When you consider that neither had what could be called a dominating terrain feature, the ability of Wellington to hide a major portion of his force demonstrates just how important even a slight terrain obstruction could be.

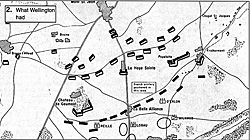

When you consider that neither had what could be called a dominating terrain feature, the ability of Wellington to hide a major portion of his force demonstrates just how important even a slight terrain obstruction could be.

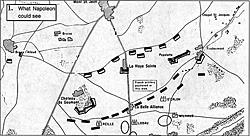

Large What Napoleon Could See" map (slow: 82K)

Napoleon, the aggressor at the battle of Waterloo, had to be in a command position that allowed him to see not only the enemy but his own troops and at the same time be able to project command influence across the battlefield. Wellington, on the defensive, positioned himself where he could see the enemy and his forward units. From his elevated position he could see over the ridge behind him and they could see him as well.

While Napoleon across the low valley could only see the forward units but not those on the reverse slope. Wellington could call forward his reserves or relocate them without allowing the French to see them.

While Napoleon across the low valley could only see the forward units but not those on the reverse slope. Wellington could call forward his reserves or relocate them without allowing the French to see them.

Large What Wellington Had" map (slow: 87K)

A mere twelve feet of elevation hid the units behind the ridge. (see map 1, "What Napoleon could see" and map 2, "What Wellington had").

Besides the lay of the land, topography , towns, forests, farm buildings, hedges, and other man made features could obstruct a commander's view. In the compressed streets of a village or town commanders could see little more than the street in front of them. If a unit occupied a village the commanders as low as battalion lost control of their units in the maze of houses, courtyards, hedges, and fences. This factor alone goes along way to explain the absence of urban fighting on a large scale in the Napoleonic wars. Indeed, Waterloo is marked by three sustained battles for buildings each of which seemed to be a battle in and of itself.

Problem Units

Another problem commanders faced trying to control their units in battle include the units themselves. Friendly units could pose limits on the line of sight in two ways. First, the units themselves could physically block the line of sight. Second the fire issued by units could generate smoke that blocked the line of sight not only for the commanders above but for the officers and men in the unit.

Smoke produced by black powder was thick and heavy. It clung to the ground around units unless the wind carried it off or rain dampened it. Drifting smoke could screen an attack or confuse an advance. Smoke could reduce visibility to less than 25 yards on a still day reducing fire effectiveness and covering unit movements behind the line.

Since weather has been introduced as a topic - rain, fog and snow or combinations thereof can limit visibility and command and control. Precipitation can also affect rates of fire. Most rules sets take weather into consideration but few make it as limiting as it could be. Distance itself can also limit a commander's ability to identify units. At Waterloo Napoleon hoped against hope that the dark columns he saw advancing on the right of his army were Grouchey coming to his aid. Instead they were the black coated Prussians coming to save a worried Wellington.

Seeing an enemy was only half the problem, exactly who did the commander face? Were they Italian militia or the Old Guard. At a long distance every unit looks the same, as they get closer or move quickly or slowly a commander could tell if they were cavalry or infantry and only when they were within a few minutes march could he tell the quality of his foe.

There are a vast number of Napoleonic rules on the market and some address these features discussed. Some because of their scope, are only slightly concerned with a commander's ability to influence the battle due to line of sight and terrain. Napoleon's Battles assigns a commander a command radius and limits commanders outside of the radius to their initiative. Others such as Old Trousers by Howard Whitehouse use both to activate commanders. The best and most complicated command and control is found in Legacy of Glory by Matt and Doug DeLaMater but although the writers reward the player who puts a commander on terrain with good visibility they do not address dead space and hidden units.

Limited Visibility on the Tabletop

The problem of simulating the effects of limited visibility on the game table can be difficult to overcome. But overcoming them can make the game much more interesting. There are a number of ways that players can simulate command problems they include the obvious use of umpires but there are other methods. One is to let one player place his units as blocks of wood on the table and allow the other to find out what is what by maneuvering to contact. Under each block the units are described and the identity is revealed when the enemy "makes contact." Even when this is done by both commanders it does not deal with dead space and other features of command.

An alternative is to use one color of block for both sides and for all types of units. Both players label the blocks and assign one unit to a block. The unit's identity as well as its type are kept secret. As units come into a certain range which depends on visibility and other factors it is replaced by a block which denotes its type, blue for infantry, yellow for cavalry and red for artillery for example. When it gets closer to the enemy the actual figures are placed on the table and the blocks removed. Dummy blocks can be used at both ranges, more at the unknown type range than the type range. Units masked by front line units can be represented by blocks.

Only command figures located on high ground should be allowed to identify the second rank and have the blocks replaced by units. The "second" rank of units and back can be dummies, players can use a fixed number of dummies, I recommend one for two real units for the unknown type blocks and one for four at the known type blocks.

You can make the blocks from a one by two inch (1x2) board cut into two inch lengths and painted the appropriate colors. I recommend white for unknown types and blue for infantry, yellow for cavalry and red for artillery. You can use yellow for artillery and cavalry if you like since at a distance they both appear mounted units. You may also want to represent formation, you can stand a block (unit) on edge to represent a unit in column and lay it flat to indicate one deployed. Large units can be represented by two or more blocks.

Dead Space

Dead space is easier to talk about than play on the table. Empire used a system that created obstacles in the paths of units out of thin air but did not deal with dead space in the sense of a hidden unit. Dead space almost requires an umpire, most rules sets assume that both sides used good reconnaissance before the battle to gather such information. Most of the time dead space has little effect on large battles as the space is too small for the scope of the game and could even be considered to be "included" in the possible outcomes on the combat tables. (You know, that really odd result that has the Imperial Guard rout!). Believe it or not, its a whole lot more fun when you don't know what your up against.

NOTES

1. As a soldier I frequently had to correct my Sergeants and Lieutenants who sited fox holes while standing rather than by getting down on their bellies and siting them with what the soldier could see from that position two meters lower. It is truly amazing what a difference just five feet make in what you can see. Try it some time.

2. Any resemblance between the dismounted commander and the editor of The Courier is very deliberate but inconsequential to the information presented.

Perspective

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #72

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com