To be wounded in the days of yore. The din of musket fire and booms of

cannon slowly replaced by murmuring and moaning, the white smoke of burnt

powder giving way to dark storm clouds. There will be hours, perhaps days, of

parched throat, shivering cold, and throbbing pain while lying on a hard bed of dirt

and weeds. For companions there are the dead and dying.

To be wounded in the days of yore. The din of musket fire and booms of

cannon slowly replaced by murmuring and moaning, the white smoke of burnt

powder giving way to dark storm clouds. There will be hours, perhaps days, of

parched throat, shivering cold, and throbbing pain while lying on a hard bed of dirt

and weeds. For companions there are the dead and dying.

The fate of the wounded is often a mystery in the narrative of an 18th century battle. They are usually treated as anomolous members of the hazy group known as casualties or losses. One hears of peasants murdering and robbing the abandoned wounded after a battle. More often it was the camp followers of the victors robbing the wounded of the vanquished, for after battles entire units (depleated ones) were left behind to guard and help the wounded. Woe to those who would be caught killing the disabled, for a ball between the eyes awaited them.

The story of how the 18th century military dealt with the massive trauma emergency which presents itself after a battle is worth exploring. Practices were developed to cope with injuries on a scale which civilian doctors would be unable to comprehend.

There has been a wide range of views concerning the military medical branch,

from the Duke of Marlborough, who was fairly enlightened in such matters, to men

such as Colonel Walton, who stated 200 years after Marlborough that the medical

branch as well as the religious branch were unnecessary.

[1]

It should be quite obvious to anyone that the medical services save lives, or as

Donald Monro pointed out to King George III in 1764, the preservation of troops is

of prime importance, so that new recruits don't have to be drawn up. After all,

recruits cost money. [2]

In addition, competent medical people help raise morale.

[3]

The saving of France during the seige of Metz in 1552 is attributed to the resolve

given to the defenders by the presence of the surgeon Par6.

The addition of hospitals to a wargames army will add realism to campaigns and

lessen one's losses. Simple rules can be drawn up, some of which will be discussed

later, to implement the usage of a wargames medical branch.

A LITTLE ABOUT WOUNDS

Crude is the perfect word to describe the treating of wounds in the eighteenth

century. The basic way to take care of a major wound to the limb was to amputate.

Wounds were cleaned with brandy then packed with greasy plasters gust after

Trafalgar, one naval surgeon stuffed a wounded seaman's empty eye socket with

oakum, but he survived). Bleeding was done liberally for sickness and after

operations. Physicians would sometimes hold bottles of blood to the light to

diagnose a patient's problem. All operations were performed without anesthesia. All

wounds became infected after operations, one reason being that the same

unwashed instruments were used from patient to patient. Thus puss oozing from the

sutures was considered a normal step in healing, however, if the infection happened

to be tetanus or gangrene, the patient was in for deadly trouble.

Open veins were sutured, specialized bone saws and scalpel were used, and

screw tourniquets were employed. Incredible as it may seem, many of the above

methods were a great improvement over previous ones. The sixteenth century

surgeon simply used an axe to amputate, and cauterised the wound with a red-hot

iron, or a bit of lighted gunpowder if a strong fire wasn't available.

Even more men would have died without the amputations. Gas gangrene would

have caused their bodies to rot before their eyes. Crude as it was, military surgery

was better than nothing. In fact, the quicker and more often amputations were

performed, the greater were the chances of survival. Amputating immediately was

called primary amputation. It reduced chances of bad infection and the patient was

already in shock when it was performed. Waiting a day or more was called

secondary amputation. More limbs could be saved this way by waiting to see if the

amputation absolutely needed to be performed. Unfortunately, this increased the

likelihood of gangrene and exposed the patient to secondary and often fatal traumatic shock. Each type

had it's school and there was quite a bit of debate between them.

[4]

MEDICAL ACTION: BLENHEIM AND FONTENOY

In order to give the wargamer a taste of medical action, two famous

engagements have been chosen: Blenheim and Fontenoy. The bloody battle of

Blenheim was fought on 2 August 1704. The Duke of Marlborough, commander of

the allies, had selected positions for all of the hospitals before the battle had

begun. In the ensueing bloodbath, the allies lost 4,500 killed and wounded, of whom

670 of the dead and 1,500 of the wounded were British.

[5]

The French and Bavarians lost 12,000 killed and 14,000 wounded, with 14,000

more missing, [6] of whom 11,000 were taken prisoner.

[7]

Marlborough entrusted sergeants from every regiment to collect the wounded.

Some of them were eventually stored in tents captured from the French.

Marlborough also ordered that casualties from both sides would receive attention.

Last but not least, a large marching hospital was brought up from the rear.

After the battle, all of the surrounding country had to supply wagons on pain of

death. Most of the wounded were eventually removed on these wagons to the

general hospital at Norlingen, and many were still being treated there in September.

All left at the onset of winter were moved away, many eventually back to their

regiments.

The battle of Fontenoy was fought on 10 May 1745. The British lost 4,000 men

and their Hanoverian friends lost 2,000 [8] , while the

French lost 4,000.

[9]

The severely wounded were collected at the Chateau de Brufford, and 1,200 of

the allied wounded there had to be left in French hands when the allies were forced

to give up the field. DeSaxe, the French commander, asked the British to come and

pick them up.

The Duke of Cumberland, commander of the allies, sent 105 wagons along with

many medical people in response; but the French kept the wagons and offered no

aide to the wounded. In a barbaric fashion, the British surgeons and wounded were

robbed of their valuables and all the surgical implements, For three days the

wounded had to lay there, the surgeons doing what they could without their supplies.

Finally, the wounded were thrown into wagons and driven to Lille and

Valencinnes. It was a miserable trip for them because of the way the wagons jolted

over the rough roads. At last the British surgeons were released, and when

Cumberland found out what had happened, he flew into a riotous fury. At Lille, the

civilian surgeons treated the wounded allies much better, and the townspeople

bestowed every kindness upon them as if to make up for the poor treatment they

had received.

At both Blenheim and Fontenoy, an advanced three-tiered system for taking care

of the wounded was utilized. Emergency treatment was given right on the front lines

by regimental surgeons and mates, which usually entailed stopping massive bleeding.

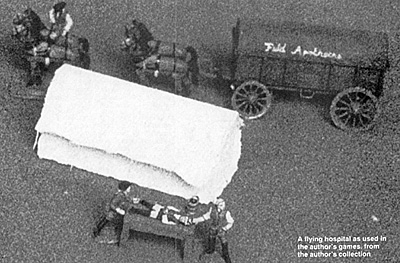

Flying, or marching hospitals with beds and staffs were located just beyond cannon

range, where most primary amputations were performed. Difficult cases, and

operations finished at the flying hospitals were moved well to the rear to some kind of

general hospital which was located in the nearest town. Muscicians, N.C.O.'s and those

escaping the fighting would transport wounded to these aid centers.

Hospitals for Your 18th C. Army

Back to Table of Contents -- Courier #58

To Courier List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by The Courier Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com