fear in the infantry's ranks, causing them to break and run at the first sign of a charge. The greatest number of casualties are not inflicted by cavalry during the fight, but when the defeated infantry begin to run. The reason that the square and the bayonet is so successful is that it gives the disciplined infantryman the confidence to withstand the charge, and promotes fear in the cavalryman's mount. If infantry that is not in square decides to make a determined stand against charging cavalry, then I believe that the cavalry would have a difficult time dealing with them. An example is the famous charge of the 21st Lancers against the Mahdist irregular infantry at Omdurman, an infantry force that had barely a bayonet to their name. The resulting fight did not result in the rout or destruction of the infantry, but resulted in the heaviest loss of life experienced by any unit on the British side that day. So I suggest ignoring any "cavalry versus infantry in the open and not in square" modifiers whenever the infantry in question are Turkish irregulars. The lower Turkish morale values, and the resultant high casualties caused by being defeated in the open should make up for the lack of a melee modifier for the cavalry. Infantry: Irregulars are not really good at conducting formed drill and are best controlled when in column formation. Thus it is generally agreed that irregular infantry should only be allowed to charge while they are either in skirmish or column formation. The skirmishers of course would be subject to the same restrictions administered to their regular counterparts. Also, some sort of restriction should be placed on irregular infantry's ability to maneuver, and as to what formations they can assume. Mr. Johnson recommends restricting the number of facing movements, etc. that irregulars can perform. This is particularly true for those wonderful levy street sweepings, the Fellahin. This can be accomplished by allowing one action (firing, moving, or changing formation/facing) in a turn. In other rule sets, one could just increase the movement cost for each of these actions to reflect the individual levels of training within the various Ottoman formations and troop types. To their advantage, Ottoman infantry should be allowed to charge or counter charge against formed enemy cavalry (something that most rules do not allow infantry to do). The rule set that we use, a modified version of Mike Nemechek's Volley Fire, allows for this, and makes victorious irregular infantry perform a "control check" to see if they go into uncontrolled pursuit after the end of a melee. This works pretty well, causing some very interesting situations. Mr. Johnson also feels that Turkish Infantry should be accredited some sort of positive morale bonus (+5) when they are in the defense (which I must assume means that they are standing there waiting for an attack to hit them) and that they should be afflicted with a negative morale modifier (-5%) when they are actually moving towards the enemy line. This due to the Ottoman characteristic of being more confident in the defense than they are in the attack. The only exception to this, in my opinion, would be those troops classed as fanatics. These fellows ought really to be at their happiest while attempting to close with the enemy. Perhaps they should get a positive modifier morale modifier for advancing, and be negatively affected while sitting around waiting for something to happen. Cavalry: It has always been my impression that too many rule sets place a few too many restrictions on the functions of cavalry. For example, in Empire, dragoons are not allowed to mount and dismount during the course of a game. This despite the fact that they might actually do this as part of their mission. Also, for rules covering the period of 1700-1820, the use of cavalry is greatly degraded by a built in rigidity of forcing formed cavalry that is charged to counter charge or stand and take the impact. I prefer the methods employed in Ancient Empires where almost any cavalry can choose to fall back or evade when charged. Ancient Empires bases each unit's ability to evade upon certain conditions such as whether the unit was in skirmish order, is light cavalry as opposed to heavy, and from which aspect (front, rear, or flank) did the unit receive the charge. I have taken pains to implement a similar system in our rules, and thus far, it has worked. What makes it particularly interesting is that the poorer grade cavalry types, such as the Arabs, the Yoruks, the Tartars, and of course, our friends, the ever wonderful Cossacks (Zaporozhi!) can be used to suck their more forrnidable enemies into carefully laid traps. But most important, it helps you to preserve your light cavalry from being senselessly destroyed in cavalry engagements that they by instinct would have avoided. Ottoman cavalry was notoriously impetuous, and had a

tendency to charge at the least provocation. To an extent, the same might

also be said of their irregular infantty. At Aboukir, the Janissaries

charged out of their entrenched positions to attack the French probably

contributing to their subsequent lopsided defeat.

Most Turkish cavalry gets hit hard by this control check. Mostly because they possess a great number of the features that negatively affect their chances of maintaining control. The attributes of being light cavalry, irregulars, and being equipped with lances, each subtracts 5% from a unit's chance of successfully maintaining control. To make things worse, if any of the units are classified as fanatics, then they are accessed an additional -5% penalty. The beauty of this is that the Turkish player still has some hope of maintaining control of his cavalry and irregular infantry, but is also faced with the fact that their impetuous nature makes them harder to control.

The Ottoman munitions factories (if you can call them that)

were quite obsolete and produced an inferior brand of powder. Also,

amongst the irregulars, the fire discipline was somewhat lax or

non-existent. Therefore, there should be some sort of negative modifier

applied to the effects of Turkish musketry. Empire handles this

by having the Turkish infantry fire at one morale grade below what their

base morale grade would normally allow. Other sets generally have a

negative modifier for all poorly trained infantry (in our set it's a

whopping -25% of your total percentage chance of inflicting casualties),

and designate almost all Turkish infantry as being poorly trained for fire.

This modifier could also be applied to a portion of the Turkish artillery,

most notably the provincial artillery forces equipped with old style,

16-17th Century cannons.

As far as morale goes, the Turks are a mixed bag. The morale

grade variations are as diverse as the nationalities that make up its

soldiers. To try to assign a single morale grade to any particular type of

Turkish soldier, such as the Empire rules assigning all

Sekhans the morale grade of Landwehr, would be a bit erroneous.

So one should feel free vary things just a wee bit.

For example, Empire assigns the following morale values to the

various troop types within the Turkish army:

One thing that most commercial rules agree upon is that

anytime that Russians and Turks meet on the battle field, that the base

morale values of both sides be increased by at least one level as they are

hereditary enemies with a long standing blood feud - both sicles rarely

took prisoners. It has been said that the reason Napoleon's army took so

few Russian prisoners during the 1812 campaign was due to the

Russians having just finished a long war against the Turks, and were out

of the habit of surrendering.

It is said that the Turks would intentionally sacrifice the lives of

their less valuable units in order to weaken and exhaust their enemies.

For many years this policy worked out quite well. Additionally, there

always seems to be a group of individuals willing to be sacrificed in order

that they might contribute to the overall victory. In Islam, those who die

as martyrs facing the foe are considered to be transported to Heaven.

At Omdurman, the Sudanese Mahdists launched charge after costly charge at their British enemies, resulting in massive casualties, without measurable effect. The point is that they kept on coming. I wanted to simulate the same force of men. Brave fellows who would rush madly forward, heedless of casualties, and fired up with religious zeal. And yet, I wanted it to be easy for regular troops to defeat them. The point wasn't that they were suppose to make massive break throughs or such. But that instead, their role is to weaken the enemy, or tie down a segment of his army through means of their persistent attacks - they had to keep coming back for more.

To simulate religiously fanatical units, I use two separate values

to simulate the high morale of the unit and its low melee effectiveness.

This is similar to that used in Empire where various

troops like the Austrian Regular Infantry have a morale grade of

"Conscript" but shoot as if they were "Landwehr". In the case of our

fanatics, we would assign them the morale grade of say "Grenadier" or

"Guard" for morale check purposes, while using a morale grade of maybe

"Trained Militia" or "Landwehr" to resolve melees.

When crossing fields of fire, the fanatics should be capable of

suffering excessive casualties, without failing their morale tests, or failing

to go through with their declared charges. However, the actual melee

combats are generally lost and this is due to the extremely low morale

grades assignecl to the units for melee purposes.

Typically, a Sudanese brigade-sized horde will rush into an

engagement, using its high morale values to ignore its casualties, lose the

melee, yet still inflict some casualties or fatigue upon the enemy. They

should then fall back, quickly rally, then attack once more. Eventually,

even they should get so shot up that they become ineffective. But in

practice, they still should accomplish their job of weakening the enemy

and pinning him down. As far as balance goes, my Sudanese have proven

quite reasonable. Their high morale versus their low melee value gives

them quite a lot of potential. However, because they have no fire arms,

and because they actually lose more melees than they win, they do not

dominate the battle field. This makes them well accepted by the other

players in our group. One important note, these rules for the fanatics

only work if there is provision for casualties to be inflicted onto both

sides in a melee.

As regards levies and fellahin troops, my friend Steve came up with a wonderful idea which he was going to use with his Spanish Guerrillas. But since he has so far failed to organize this rabble, the idea was instead tried out on my fellahin and levies. Based on the assumption that you never know how well your peasant levies are going to fight, we decided that at the beginning of each battle, the actual morale of these soldiers would remain unknown until such time as they were expected to take their first morale test. At that moment, a separate die roll would be made to determine their morale ratings. There is a percentage chance of their being anything from "Untrained Militia" slugs to "Elite" patriots. Of course they have a better chance of being Militia than Elites. But regardless. this morale grade only is applied against morale checks. When fighting melees, like the Sudanese, they use a much lower rating. In this case, "Untrained Militia" as opposed to the Sudanese "Militia" or "Landwehr". This is because no amount of enthusiasm can overcome lack of training. Further, should they ever fail a morale check, they lose forever their higher level morale rating, and become permanent Untrained Militia for both melees and morale checks.

For both the Sudanese fanatics and the levie.s/fellahin, leaders play a big role. For

example, the Sudanese only maintain their "Guard" level morale rating if they are within l 2"

(depends on rule scale) of their leader. Additionally, the leader is inspirational enough to

add a some sort of positive bonus to any morale checks where he is within 3" (depends on

rule scale) of a unit being so tested, and also gives a beneficial modifier for melee to any unit to which he is attached. If he is in a melee, we give him a 25% chance of being killed. Thus, you can get a lot of use out of him, but there is always a risk. Additionally if he is directly attached to any specific unit, he loses command and control over the other units under his command, and they must take a some sort of control test to see if they do what you want them

to do.

As an additional bit each brigade sized force of levies comes complete with a

religious leader who can inspire them to feats of fanaticism. If these leaders (who are in

addition to the brigade commander) are directly attached to a unit of levies, the levies assume

fanatic status and incur all of the bonuses and headaches associated with being so. However

anytime that they participate in melee, there is a 25% chance that these leaders will be killed.

There are a host of other things that can be done. But this should be enough to get

you thinking. What is more imponant is developing a tactical doctrine that will enable your

army to stand up to its opponents and quite possibly defeat them.

"O believers, when you encounter unbelievers in war, do

not withdraw from them. Whoever withdraws, except for changing ranks

or maneuvering in battle, will incur Allah's wrath, and his refuge is

Hell."

Holy Koran, Surah VIII, Verses 15-16.

Okay, all of this sounds great doesn't it? The Turks are reusable. They look wild

and exotic. There are lots of them they possess an oriental charm that is quite impressive. But

how well do these jokers fight? Well, in my opinion, if well led, they fight pretty well, and

this applies equally well whether your opponent be a Suvarov or a Napoleon--just ensure

that the army is handled exactly as it is designed to be handled. If you properly take into account your Turkish army's strengths and weaknesses, while simultaneously employing its time honored doctrinal policies (updated where necessary to meet conditions), and as long as you act as a wily and cunning Turk should act, you will probably be more successful than anyone would

possible expect you to be.

What you have in your Turkish army is a relic from a bygone

era, where life was cheap. Your empire is manpower rich, and being

mainly irregular, your troops lack something in the area of drill and

training. Your weaponry is not far behind that of your opponents, and

your cavalry, as ill disciplined as it might at first seem, is somewhat on

par with that of your enemies' - especially considering the numbers

available to you.

Usually, the Turks outnumbered their opponents and in their masses they can easily wear down an opponent. Ottoman artillery was largely French trained, and as such, wasn't too bad. Empire rates them as Class III which places them on the same level as the Russian

Artillery. In fact, like the Russians, the Turks have always placed a high

value on their big guns. After all, isn't that what they used to batter the

walls of Constantinople? And should anyone ask you, it wouldn't be at

all unrealistic to say that in a pinch, the Turkish siege train could cast its

own guns whenever they might need to do so. I cannot recall of many

Western style armies of the period being able to do that.

Finally, the Turks know the value of a shovel, typically their

engineer corps were every bit as good, and in many cases better than that

of the European powers. Therefore, earthworks and field fortifications

are more of an option with the Turks than with their enemies.

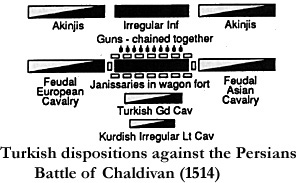

The classic Ottoman battle formation reached maturity in the

late 15th Century and was developed while the Turks were fighting ill

disciplined feudal and Middle Eastern armies. It consisted of a fixed

fortification made from either a mobile wagon fort, earthworks, or both.

Within the fort were contained the army's artillery and the Janissaries. The front of the fort could have Sekhans before it, or else it might be left open to facilitate the formation's artillery fire. The feudal cavalry were divided into two wings and were placed on either side of the fortification. By tradition, the European cavalry were placed on one side and the Asian Feudal cavalry were deployed on the other. Actual deployment depended on the location of the battle. If in Asia or Africa, the Asians had the place of honor on the right. If the fight were in Europe, then the Europeans and Tartarshad the righthand position. To the front of the Sekhans and Feudal cavalry are the irregular light cavalry, i.e. the expendables. Behind the Janissaries are the Sultan's Guard Cavalry, the Suvarileri. In some ways it resembled the Zulu buffalo attack formation, only in reverse.

Under ideal conditions, what is intended is that after being bombarded by the Turkish guns, the enemy attacks the front where they run into the expendable light cavalry. These throwaways engage the enemy for a spell before finally leading them into the massed musketry of the Sekhans. The Sekhans take the handed-off enemy forces and weaken them before falling back and letting the Janissaries and artillery have a crack at the buggers. As all of this blood letting is going on, the enemy is expected to slowly weaken himself until finally being swept in upon by the elite Sipahi cavalry deployed on the flanks. Many Sipahis have been working their way around to the enemy's flank while he has been busy launching his frontal assault upon the wagon

lager.

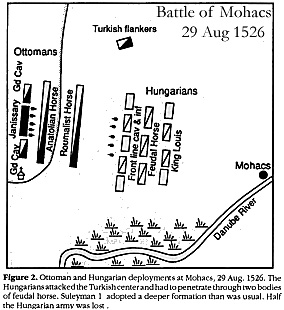

This works well if the enemy develops a bad case of tunnel vision and attacks only your center, such as the Hungarians did at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, or the rout of the Crusader forces at Vama in 1444.

Usually the enemy did something else. At the Battle of Allepo in 1516, the Mamlukes attacked both flanks of the Ottoman army before finally charging the cen ter. But the formation was equal to the challenge, and the cavalry

stationed on the flanks usually succeeded in handling such troubling actions. But these battles were against armies of semi-feudal knights who would charge out at anything, or else they were

brought against less sophisticated Middle Eastern mounted armies, like the Mamlukes and the Persians, who lacked cannon and firearms.

By the beginning of the 17th Century, the European enemies of the Ottoman Empire had become more sophisticated

in their fighting methods. They'd developed disciplined infantry formations supported by artillery and well-trained heavy cavalry.

They largely avoided uncontrolled charges up the middle and managed to retain control of their mounted arms. A detail which

helped them to avoid being surrounded by the huge Turkish cavalry fommations, and which also prevented their attacking -

lines from fragmenting. When the Europeans did attack the center, as did Eugene of Savoy at Belgrade in 1717, the attackers were mainly infantry, and when the Feudal cavalry at-

tempted to launch their flanking attacks, they were easily driven off by the excellent Austrian heavy cavalry. Thus, even as early as the late 17th Century, our classic formation is largely outdated. However, it still has some value, and as a basic example of where to start, the concepts behind it enable us to derive some new tactics and perhaps defeat our foes.

Turkish Tactics on the Table details the tactics to use in miniature battles to win with the Ottoman Turks.

More Ottomans in the Napoleonic Period

Related: Ottoman Army at Vienna

|

In the last issue, we introduced the Ottoman Army, a crazy

rabble of Renaissance-era irregulars trying to combat against some of the

best armies that Europe could field. In this issue, I present a number of

basic rules intended to assist the gamer in accurately portraying the

unique fighting styles and capabilities of the Ottoman soldiers. I discuss

the reasoning behind each rule and how various commercial rule sets

present them, and introduce variations of the presented rules which I

think are important to get the most out of the Turks. Finally, the basic

Ottoman battle doctrine with examples of how they fought, the tactics

they used, and some tricks that may help you win with these wild and

crazy bashibazouks will be discussed.

In the last issue, we introduced the Ottoman Army, a crazy

rabble of Renaissance-era irregulars trying to combat against some of the

best armies that Europe could field. In this issue, I present a number of

basic rules intended to assist the gamer in accurately portraying the

unique fighting styles and capabilities of the Ottoman soldiers. I discuss

the reasoning behind each rule and how various commercial rule sets

present them, and introduce variations of the presented rules which I

think are important to get the most out of the Turks. Finally, the basic

Ottoman battle doctrine with examples of how they fought, the tactics

they used, and some tricks that may help you win with these wild and

crazy bashibazouks will be discussed.

The map at left shows the Battle of the Pyramids, 21 July, 1798, a variation of the classic Turkish formation, with the Mamelukes fortified by the Nile's west bank, Napoleon's "Divisional

Squares" were very effective against the Mameluke cavalry.

The map at left shows the Battle of the Pyramids, 21 July, 1798, a variation of the classic Turkish formation, with the Mamelukes fortified by the Nile's west bank, Napoleon's "Divisional

Squares" were very effective against the Mameluke cavalry.

A good example of this is found in the array used by Selim II at Chaldiran in 1514 against the Persians.

A good example of this is found in the array used by Selim II at Chaldiran in 1514 against the Persians.

In the map at left, Ottoman and Hungarian deployments at Mohacs, 29 Aug. 1526. The Hungarians

attacked the Turkish center and had to penetrate through two bodies of feudal horse.

Suleyman 1 adopted a deeper formation than was usual. Half the Hungarian armywas lost.

In the map at left, Ottoman and Hungarian deployments at Mohacs, 29 Aug. 1526. The Hungarians

attacked the Turkish center and had to penetrate through two bodies of feudal horse.

Suleyman 1 adopted a deeper formation than was usual. Half the Hungarian armywas lost.