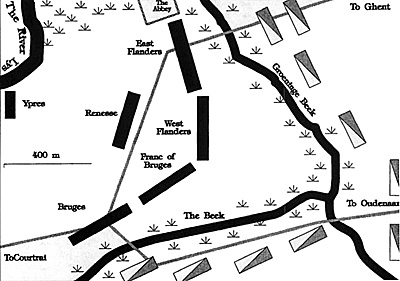

The first battle, Courtrai, took place as a result of French attempts to relieve the Flemish siege of Courtrai citadel. The Flemings had taken the town, but the citadel, built on an island on the River Lys, resisted them. The French moved up to its relief and first tried to take the town, but failed. They then moved to confront the Flemish army which was drawn up on commanding ground outside of Courtrai, sealing off the citadel. The Flemings had placed themselves in a position of great strength, though not without danger. The illustration shows the general terrain forms of Courtrai as it might be modeled for a table-top battle, and is taken from Verbruggen's The Art of War in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. Immediately off the left hand portion of the map are the steep slopes of the Hoge Vigjver, a branch of the river Lys, and the walls of the town of Courtrai. The river Lys, a wide, deep, unfordable stream flanked by extensive marshes, curves around to cover the Flemish left on the top edge of the map. The ground slopes steeply down to this river, and the Abbey shown is on this sloping ground.

To the front of the Flemish position are two streams, the Groenigen Beeke, and the Beeke, also with marshy banks. They form natural obstacles to any advance. A slight slope up from the brooks actually places the Flemings on a shallow ridge. The Flemings were therefore on excellent defensive ground, but were in some danger because retreat from such a position was impossible. The formation of the Men of Ypres faced the citadel and prevented any sally by the French.

The French deployed facing the Flemings across both brooks. An important fact, especially when modeling the battle for the table top, is that the brooks were not so difficult as to be uncrossable, but too difficult to fight across. Further, the French archers could not fire effectively on the Flemings until they crossed the brooks. Obviously this made them a serious obstacle, and, as it transpired, a deadly trap.

The Flemish insurgents had about 11,500 men, mostly all communal infantry with a few knights. The knights fought dismounted among their communal brethren. The Flemings were fearful, dispirited, and apprehensive; after all, the reputation of the French Knights was at its height. The Royal army appeared outside Courtrai on July 8. The French disposed of 2,500 knights, the flower of the French chivalry, and about 2,000 other men at arms, and the rest low quality infantry. The senior French leaders did not want to attack, but most of the rest of the nobility, eager to punish the upstart weavers and glovemakers, did. Raoul de Nesle pointed out the grave dangers which threatened the knights once they were fighting on the far side of the brooks, especially should they be called upon to retreat. Jean de Burlats, Grand Master of the crossbows, hoped to harass the Flemings with his light troops, in order to inflict such great losses on them that they would have to give way, and the knights could then pursue and break them. Godfrey of Brabant thought it wiser not to attack at all, but to make the Flemings stand all day in the hot sun in their heavy equipment without food and drink. They would be so exhausted that they would not be able to fight the next day. The younger nobles would, however, have none of this.

Quite different instructions were given across the way. Guy of Namur, William of Julich, and John of Renesse, commander of the reserve, addressed the troops. John of Renesse, explaining how he was to rush to the help of the long battle lines, gave this advice: "Do not allow the enemy to break through your ranks. Do not be afraid. Kill both man and horse. 'The Lion of Flanders' is our battle cry. When the enemy attacks the corps of Lord Guy we shall come to your help from behind. Anyone who breaks into your ranks, or gets through them will be killed." They also forbade the taking of booty, and that anyone who did so, or who surrendered or fled would be killed at once. No prisoners were to be taken.

Fighting broke out between the crossbowmen of both sides before noon. The Flemings slowly gave way, and the French crossbowmen advanced, followed by their knights. The French crossbow fire was only marginally effective, but the French nobility, eager to fight, did not wish to wait for it to take effect. The crossbowmen were ordered to withdraw, although it is also likely that Robert of Artois did not wish the crossbowmen to cross the brook and engage the Flemings alone.

An interesting question arises about these brooks. How wide were they? It is not necessary to actually measure them (if they still exist at all). Verbruggen notes that several sources say the French crossed the brook as quickly as possible so as not to be counterattacked by the Flemings. Some horses missed their jump or stumbled, others refused and had to be forced to jump. Knights fell from their saddles into both brooks, but on the whole the crossing was successful. A horse can only jump a space of about 12 to 15 feet, and since the front hooves of the horse cannot be on unsteady ground at the beginning of the jump, we must deduct from that distance about six feet, so we're talking about a space of nine feet. This means that the brooks could not have been wider than nine feet.

Further, this distance must be decreased by the necessity of the horse landing on firm ground on the opposite bank. Thus, the brooks could be at the most only five to six feet wide. Sources mention that knights fell off their horses, but they do not mention that anyone drowned, so they could not have been very deep. That the banks were probably soft and marshy is without doubt, but it is interesting that even a minor obstacle like this could form such an impediment to cavalry.

Charge

Once across the brooks the French knights charged. Now comes the interesting part. Verbruggen and others mention the standard "ear-splitting noise" of the impact as the French charged in on the wall of pikes. Yet this cannot be. If the wall of pikes held firm, the French cavalry would have been impaled upon them and fallen into a struggling mass of skewered horses and riders which would have formed an even greater obstacle to the further onslaught of the French than the ordered wall of pikes had been. Further, it would have made as great an obstacle to the Flemings when they later advanced. The battle, would, in fact, have been over. Yet the sources also mention that Godfrey of Brabant knocked down William of Julich and hurled his banner to the ground, but was then brought down and killed.

Obviously they had penetrated to hand-to-hand range, so it must mean that some parts of the line had held firm, and some gaps must have opened up in the pike wall. These gaps were probably made, not by wholesale routs, but by small knots of men becoming confused, or unsteady. Perhaps they faced wrong to meet a suspected danger, perhaps they timidly took a few steps back. The point is that the "ear-splitting din" the sources speak about is probably not from the initial impact, but from the subsequent hand-to-hand fighting phase, where the clash of metal on metal was added to the shouts and screams of men and horses. On the other side, the French, not hurling themselves blindly upon the pikes, and where the pikes had stood firm, were probably jostling around, seeking an opening, and making almost as much noise as if in a real melee. In short, poetic license may be at work once again.

The battle raged all up and down the line. The Flemish left resisted unbroken. The center, where the Franc-De-Burges were stationed, was probably the weakest, because here the line bulged out, and it was no doubt more difficult to maintain order. Here they slowly gave way, and John of Renesse led forward the reserve to push the French back. Then, they went over to the attack!

Then the French in the center were driven back and the whole Flemish line advanced. The French knights were pushed back almost to the brooks. Had the French been forced into the brook they would have been defeated, or so reasoned Robert of Artois, who led his reserves against the Flemings. But he only succeeded in checking the advance for a moment, and even worse, compacted his troops already in the fray. The French, unable to advance or retreat, now could not even defend themselves, and hampered by the swampy ground were cut down in droves.2 Artois was killed and with his death the French army began to disintegrate. The slaughter at the brooks was tremendous and the French broke and fled. For the loss of a few hundred Flemings over 1,000 French knights and over 2,000 French infantry were slain. The victors amassed considerable booty, including five hundred golden spurs and many banners. These were preserved in the church of Our Lady in Courtrai, from which the French stole them eighty years later after the battle of Roosebeeke.

More Flanders

-

Flanders Introduction

Flanders Revolt

Battle of Courtrai: July 11, 1302

Battle of Arques: April 4, 1303

Battle of Mons-En-Pevele: August 18, 1304

Orders of Battle

The Flemish Style of War and Bibliography

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #74

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com