The Flemings continued their offensive campaigns. In 1304 they besieged Tournai, albeit unsuccessfully. In the summer, Philip the Fair tried to take Flanders again. He raised a large army and invaded by way of Tournai. The Flemings broke the siege and drew off, offering him battle, but only in positions so formidable that even the most reckless of the French dared not attack. The French became discouraged, and of course, this was not the type of happy war they were used to. Negotiations were entered into from August 14th to 16th, but to no result. The Flemings then advanced to another position not quite so formidable as the others they had occupied.

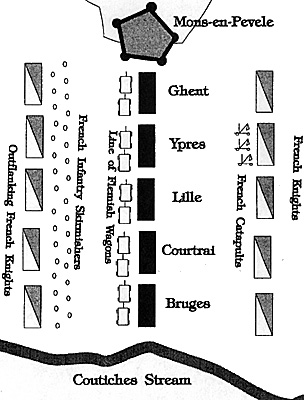

Battle was joined south of Mons-en-Pevele. The Flemings took up a strong position between the village of Mons-en-Pevele and the Coutiches brook, and so close to the French that they could not retire with ease. The ground sloped down to the brook from the village. They drew up their formation in line and protected their rear by a line of wagons guarded by light troops. The Flemings also strengthened their front by the use of pavis and large shields. These were not handled individually, but meant to be stuck in the ground and stood behind, as a crossbowman would do. There were about 12,500 to 15,000 Flemings. Their right was commanded by Philip of Chieti. The men of Ghent were under John of Namur. William of Julich was with the men or Ypres, and the men of Courtrai and Lille were under Robert of Nevers. John De Renesse had been killed two days earlier in Holland.

The battle began with the usual skirmishing of archers. The French were aided by several small catapults under the Count of Bouillon. The Grand Master of the Crossbows, Thibault de Chepoix, moved up to close contact with the Flemings. The other French battles were commanded by the Count of St. Pol, Gaucher de Chatillon, Charles of Valois, Louis of France, and the Dukes of Brittany and Burgundy. The French began an outflanking maneuver, surrounding the Flemings. The French then charged their cavalry which was to the front of the Flemings. However, it was only a feint designed to drive the archers back into the Flemish pike line. The Flemish crossbowmen at this time had the bizarre tactic of cutting their bowstrings and dropping their weapons to take shelter among the pike and goedendag men.

The real blow was to be given by the bulk of the French cavalry which had encircled the Flemish line on both sides and attacked the rear. Meanwhile the French light troops were sent forward to ply their arrows against the Flemings (who could not fire back). Some of the Flemish archers now took heart, and those who had not disabled their crossbows began to fire on the standing French. Several volleys drove the French back from the Flemish center and right. Meanwhile the Flemings on the left (without bows) launched a counter-attack drove off the French knights, and captured the catapults. They put them out of action, and retired to their former position. The French resorted to the more or less futile tactic of trying to get the Flemings to break formation so they could cut off and destroy small groups of them, but to no effect.

While this was going on the bulk of the French knights and infantry attacked the line of wagons to the rear and were summarily beaten. All the French who managed to get into the wagons were slaughtered. Sometime about noon part of the French noticed that the Flemish camp in Mons-en-Pevele was relatively undefended and they attacked, took it, plundered it and took no further part in the battle.The day had been stifling hot and both sides now were exhausted. Only the troops near the stream could drink. Negotiations to end the battle and reach a truce were begun, but they came to nothing. Just before sunset the Flemings decided to attack all along the line.

The French light troops tried to block this but were driven from the field. The French army was taken completely by surprise, and many of the French Knights fled. The Flemish left wing however did not advance. The center and right began to drive the French from the field, and almost captured Philip. In fact, Philip's horse was killed just as he mounted it, and he had lost his sword. He defended himself with a large battle axe that "a butcher" (we assume from the French foot) had given him. The king tried to mount another horse, and it was killed as he did so, and the knight who gave it to him was killed also. The third time he attempted to mount a Flemish knight gave the horse such a blow with his goedendag that the horse bolted and carried Philip from the field. <>Reform and Counterattack

With the king out of danger, some contingents of the French Knights reformed and attacked the now disorganized and separated Flemings. William of Julich's band (by now only 700 stood with him) perished to the last man under attacks from all sides. The rest of the Flemish army took and plundered the French camp (which had a considerably better class of booty than their own) and then retired to their original position, trumpets blowing and flags flying, and picked up their scattered comrades on the way. The next day they retired in good order.

While technically the Flemings were defeated they had withdrawn in good order and were not ridden down by the French Knights. In the Middle Ages, any battle in which the infantry were not slaughtered was something of a victory. Losses were about even. The French had still failed to win against the solid Flemings. The Flemings had shown themselves able to carry the action to the enemy though they clearly did not like to do so. For all their cavalry, crossbows, light troops, and catapults, the French had been unable either to press home an attack or stand against the infantry.

While they held the field they could rightly claim a victory, but it was without doubt that the French had been badly handled, and very close to disaster. Three hundred French nobles had fallen, along with about 1,000 other troops, and 2,000 Flemings had been lost. Philip must have been impressed with that arithmetic. In June 1305 the Peace of Athis was signed. Robert of Bethune, the son of Guy of Dampierre, was given official recognition of his rights by Philip and allowed to return. He accepted the terms of the peace which surrendered to France the "castelries of Lille, Douai and Bethune. In addition a heavy war indemnity was imposed, and the towns had to demolish all their fortifications and restore in all their rights and properties the cursed Leliaert exiles.

It was evident that Robert of Bethune had consulted only the interest of his own principality. The causes of the dynasty and of the people, united during the struggle, now diverged. The commons, who had been carefully excluded from the peace negotiations, obstinately refused to submit. The war began again, and eventually Robert of Bethune, dissatisfied with his treatment by the French king, joined the rebels. The war continued without any great battles. Eventually a new and definitive peace was made in 1320.

It did not last long. The returning Leliaerts, like the French Nobles of the Restoration had "Remembered everything and forgotten nothing". The French did not cease to meddle in the affairs of the county. Revolt brewed up again in 1326 when the weavers of Bruges again revolted and established a true revolutionary government. But the Flemings of 1326 were not the Flemings of 1302. A generation of war and civic division had seriously weakened the communal armies. Further, the feudal nobility did not come forward to help them, and there were no leaders of the calibre of William of Julich or John of Renesse.

More Flanders

-

Flanders Introduction

Flanders Revolt

Battle of Courtrai: July 11, 1302

Battle of Arques: April 4, 1303

Battle of Mons-En-Pevele: August 18, 1304

Orders of Battle

The Flemish Style of War and Bibliography

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #74

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com