The first Russian operation of the war with Turkey came on

November 4, 1914. Four destroyers dropped 240 mines outside the

channel, while the battleship squadron shelled Zonguldak.

The first Russian operation of the war with Turkey came on

November 4, 1914. Four destroyers dropped 240 mines outside the

channel, while the battleship squadron shelled Zonguldak.

Ekaterina II (Svobodnaya Rossiya)

The Goeben, accompanied by the Turkish gunboat Berk and her larcenous crew, sortied to attack the Crimea in hopes of drawing the Russians away from the coal harbor, then searched for their enemies without success. Meanwhile, the Russians ran across three unescorted Turkish troopships and sent them to the bottom.

A week later, the Russians repeated the operation further to the east. The squadron swept along the coast, shelling Turkish coastal towns and searching for more transports. Once again, the Goeben steamed for the Crimea, now with the Breslau. This time the Russians responded to the threat, and the two squadrons clashed within sight of the imperial palace at Yalta.

In a sharp 14-minute, short-range encounter, the Russians claimed 14 hits on the battle cruiser, one of them serious. That was the only actual hit, to one of the secondary batteries, but it came on the very first Russian salvo, killing twelve Germans and shocking Souchon. A fire set off the ready ammunition, and only a petty officer's quick reaction kept the magazine from exploding.

The Goeben, in turn, badly damaged the Russian flagship Evstafi. Souchon told his emperor the Russians shot very well; he told his wife they shot very badly. Had the two Turkish predreadnoughts been along, he told his wife, they would have been lost.

On their return, the Germans also stopped two Russian schooners and captured their crews. Interrogation revealed that the October 29 raid had spread wild rumors through Russian ports, including stories that two German battle cruisers were at loose in the Black Sea.

Reluctant to face the Goeben with only four battleships, Vice Admiral Andrei Augustovich Eberhard ended battleship support for attacks on the Turkish coast for the remainder of 1914 while the flagship underwent emergency repairs. While Goeben and various smaller units escorted convoys along the Turkish coast, Eberhard's fleet continued its aggressive ways with smaller ships. Minelayers laid several new fields outside the Bosphorus, while an attempt to block Zonguldak's harbor with old steamers failed when the commander panicked and scuttled them in deep water.

The Russian battleships continued to operate on the other side of the Black Sea despite Eberhard's caution, as the Breslau's crew discovered on December 24. Having already damaged a Russian freighter in a night attack, lookouts sighted what appeared to be a large steamer in the early-morning mist. Pulling to close range, they found to their horror that they had attacked the Russian battleship Rostislav. Slipping away with her greater speed, the Breslau headed south, fighting a brief action with Russian destroyers along the way, to unite with the Goeben on Christmas Day.

Northeast of the Bosphorus the battle cruiser struck two mines from the new Russian barrier, laid in deep water where German experts said mines could not be placed. One detonated on each side of the ship, killing one sailor and causing the ship to take on 600 tons of water. German shipbuilders' practice of intensive internal subdivision saved the ship, and she limped back to Constantinople.

Souchon had a serious problem. Turkey had no dry dock capable of servicing the battle cruiser. Improvising, the Germans placed coffer dams around the holes and finally managed to patch them, but the Goeben stayed out of action for four months.

The German and Turkish light cruisers could not take the Goeben's place, and Eberhard moved quickly to take advantage of the new balance of power. Russian sweeps destroyed dozens of coastal sailing craft, the backbone of the Turkish war economy. Harbors at Zonguldak and Trabizond received special attention from the battleship squadron, and two of the pre-dreadnoughts even shelled the Bosphorus lighthouse. Seaplanes from the carrier Nikolai got into the act as well, bombing Zonguldak.

Russian troops gathered in Odessa for a landing on the Bosphorus to complement that of Allied troops at Gallipoli. Though the operation never came off, the transports and their cargo presented a tempting target, and the Turkish cruiser Medjidieh, famous for raiding Greek commerce during the Balkan Wars, attempted a daring dawn raid on the harbor. She struck a mine and sank in shallow water. All the crew were rescued, but the Russians raised the ship, repaired her and renamed her Prut in honor of a minelayer sunk in Souchon's October attack.

German and Turkish eyes were focused to the west, where huge fleets of pre-dreadnought battleships arrived to bombard the Turkish fortresses at Gallipoli and Kum Kale guarding the entrance to the Dardanelles. A row of 20 mines dropped by he Turkish minelayer Nousret claimed three Allied battleships, and German submarines soon arrived to drive off the rest of battleships and claim two more.

A Turkish destroyer sent yet another to the bottom in a daring torpedo attack. British submarines now tried to even the score, slipping through the Dardanelles with its tricky currents, minefields and submarine nets to terrorize Turkish shipping on the Sea of Marmora. One submarine sank the ancient Turkish battleship Messudieh, launched in 1874 and used as a harbor guardship, and another actually torpedoed and sank a transport moored alongside Constantinople's naval arsenal.

When the Gallipoli landings began, Goeben still lay under repair. The two Turkish pre-dreadnoughts moved into the Sea of Marmora together with the Turkish destroyer flotillas for a desperate surprise attack on the Allied fleet as it exited the narrow channel into the Sea of Marmora. The furious Turkish defense of the small peninsula, led by Mustafa Kemal, made the suicide mission unnecessary, but the presence of a huge Allied army so close to Constantinople put a certain urgency over operations in the Black Sea.

In early April the Goeben re-entered the Black Sea, destroying several Russian steamers and surviving a brush with the Russian battleship squadron. Now that he knew the Goeben was back, Eberhard set a trap for the Germans.

On May 9, the small armored cruiser Kagul landed troops at Eregli, about 100 miles east of Constantinople, and shot up the town. Goeben sailed out to retaliate. By the time she arrived, the Russians were gone, so she headed stayed at Eregli overnight to allow all the Russians to return to Sevastopol, as had been their practice.

When she returned to Constantinople the next day, the Russian battleship squadron and a dozen smaller ships were still waiting outside the entrance to the Bosphorus. The battle cruiser eventually eluded the Russians with her superior speed, after damaging three of the five battleships, and safely returned to Constantinople.

The action seems to have stunned both sides as they awaited the outcome of the Allied attack at Gallipoli. Russian destroyer raids continued, while Russian submarines took part in an operation to transfer the new dreadnought Imperatritsa Mariya from the shipyard at Nikolayev to Sevastopol.

The attacks on Turkish coastal traffic began to take a serious toll. By May, 1915, after slightly more than six months of war, one-third of all Turkish merchant shipping was sunk or captured, and Turkish industry had little hope of replacing it.

With the arrival of the new Russian dreadnought, more than a match for the Goeben except for her speed, the balance changed again. Two of the older pre-dreadnoughts were relegated to secondary duties, but the Russian battle squadron now had an even greater edge in firepower and another clash with the Goeben seemed inevitable, especially when a second dreadnought, Imperatritsa Ekaterina II, joined the fleet in December, 1915.

The only clash between the Goeben and a Russian dreadnought

came shortly afterwards. The battle cruiser, escorting a single collier,

spotted what appeared to be a sailing ship on the horizon and sped off

to investigate. At a range of ten miles, the unknown ship opened fire,

dropping its first salvo 500 meters from the Goeben and the second 200

meters away. Goeben turned and ran from the enemy, the Imperatritsa

Mariya, and escaped without injury.

The only clash between the Goeben and a Russian dreadnought

came shortly afterwards. The battle cruiser, escorting a single collier,

spotted what appeared to be a sailing ship on the horizon and sped off

to investigate. At a range of ten miles, the unknown ship opened fire,

dropping its first salvo 500 meters from the Goeben and the second 200

meters away. Goeben turned and ran from the enemy, the Imperatritsa

Mariya, and escaped without injury.

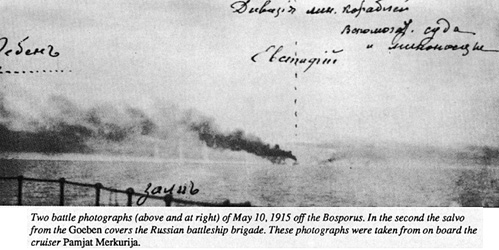

Two battle photographs (at right) of May 10, 1915 off the Bosporus. In the second the salvo from the Goeben covers the Russian battleship brigade. These photographs were taken from on board the cruiser Pamjat Merkurija.

Goeben's captain, Richard Ackermann, asked Souchon to request some submarines from home to

hunt down this new opponent.

Goeben's captain, Richard Ackermann, asked Souchon to request some submarines from home to

hunt down this new opponent.

1916 Landings

In early 1916 Eberhard's fleet helped support a series of landings on the Caucasus front using a new type of assault ship pioneered by the Russian navy. Several shallow-draft minelayers were rebuilt with a bow ramp, allowing attacking troops to storm directly onto an enemy beach.

In April 1916 Breslau encountered Ekaterina II and several destroyers near Trabizond. Slipping into the darkness, the German cruiser was challenged by the Russians. Her commander ordered his signal officer, Lt. Karl Doenitz, to repeat the same signal back. Mollified, the Russians turned away. Relieved, the commander ordered Doenitz to wish their "comrades" a safe voyage. The message sent, Doenitz could not resist adding a line of his own: "Kiss my ass."

The Russian reply tore a huge chunk out of the Breslau's bow. Laying on all possible speed, the Breslau headed for Constantinople through a hail of 12-inch shells. The Russian destroyers did not attempt to pursue, saving the cruiser.

A few days later, another Russian landing drove the Turks out of Trabizond. Using the landings to envelop the Turkish seaward flank, Russian forces pushed the Turks steadily backward. Two divisions now landed west of Trabizond, and the Russian predreadnoughts moved their base of Batum for closer support.

Action continued throughout the rest of the summer as both sides tried to seize the initiative along their armies' coastal flank. With two dreadnoughts now at his disposal, Eberhard tried to bring the Goeben to action, hoping to trap the faster ship between them. He was unsuccessful, but Breslau had another close encounter, this time with Imperatritsa Mariya and the Black Sea Fleet's new, even more aggressive commander, 41-year-old Aleksandr Kolchak, former commander of the Baltic Fleet's scouting forces.

Kolchak's new strategy was to use Russian superiority in mine warfare to lay a thick layer of minefields around the Bosphorus, hindering the German ships' operations and hopefully choking Turkish coal traffic. Destroyers and submarine minelayers laid new fields within a mile of the strait.

In response, Souchon used reinforcements from Germany to launch a minor U-boat offensive. Four submarines cruised the Black Sea in August and September, 1916, claiming two small steamers but no other successes. Greater targets awaited in the Mediterranean, and most German naval leaders considered submarines operations in the Black Sea a waste.

The Russian side suffered its most serious naval loss in October, 1916. Early one morning sailors walking past Imperatritsa Mariya's forward turret heard an unfamiliar hissing noise. Smoke began to leak out of turret hatches and the canvas blast bags at the foot of the gun barrels began to billow outward. Several sailors raced to set off alarms, but less than two minutes later the forward magazine exploded. Over the next hour 24 smaller explosions followed and the battleship settled to the harbor bottom.

Souchon proved unable to take advantage of the accidental explosion, as the Russians transported troops to Rumania by sea with little interference and then evacuated them with even less trouble. German-Turkish operations moved at a much slower pace as the coal shortages began to take serious effect, being limited to mining and raiding operations by the Breslau and a handful of Turkish destroyers.

The Goeben's crew amused themselves by planting a large garden near their anchorage; before long the two German cruisers in the Black Sea were the only German warships whose crews received a balanced diet.

The SMS Goeben and the Great War on the Black Sea

- Introduction and Opening War Efforts

German Ships Sold to Turkey

First Russian Operation of the War

Black Sea Fleet After Tsar Nicholas II

Map of Black Sea (slow: 85K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 4

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com