T. Taylor Earle in the Advantages of Height (see The Courier Number 67, pages 29-30) discussed the morale and tactical advantages derived from a higher position. but there is much more to height than the advantages gained from the ability to strike down an opponent from above. the most important comes from the advantage of perspective and command.

There are a number of features of command that depend directly on the commander's ability to see the battlefield. They include direction of the battle, the issuance of orders and the making of plans. All of these require some knowledge of the enemy's positions and dispositions. An unseen enemy is hard to defeat.

Almost every serious Napoleonic wargamer remembers the story of the Old Guard at Waterloo being surprised by the sudden appearance to their front of the British Guard Grenadiers, the surprise and sudden volley unnerved the Guard and they scampered away and with them went the whole Imperial French army and the dreams of Napoleon. Earlier in the battle Marshall Ney with the bulk of the French cavalry blindly charged after the retreating British Army only to bounce into a mass of British squares located on the reverse slope of the ridge. The French heavy guns were unable to fire on the squares because the British were on the reverse of the ridge.

If only commanders could see through trees, troops, smoke, and hills, how much easier command would be and how quickly they could avoid defeat or snatch victory's laurels! Our wargamers seldom face the dilemma, they can see the whole battlefield from on high.

Omniscient Positions

From omniscient positions high above the battle field with complete orders of battle and definitive knowledge of every unit our foe has on the battlefield we are more troubled by the roll of the die than the composition of the enemy's line or the placement of his reserves. We see them well from on high. We can avoid the enemy strength and strike at his weakness. With such conditions can we really claim to simulate any Napoleonic battle?

Our club in Augusta recently reenacted the grand battle at the village of Waterloo for a large crowd at Barnes and Nobles bookstore. The battle was a master piece of fine terrain and beautifully painted figures. The rules, Napoleon's Battles, played well on the twenty foot by seven foot area. Yet from the start, the French had the advantage, they knew the location of every unit on the field and the strength of each. The French crashed forwardin a mad effort to smoother the Allied force to their front which they did in seven turns, though the battle lasted several more turns, the issue was decided well before the patient Prussian players arrived in force.

The issue was never in doubt for two reasons, first the Allied order of battle and dispositions were known to the French players (the British players knew the French Order of Battle too but they were in no position to hamper its success) and secondly, the French could observe over the hill to see when and where the Allies moved their reserves. The Order of Battle problem exists anytime a group attempts to re-fight an historic battle accurately so this article will deal with the matter of visibility on the battle field.

The ability to see the friend and enemy and tell which is which is important at all levels of command. Battalion commanders need to see the units to their front and the units to their flanks. There are few things that a battalion commander could do on his own without the careful coordination and permission of their brigade commander. The brigade commanders had to see not only their own subordinate units but past those units to the front and the enemy.

At the other end of the chain of command is the army commander who has to track his own forces and commanders and see as much of the enemy as possible. Unlike the brigade and battalion commanders the Army commander could move along the line to change his perspective. He must also rely on the eyes of others and the reports they sent their commander. The good commander also had to know his enemy and the lay of the land. But because the commander will always have incomplete knowledge of the enemy he will have to use his own intuition to determine how the enemy commander placed the opposing force. Yes, there is always guess work in command.

Matter of Geometry

Command and control is a matter of geometry to some extent. Direct line of sight is a straight line. This is obvious even to the dullest wargamer but there are ways for a field commander to "bend" his line of sight.

The first and most obvious is by reports from subordinates or staff officers sent out to see for the commander. These reports take time to travel to the commander and the information they contain can be distorted by the skill of the observer. But there are other ways that the line of sight can be bent.

In dry weather, the movement of large bodies of troops and equipment generates dust, which can be visible for miles. The dust clouds can show movement and direction as well as the location of an unobserved force. An astute commander can even tell the size or type of unit by the dust clouds that surround it. The wind can effect the use of dust for spotting purposes. On the other hand, commanders can find the dust of their own forces masking the enemy and his movements. There are ways to generate dust other than the movement of troops such as localized wind gusts. Some commanders have used units to generate dust to draw the attention of the enemy away from other movements.

Noise

Noise is another sight bender. If a force is stationary the noise produced by a moving enemy may be heard for good distances. The wind can often carry sounds for miles. Again, the movement of friendly forces will mask enemy noises. Marshall Grouchey heard the guns of the battle of Waterloo fourteen miles away and in the era of Napoleon there was less background noise than there is today and the noise of battles traveled for miles. Again artificial noise can be generated in an effort to confuse the enemy by creating dummy units.

There are other ways to bend line of sight such smoke from encampments or fire lights in the darkness. These can also be used to deceive for example George Washington used camp fires to escape from the British in December 1776. But, in reality seeing the enemy directly is always the best.

Commanders wanting the best view of the battlefield had to seek high ground. Topography played a key roll on most Napoleonic battlefields. Position was critical to good command decisions both for both visibility and direction depended on the commander's line of sight.

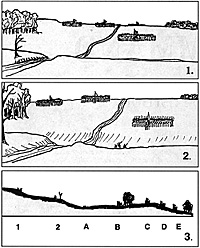

In the view of a commander standing on position 2 (Figure 2) are the skirmishers in location A, and units B and C. Units D and E are out of sight. Although he can see the skirmishers, if the commander at position 1 ordered the commander at position 2 to attack the closest enemy unit they would perhaps be seeing different units as "closest". Likewise if the commander located at position 1 ordered an artillery unit to fire shot at the farthest unit on the right the unit would fire at unit B instead of unit D as the commander had intended.

Balaklava

At the battle of Balaklava Lord Lucan ordered Lord Cardigan to attack the guns, they were both looking at different batteries. From his position Lord Lucan could see things that Lord Cardigan could not and the result was a misdirected charge. Position and line of sight are important. [1]

Commanders need to walk the ground where their units are posted to see what their subordinates can see. A good Napoleonic general always checked to see what the ground held for his subordinates. This is the reason why Napoleon rode along the lines before the Battle of Waterloo, this, and lifting morale of the soldiers by allowing them to see him.

In both drawings, Figure 1 and Figure 2, neither commander can see the unit in location E, see Figure 3. This unit is behind the ridge and thus called behind the reverse slope.

Blind spots could exist on what appeared to be a level field, a small hollow of depression as little as ten feet deep could hide an infantry unit. Wellington's reverse slope stratagems were designed to keep units out of harm and out of sight of the opposing commanders. He employed this stratagem at Waterloo.

If visibility was important to Army and Corps commanders it was just as important to brigade and battalion commanders. But these commanders faced other challenges as well.

Even though topography's role was important to the battalion and brigade commanders their position on the field and in the units was critical to their ability to control their units and influence the local battle.

The horse was an important feature of effective command. The horse provided the commander with relief from the fatigues of the march; a clear rested head on top of its commander's shoulders was important to the success of the unit as was the unit's position. The mount also provided rapid mobility to the commander allowing him to move between units and to positions of vantage and influence within the unit's formation. The steady mount also allowed the soldiers in the unit a clear view of their leader standing erect and resolute in the face of the enemy. This, by the way, also made the commander a better target for that same enemy; it was good thing therefore that the smooth bore musket which most soldiers carried was inaccurate. The last thing the horse provided the commander was a better view of the battlefield. While mounted, an officer could see over his units and into dead spaces to its front.

Commanders, who for whatever reason were dismounted, faced a series of difficulties. Commanders on foot in front of their units could not be seen by the majority of the unit's men. Nor could the commanders influence the action from the front other than a forward movement. (see Figure 5).

If the unit panicked a dismounted commander had a great deal of difficulty even rallying single soldiers much less a whole unit. (see Figure 7 below). [2]

By seeking the high ground on horseback the commander could increase his effectiveness and control of the battle. Because so few positions offered visibility they became sought after on the battlefield. At the battle of Waterloo both commanders sought the best vantage points for the battle. Wellington on the ridge behind La Haye Sainte and Napoleon on the ridge near La Belle Alliance. from his location Wellington was able to observe most of the French dispositions. From his position Napoleon was able to see only about half of the British and Allied formations.

More Perspective

Figures 1, 2, and 3 show two different perspectives of the same battlefield. Figure 1 is the view as seen by a commander standing on position 1, (see Figure 3 - a side view of the battlefield). The commander at this position can see units B, C, and D but not the skirmishers in location A. Nor can he see unit E behind the ridge, even though position 1 is higher than location E. These units are in "dead space" for the commander at position 1.

Figures 1, 2, and 3 show two different perspectives of the same battlefield. Figure 1 is the view as seen by a commander standing on position 1, (see Figure 3 - a side view of the battlefield). The commander at this position can see units B, C, and D but not the skirmishers in location A. Nor can he see unit E behind the ridge, even though position 1 is higher than location E. These units are in "dead space" for the commander at position 1.

The mere six foot of elevation greatly enhanced the commander's view of the battlefield and allowed him to see over and past his own units when he was behind them. The mount extended the line of sight for its rider. It also lifted him up to be a mobile rally point for his men. (see Figure 4).

The mere six foot of elevation greatly enhanced the commander's view of the battlefield and allowed him to see over and past his own units when he was behind them. The mount extended the line of sight for its rider. It also lifted him up to be a mobile rally point for his men. (see Figure 4).

Difficulties

Difficulties

Commanders on foot behind their units could not see the field to their front nor could they exert much influence on the mass of men to their front. (see Figure 6)

Commanders on foot behind their units could not see the field to their front nor could they exert much influence on the mass of men to their front. (see Figure 6)

In the case of a mounted officer, leadership from the front was easier if more dangerous because the men in the unit could see the mounted officer and follow. (see Figure 8 below). A mounted officer also had an easier time when it was necessary to rally or steady a unit from behind its ranks. (see Figure 9 above).

In the case of a mounted officer, leadership from the front was easier if more dangerous because the men in the unit could see the mounted officer and follow. (see Figure 8 below). A mounted officer also had an easier time when it was necessary to rally or steady a unit from behind its ranks. (see Figure 9 above).

The use of flags and guidions also served the purpose of providing a rally point for the unit and an indication to its soldiers of the next activity, preparatory commands.

The use of flags and guidions also served the purpose of providing a rally point for the unit and an indication to its soldiers of the next activity, preparatory commands.

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #72

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com