It is a socio-political fact that every revolution spawns a counter-revolution. This is true in both the ideological and, frequently, military sense.

It is a socio-political fact that every revolution spawns a counter-revolution. This is true in both the ideological and, frequently, military sense.

Though the Tories of our own American Revolution various Irish "Brigades" and lacobite forces in the British Isles, and the "White Russians" of 1918 are well-known to military historians and wargamers alike, the forces raised by the exiled Bourbons during the French Revolution have received scant attention. The Army of Conde was best-organized and longest-lived of all the French forces in exile during this period (1792-1801).

Following the storming of the Bastille and the de facto imprisonment of King Louis XVI by mobs in Paris, the Duke of Conde and many ardent royalists, including the King's younger brother, the Conte Artois, fled France to Piedmont and ultimately the German Rhine States. Here the emigres waited for the storm of revolution to pass, as it had previously in Geneva. Holland and Belgium.

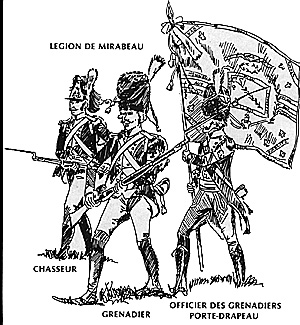

By the winter of 1791, they had established depots to enable three small armies to invade France. These were the Legion Mirabeau, at Yverdon; the Army of Conde, at Mainz; and the Army of the Princes, at Coblenz.

Active financial support for these armies in exile was soon forthcoming from anxious European monarchies and principalities, added to the personal fortunes which the emigre nobility had brought with them from France. The 11% million livres so contributed was, however, soon expended. Salaries alone accounted for over one million livres.

After the Valmy Campaign of 1792, pay was provided by reactionary Europe's perennial paymaster of the period, Great Britain.

Recruits

Recruits for Conde" army were drawn from a variety of sources. Initially, the soldiers in the emigre armies were junior and ser.or officers, with a sprinkling of rank and file (and, in some instances, whole units) from the old Royal regiments of France. These men formed the nucleus of the army throughout its twelve-year history.

Additional French recruits, well-to-do bourgeois, came following the King's imprisonment, and were enrolled in the "Noble" regiments.

High quality troops were recruited from among Swiss and German mercenaries. These were either incorporated into existing units or formed newly raised regiments under the auspices of wealthy royalists. One such was Cardinal Rohan, who raised a legion bearing his name.

The French provinces of Alsace also provided a small, but steady influx of recruits, as Conde's army often quartered there.

By 1797, the majority of recruits were Bavarians, Italians, Austrian deserters and French Republican prisoners-of-war. Needless to say, the quality of the army suffered and the desertion rate rose accordingly.

The Army of Conde's first military action occurred during the Valmy Campaign of 1792. Here, under the overall command of the Duke of Brunswick (who personally despised the emigres), the Allied armies (Prussians, Austrians, Hessians and Royalists) moved into France. The various emigre leaders predicted a general uprising in "liberated" territory, expecting that the various French fortresses guarding the road to Paris would open their gates to the invading Allied armies.

They found, however, a genuine feeling of "patre en danger" and a mistrust of the exiled nobility accompanying France's ertswhile enemies, which prevented the expected enthusiastic revolt. The Valmy Campaign ended in disaster for the Prussian Army, whose soldiers died by the thousands of dysentery.

Though the actual culmination of the campaign ended in a short-lived, if violent cannonade, the Republic had survived and gained both the military and psychological offensive, which would last for the next seven years. The various emigre corps were confined to various sieges during the 1792 campaign. Failing at Thionville, but succeeding at Verdun, with the aid of Royalist sympathizers in the fortress.

Other Uses

The Prussians tended to distrust the emigre units, preferring to use them as "covering forces", but the Austrians under Wallis and Clayrfalt established the custom of employing the emigre units in the vanguard, supporting the various Austrian light troops.

At the conclusion of the Valmy Campaign, all the emigre units with the exception of Conde's, were disbanded. The continued existence of Conde's army was due to: firstly, Conde's ardent and forceful personality (he was once placed under arrest by Brunswick for impertinence) devoted to continuing in the military sphere his cause of successfully reestablishing a Bourbon king in France; secondly, the army was firmly established in the sympathetic Austrian camp at Strasbourg, where support for the Bourbons was forthcoming from the Alsatians.

The following year, 1793, the Army of Conde saw action in Wurmser's Rhine Campaign, again fighting as the advanced guard at the battles of Neuphaty, Steinfeld and Hagenbach. At the time, a minor reorganization took place, with several of the German mercenary regiments entering Dutch service.

1794 was a quiet year for Conde's force as they were stationed on the Rhine front and the severe active campaigning occurred in Flanders. Conde, during the lull, expanded and reorganized all the regiments and legions. The original units of the army were organized into a CORPS ANCIEN or 1st Corps of some 5,000 men. The 2nd Corps, or CORPS NEUVEAUX, consisted of four new infantry regiments of emigres, a German mercenary regiment, four cavalry regiments and two independent squadrons of dragoons and hussars. All regiments of the CORPS ANCIEN were now organized along Austrian lines. The Legion Mirabeau (or the Black Legion) passed to Roger Damas after Mirabeau died of fever.

Active Campaigning

Active campaigning came again in 1796 as the Army of Conde fought in the advance-guard of

Archduke Charles' Austrian Army. The campaign that year in Bavaria went extremely well for the

Hapsburgs, as the Archduke defeated the French at Amberg and Wurzburg. Conde's army played a

distinguished part in the pursuit of Morbeau's French army through the Black Forest. Conde was also responsible for the secret negotiations leading to General P: negru's defection, leaving the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle temporarily leaderless.

Active campaigning came again in 1796 as the Army of Conde fought in the advance-guard of

Archduke Charles' Austrian Army. The campaign that year in Bavaria went extremely well for the

Hapsburgs, as the Archduke defeated the French at Amberg and Wurzburg. Conde's army played a

distinguished part in the pursuit of Morbeau's French army through the Black Forest. Conde was also responsible for the secret negotiations leading to General P: negru's defection, leaving the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle temporarily leaderless.

After the victories of 1796, the following year saw the fortunes of the Army of Conde at the lowest ebb. With Bonaparte's victories in Italy, Archduke Charles had gone there, leaving the Austrian Army in Germany under the command of the less-capable General Werneck. Werneck's army was crushed at Neufeld on April 18 by General Hoche. On the same day, Archduke Charles signed the armistice of Campo Formio.

With the cessation of hostilities between Austria and France, the Army of Conde was left without a sponsor. Fortunately for Conde, Robert Crawford, a British envoy, negotiated passage for Conde's army to Russian service, providing money and 1,100 remounts for royalist cavalry. The emigre corps moved to Poland on July 22, losing two-thirds of the force to desertion when the destination became known.

Russian Division

1798 was another year of reorganization as the Army of Conde was officially established as a Russian Division, directly responsible to the Tsar. To augment the Conde's strength, a Russian infantry and cavalry regiment were seconded to the division.

Moving from Galacia in 1799, the new division joined Suvarov's Russian Army for that general's brilliant Italian Campaign. The emigre division distinguished itself further during this and the following advance and retreat in Switzerland. Conde's unit was responsible for defending Constance from Massena. Facing two French infantry divisions and a cavalry division, they defended the city long enough to enable Suvarov to extricate his army without being outflanked. The Tsar, disgusted at Austrian lack of cooperation, pulled out of the coalition and the Army of Conde was again set adrift.

Luckily, the Austrians were back in the war with a vengeance, and Conde's men, still in Russian uniforms, re-entered Austrian service in Germany. Here they participated in the campaign against Moreau's Rhine Army and fought reasonably well in the decisive French victory at Hohenlinden. This new defeat and the drive towards Vienna, coupled with First Council Bonaparte's victory at Marengo, finally drove Austria from the war.

British Service

The remnants of Conde's forces were taken into British service and given new uniforms. Several emigre regiments entered Austrian service and were numbered with the regular Austrian line regiments. These included the 12th Cuirassieur and two regiments of light cavalry. The remaining units were sent to the Mediterranean and stationed at Malta, where, along with other Royalist units in the British service, were designated as the Royal Army of the East.

A general pardon from France to all emigres in 1801 and a general winding down of hostilities, leading to the Peace of Amiens in 1802 effectively dismantled the Army of Conde. By 1803 they had been formed into the Chasseurs Brittanique and fought in the Peninsula Campaign, again in their traditional role as light infantry, until 1814.

It would not be until 25 years after his intitial exile that Conde would find vindication for his Bourbon masters on the field of Waterloo.

Miniaturists

Though there are no figures produced specifically for the Army of Conde or, indeed, the French Revolution overall, most units of Conde's army can be created by converting with paint existing figures from other ranges, notably Mini-figs' American Revolution range and, in 15mm, Ral Partha's Napoleonic range.

Thus miniaturists interested in placing a unit more exotic than, say, the redundant Imperial Old Guard or Royal Scots Greys on the wargame table may now do so. Though period purists may balk at the idea of using French Revolutionary figures in a Napoleonic wargame, I feel that the potential to educate other players into new eras is worth the historical crossover.

The French Revolution, as perhaps most 18th century warfare, has been largely ignored by wargamers, overshadowed by the color and grandeur of the Napoleonic Wars. Yet, except for Napoleon's sole innovative employment of divisional squares against enemy cavalry in Egypt, he, like all of his contemporaries, used tactics (and that is what miniature warfare is primarily concerned with) developed and established during the preceding French Revolution.

As applicable to wargames, I would treat the units of Conde's Army in terms of effectiveness as follows:

| Legion Mirabeau (Dames) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Morale | Melee | Fire |

| Light | 2nd | 1st | EL |

| Noble Cavalry | |||

| Line | 1st | 1st | - |

| Chasseurs Noble | |||

| Light | 1st | 1st | EL |

| Couronne Cavalry | |||

| Line | 1st | 1st | 1st |

| Hohenlohe Regiments | |||

| Line | 1st | 1st | 1st |

| Rohan Infantry | |||

| Light | 2nd | 2nd | 1st |

| Nouveaux Infantry Rgts. | |||

| Line | 1st | 1st | - |

| All Hussars & Chasseurs | |||

| Light | 2nd | 2nd | - |

| Russian Service | |||

| Line | 1st | 1st | 1st |

| Austro-British Service | |||

| Light | 2nd | 2nd | 1st |

Where Morale, Melee, and Fire ratings are indicated as EL (elite), 1st (rated as regular line units), and 2nd (rated as poor quality mercenary or militia units). These are only general observations as the Napoleonic rules will vary in their handling of these points.

Alternatively, players may classify units of Conde's Army as Austrians, and as Russian troop types, 1797-99.

For painting conversions (i.e., taking a figure of approximate likeness and painting it in the correct uniform colors), I recommend Minifig AWI 20,32 for the Legion Morabeau infantry and, in 15mm, any Bavarian Napoleonic infantryman. Any French infantryman of the American Revolution period will do for the bulk of the pre-Russian service infantry and the "German Regiments", any Prussian or Spanish Napoleonic infantry in bi-corne will do. The French Napoleonic Dragoons will serve well for any Dragoon units and Lauzon's Legion Cavalry figures makes a good hussar in Mirilton.

For organizational purposes on a wargame table, I would organize the units in Austrian Napoleonic fashion.

SOURCES

The most exhaustive and scholarly work on the Army of Conde is Vimcomte Grouvel's Les Corps de Troupe L'Emigration Francaise, Vol. 2, L'Armee de Conde. It gives a general overview of the army's history, recruiting, campaigns and devotes an entire chapter to each unit, exploring history, strengths, organization, uniforms, etc.

Also useful (and in English) is Jacques Godechot's The Counter-Revolution: Doctrine and Action, 1789-1804. This details the history, political, social and military, of the various Emigre groups. Conde and his army are given considerable space and detail.

The Austrian Official History of the Valmy Campaign, printed in German, is useful for maps, organization and orders of battle.

More Conde

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier Vol. 1 #2

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1979 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com