The Muslim commander had selected this spot as the most advantageous terrain for his attack. His plan was to separate the rearward elements of the Crusader army from the main column, and then annihilate Richard's forces in detail. Contemporary sources state the size of Saladin's army at 300,000, but a much smaller number is likely. Indeed, about the only assumption one can rely on is that the Muslim army had a considerable numerical edge over its antagonists. Saladin decided to have his Negro and Bedouin foot-archers strike first with a barrage. followed by an all-out attack.

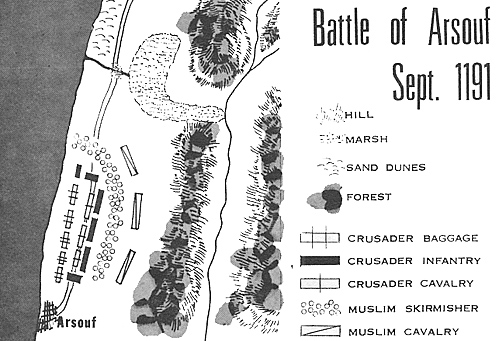

On the morning of the seventh, after Richard had concluded that he would be attacked, he set his march order. On the east flank of the column, and to its front and rear, he placed his infantry, interspersed with crossbowmen and archers.

On the west flank (the seaward flank, unexposed to attack' he placed his baggage train, the sick and the wounded. In the center he place his cavalry column: the Knights of he Temple were in the van, just behind! the forward infantry; the Knights of the Hospital (a similar, elite order of religious knighthood) were in the rear. just forward of the rear-guard infantry. In between the two knightly orders was the rest of the cavalry; English and Norman troops were the King's standard guards.

Richard's plan was to keep marching at all costs, fending off archer attacks with his own bowmen; if Saladin should close for the attack, the march was still to continue, with no one breaking ranks to charge: when Richard had determined that the Muslims had committed themselves, he would order an all- out charge by a pre-arranged signal of trumpet blasts.

Thus, Richard had decided to hold his main punch until the last moment, when there was as little chance as possible for the Turks to make a quick retreat, out of his grasp and back into the woods east of the coast road.

Thus it was that at 9:00 A.M., Sentember 7th, 1191, when the Crusader's column had reached the position along the coast road which Saladin had deemed most advantageous to his own forces, the Battle of Arsouf began.

Battle of Arsouf

The Muslim infantry were the first to stream down from the hills east of the coast road to take to their position and assault. Following Saladin's plan, pressure was particularly applied to the rear of the Crusader column in an effort to divide it from the rest of their comrades.

The bowmen-infantry line at first effectively halted the onslought on the rear, but the Muslims rallied when their cavalry was thrown in, and they broke through to the Hospitallers, who were taking the brunt of the fighting. Messages were sent to Richard, asking permission to charge. No sooner were they received than they were denied; the Hospitallers were now sorely pressed. Although the Muslim darts and arrows were of insufficient velocity to penetrate the European protective armor, it seemed that the air was full of the missiles; and, if they failed to take-a toll of the Latin manpower, their effect was more serious to Richard's cavalry, for mounts were going down left and right. Added to this was the difficulty of keeping in step with the main column while trying to engage in combat with the charging Muslims -- in effect, marching in one direction and fighting in another. The Hospitallers' position was rapidly becoming critical, for they were beginning to fall back into the next cavalry contingent of the Crusader column.

In desperation, the Master of the Hospital rode to Richard and pleaded with him to let them attack. "My good master," answered the King, "it must needs be endured." On riding back, though, and seeing his men on their last leg, he could endure it no longer: in the company of a second knight, he called on St. George, raised his lance, and spurred his horse forward into the midst of the Muslims.

On seeing this, the rest of the knights could not be restrained; squadron by squadron, from the north end of the column to the south, the Crusader cavalry wheeled around to charge. Baha- ed-Din, a contemporary Arab historian who witnessed the charge, spoke of it in these terms:

- I myself saw their Knights

gather together in the middle of

the infantry: they grasped their

lances, shouted their shout of

battle like one man, the infantry

opened out, and through they

rushed in one great charge in all

directions--some on our right

wing, some on our left, and some

on our centre, till all was broken.

The Muslim troops were routed, and streamed back to the hills to the east. Meanwhile, Richard joined the unordered fray, but constrained his knights from chasing Saladin's men into the eastern hills, whereupon the Muslims rallied and counterattacked, only to be pushed back once again.

This sequence occurred three times. Finally, Saladin ordered in his picked Mameluke horsemen in an attempt to take the King's Standard, while he rallied all the troops he could in an attempt to break through to the new Crusader rear. For a moment, it seemed as if the Norman and English Standard guards would give way under the Muslim knights' attack, but a counterattack led by King Richard relieved the guards and pushed the Mamelukes back.

No sooner had this action been completed than the English King saw the imminent danger to his army's rear, and personally led a counterattack on that portion of the line, thereby pushing back Saladin's last attack: the Battle of Arsouf was over.

7,000 Muslims, along with 700 Crusaders, had perished in the battle. It was one of Saladin's worst defeats, but it was hardly decisive, for the Muslim army was far from destroyed. Still, the battle had important effects: first, it increased the confidence of the Christians; and, complementary to that increase, the Muslim morale had fallen. Saladin's army had been ineffectual at Acre, but at Arsouf it had been defeated. Thus, confidence in him was declining: there were instances of insubordination that followed Arsouf, and for Saladin there was only one hope for maintaining his hold on a unified Muslim state: Jerusalem must not fall.

The Crusader Army moved on to take Arsouf, Jaffa, and finally, Ascalon. where it spent the winter. Meanwhile, Saladin had been retreating before him, carrying out a scorched-earth policy.

Thus it was that when Richard again moved out and reached Beit-Nuba with his rested army on January 3rd of 1192, he had unknowingly gotten as close to recapturing Jerusalem as the Christian army would get; for once a council of war was held and the veterans of the Levant predicted disaster for a march any further inland (besides, even if Jerusalem were taken, where would the manpower be to hold it once the non-native Europeans returned to their respective homelands?), King Richard wisely decided to return to Ramleh.

Arsouf Map

A Military History of the Third Crusade

-

Introduction

Jihad

Battle of Arsouf 1191

Conclusion and Bibliography

The Crusader Army

The Muslim Army

Ordnance of Siege Warfare

Crusader Kings

Back to Table of Contents -- Panzerfaust # 65

To Panzerfaust/Campaign List of Issues

To MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1974 by Donald S. Lowry.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com