Safely into the Dardanelles, Enver Pasha's Turkish government

faced a major problem. The Allied powers were demanding that the two

ships be disarmed and their crews expelled from Turkey.

Safely into the Dardanelles, Enver Pasha's Turkish government

faced a major problem. The Allied powers were demanding that the two

ships be disarmed and their crews expelled from Turkey.

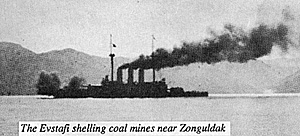

The Evstafi shelling coal mines near Zonguldak

But Enver hit on a clever solution. The two ships would be "sold" to Turkey to replace two new battleships seized days before Turkish crews could sail them from British shipyards.

First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill hoped to augment his fleet strength with the move, but this blunder would cost Britain dearly - one of many he would make before his ouster a year later. Public contributions had helped pay for the warships - nearly every Turkish peasant had sent in his butter-and-egg money in a burst of patriotism. And now all of those Turks felt personally robbed by Churchill.

The German ships hoisted Turkish pennants and their crews donned red fezzes. The ships themselves now bore new names, Goeben becoming Yavuz Sultan Selim (in honor of Sultan Selim the Grim, Turkish conqueror of Mecca) and Breslau becoming Midilli (after a town on the island of Lesbos). German records always referred to them by their German names, however.

The ships entered the Golden Horn, the famed harbor along Constantinople's north shore, to a riotous welcome. Souchon became commander of the Turkish navy, replacing the British admiral Limpus.

More German sailors, disguised as construction workers, filtered down through Rumania and Bulgaria. They had a lot of work to do, repairing and refitting the Turkish fleet. The light cruisers Hamidieh and Medjidieh seemed the most useful units, though small and too slow to operate effectively with the German ships. The old battleships Torgud Reis and Heireddin Barbarossa, launched in 1891 for the German navy and purchased by Turkey in 1910, had given good service against the Greeks but were under repair and considered dangerously slow.

A squadron of German-built destroyers offered some hope, but German officers found them in terrible condition despite their recent delivery. Their crews had never practiced squadron tactics and their captains treated their ships like private merchant steamers, racking up nice profits with their high speed but doing little to prepare for war.

For some time British officers had trained the Turkish Navy, and their guidance did little to improve the force. Souchon and his officers accused the British of systematically working to destroy the Turkish fleet while "assisting" it, and the facts support their charges. Turkey wasted huge sums on "rebuilding" ancient vessels, while new ones like the destroyers fell into disrepair. Lingering effects of this British "assistance" would hamper the Turkish Navy throughout the war.

Through much effort, the Turks and Germans made most of the fleet ready for sea by late October. Souchon and the German government were becoming frustrated. Closing the Dardanelles to all foreign traffic a month earlier had cut the vital supply line between Russia and her western allies, but had not resulted in a declaration of war. An incident to bring Turkey into the war would have to be manufactured.

Raid

On October 27, 1914, the now augmented Turkish fleet steamed into the Black Sea, supposedly for exercises, but carrying sealed orders from Enver to attack the Russian navy.

"Do your utmost," Souchon signalled his fleet. "The future of Turkey is at stake."

Souchon attacked the Russian coast, ruining Enver's carefullyprepared explanation of an encounter at sea with the Russians. Two small Russian warships were sunk and a half-dozen merchant steamers sunk. The Turkish gunboat Berk managed to extort 100,000 gold rubles from the city government and business leaders of Novorossisk in exchange for not bombarding the city and its many oil tanks. After taking the cash, Berk shelled the town anyway.

Militarily, the raid accomplished little. Politically, the results are still felt today. Russia declared war on Turkey, followed by her allies. New fronts opened in the Caucasus and Middle East, as well as the naval struggle on the Black Sea.

Russian Strength

The Russian Black Sea Fleet's strength centered on its squadron of five pre-dreadnought battleships. Unable to leave the sea to join their Baltic Fleet counterparts on the floor of the Sea of Japan in 1905, some dated back well into the last century. Updated somewhat after the Russo-Japanese war, their crews showed remarkably good gunnery skills.

A pair of small, slow armored cruisers made up the scouting force, and a large number of small destroyers were also available. A pair of ancient battleships used as coast-defense vessels took no part in active operations.

An ambitious construction program, spurred by the threat of Turkish purchases abroad, promised to provide a completely new, modern force within the next several years. Four dreadnoughts were in various stages of construction, along with four modern light cruisers and revolutionary new mine-laying submarines.

But the most revolutionary Russian development in naval science would soon come out of the shipyards. In 1913 the destroyer Novik shocked naval designers with its large size and high speed - 1,300 tons and 37 knots. Five similar boats had their commissioning ceremonies interrupted by Souchon's raid on the Black Sea coast, and four more slightly larger versions joined them in 1917. Their size allowing them to operate in much rougher weather than foreign destroyers, these destroyers could slip across the Black Sea at high speed and attack Turkish coastal traffic at little risk to themselves.

While the Russians outgunned the Turks on paper, each side had unique advantages and liabilities. Nothing in the Russian fleet could keep up with the Goeben and Breslau except the large destroyers.

While the pre-dreadnought squadron had greater firepower than the battle cruiser - exactly twice as many heavy guns - the Goeben's speed allowed Souchon to choose the terms for any engagement. The Turkish pre-dreadnoughts were too slow to operate with the Goeben, and also unable to outrun the Russian squadron. Only in the event of severe damage to the Goeben - an event that could knock Turkey out of the war would they enter the Black Sea.

Neither side could afford to ignore sea-borne commerce. Turkey's only coal mines lay at Zonguldak on the coast - and their output could only reach Constantinople by sea. No railroads serviced the frontlines in the Caucasus on the Turkish side, and not enough of them on the Russian side. Both needed to move troops and supplies by ship.

The Russians had learned a few things since their disastrous encounter with the Japanese a decade earlier. A large mine warfare establishment - with specially-built minelayers and most destroyers and cruisers fitted to lay mines - and an industry geared to provide the weapons kept potential sea lanes always dangerous for the Turks and Germans, while the Turkish navy was reduced to fishing Russian mines out of the sea and floating them down the Dardanelles at the British.

The SMS Goeben and the Great War on the Black Sea

- Introduction and Opening War Efforts

German Ships Sold to Turkey

First Russian Operation of the War

Black Sea Fleet After Tsar Nicholas II

Map of Black Sea (slow: 85K)

Back to Table of Contents: CounterAttack # 4

To CounterAttack List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by Pacific Rim Publishing Company.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com