[As a result of correspondence and my attandance at his lectures, etc. Paddy Griffith has become a friend I meet and correspond with too infrequently. His work and writings on military history are legendary and his knowledge of the subject without peer. We are, therefore, very fortunate to have received the following submission from so distinguished an author. Why the sycophancy, I hear you ask? Well, apart from having a great respect for Paddy's work, I wanted to build up an image before publishing (and being damned for it) the following picture of the author at Namur - in 1957! Sorry Paddy.]

[As a result of correspondence and my attandance at his lectures, etc. Paddy Griffith has become a friend I meet and correspond with too infrequently. His work and writings on military history are legendary and his knowledge of the subject without peer. We are, therefore, very fortunate to have received the following submission from so distinguished an author. Why the sycophancy, I hear you ask? Well, apart from having a great respect for Paddy's work, I wanted to build up an image before publishing (and being damned for it) the following picture of the author at Namur - in 1957! Sorry Paddy.]

In the course of writing a book about The Art of War of Revolutionary France, I naturally found that I had to look not only at the later more `Napoleonic' (and hence perhaps better known) battles of the Revolutionary Wars -- in Italy, the Alps or Egypt -- but also at the very earliest encounters of all. The battles of 1792 were rather different in tone and content from much of what would follow - but they were the essential starting point which shaped the whole era up to Waterloo.

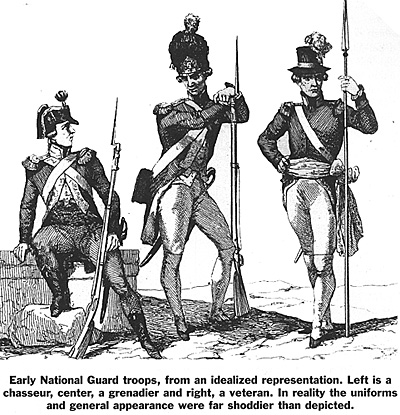

During this `first chapter' of the Revolutionary Wars the most important group of French armies (i.e. the ones ranged along the northern frontier of `la patrie') would fight four distinct campaigns before they finally began to get their act together properly during the summer of 1793. Two of these campaigns turned out to be totally disastrous and chaotic defeats; namely the initial attempt to assail Belgium in the spring of 1792, and the defensive Neerwinden campaign in the spring of 1793. Both of these sequences confirmed the opinion of most military commentators that the improvised French revolutionary militias could not possibly hope to match the mature long-service professional armies of the Old Regime. Obviously a picked and carefullytrained Potsdam grenadier could always 'tower over' a Parisian street-urchin, in every conceivable department and in every sense of the term.

Historical Background

Historical Background

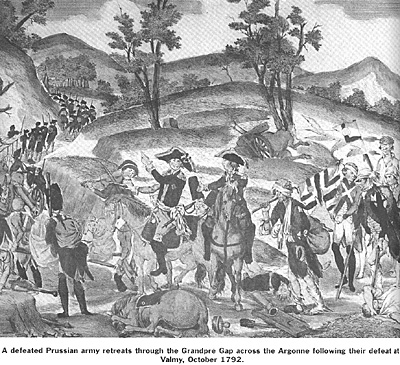

The real shock and surprise to practically everyone, however, was that the other two 1792 campaigns -- those of Valmy and Jemappes -- both turned out to be decisive French victories. Not only was a highly-organised Prussian invasion of France brushed aside almost contemptuously on the field of Valmy on 20th September, but the supposedly formidable Austrian position in Belgium was blown to oblivion on the field of Jemappes on 6th November. Within three short months the French commander in chief, Dumouriez, had triumphantly turned the tables almost completely, and transformed a war on two fronts (Belgium and the Rhineland) into a war on just one front (the Rhineland). All this amounted to a highly spectacular firework display of mobile and 'modern' warfare, which in many ways was perfectly equivalent to anything that Bonaparte himself would later contrive to deliver. It rocked contemporary observers to their very roots, even though the subsequent French defeat at Neerwinden on 16th March 1793 would rapidly give them numerous excuses for reverting to their earlier anti-French and counter-revolutionary prejudices... at least for a few further years.

Besides, the French victories at Valmy and Jemappes had them selves included plenty of factors which could absolve the quality of the defeated armies from serious criticism. The particular excuse that is still most widely favoured today is simply that the French were so numerically superior that they could not possibly have been beaten, no matter how catastrophi- cally inefficient their soldiers might have been. At Valmy they were able to field some 52,000 men against 34,000 Prussians (i.e. odds of 3 to 2), and at Jemappes they had some 45,000 against a mere 13,00( Austrians (i.e. odds of 7 to 2). This shocking ability to concentrate such superior numbers on the battlefield is conventionally seen as a full and sufficient explanation of French victory, requiring no particular skill on the part of the individual soldiers, although in fairness it must be conceded that it did in itself represent quite a major administrative achievement. In this context we should remember the ominous dictum of the Cold War era, with reference to the Warsaw Pact's massive arms inventory, that 'quantity has a quality all its own'.

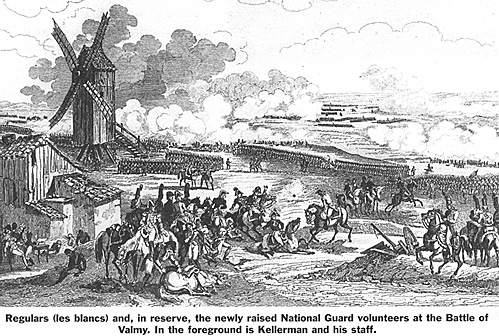

Besides, even despite their great numerical superiority, it was still quite conceivable that the French might indeed have been overcome in either or both of the battles of 1792. At Valmy their solidarity was never really tested at close quarters, and their centre was rather seriously mal-deployed by Kellermann. There seems to be little room for doubt that he had been deeply and personally surprised by the outbreak of the battle at the particular time and place at which it did begin, and he went into it in a haze of disorganisation. Nor could he trust his troops to show the solidity needed to launch a robust offensive, which went a long way to giving this battle its tentative and distinctly 'non-Napoleonic' character.

In many ways, therefore, the Prussians had only themselves to blame for 'snatching defeat from the jaws of victory' on this occasion. Their commanders at first had no idea of the true situation, then showed a disastrous lack of resolution in delaying their decision to launch the crucial central attack - and finally cancelling it after it had advanced merely 200 yards towards the enemy line. They too were being very tentative, even though their battalions doubtless had more cohesion and 'military spirit'. Still later in the day the Prussians were offered a second chance when the French were temporarily numbed by the explosion of two ammunition caissons in their midst - but once again they failed to seize the opportunity. Their king's final decision, after some eight hours of mutual cannonading, that `Hier schlagen nicht' (`We do not fight here') was clearly a major military mistake which threw away a reasonably good opportunity -- in fact the only one that would ever be presented to him -- of winning not just the battle but also the whole campaign, the whole war and Paris.

Equally at Jemappes there are signs that the French might well have lost. They eventually managed to capture the enemy's front line of redoubts only because it was almost entirely unmanned apart from unsupported artillery batteries. This situation represented 'the dark side' of Wellington's famously successful defensive tactic of sheltering his men on the reverse slope of any ridge line. The system would work for him mainly because his infantry and cavalry were normally ready to counter-attack from their sheltered positions at the `psychological moment' after the enemy bombardment had ended but before the friendly artillery on the crest was finally overrun; but at Jemappes the Austrians signally failed to counter-attack in time, thereby surrendering the ground of tactical importance rather lamely to their opponents.

Once they had lost the first line and some of their guns, they found themselves involved in a confused all-arms brawl on a level plateau, in which most of the psychological and numerical factors favoured the French (even despite the `friendly fire' that they were receiving in their backs). The initial Austrian counter- attack was successful enough but, unlike so many of Wellington's, it never seemed to regain sufficient composure or solidity, and was soon swept away by a fresh French onslaught.

Elsewhere on the field of Jemappes the French conceived a grand double-enveloping and encircling manoeuvre, which should surely have been their best method of cashing in on their great numerical superiority.

Unfortunately, however, neither of its prongs won any success at all. De Harville's right flank attempted to make no more energetic an assault than the Prussians had managed at Valmy, and there were great recriminations after the battle. Most of the enemy troops were allowed to walk away unscathed, when by rights they should all have been surrounded and captured. Scarcely less unsatisfactory was the important assault on the village of Jemappes itself, on the French left flank. Depending on who you read, this was either an instant triumph for the flashing revolutionary bayonet, or an embarrassingly limp and long-delayed partial advance, lacking either fervour or cohesion. Once again there were some bitter recriminations, from which the present author regrets that he has ultimately come to accept the latter interpretation rather than the former.

Unfortunately, however, neither of its prongs won any success at all. De Harville's right flank attempted to make no more energetic an assault than the Prussians had managed at Valmy, and there were great recriminations after the battle. Most of the enemy troops were allowed to walk away unscathed, when by rights they should all have been surrounded and captured. Scarcely less unsatisfactory was the important assault on the village of Jemappes itself, on the French left flank. Depending on who you read, this was either an instant triumph for the flashing revolutionary bayonet, or an embarrassingly limp and long-delayed partial advance, lacking either fervour or cohesion. Once again there were some bitter recriminations, from which the present author regrets that he has ultimately come to accept the latter interpretation rather than the former.

French success at Valmy and Jemappes may thus be attributed both to 'own goals' scored by allied soldiers against themselves, and to a narrow victory of French 'administrative' skills, in bringing superior numbers into action, over French military incompetence in many areas of operations and tactics. However, we must also remember that these battles were the first really large-unit encounters of this particular war (and even in this particular generation), and so both sides were presumably equally inexperienced and tentative in the art and science of fighting real battles, as opposed to whatever deep differentials may have existed in their experience of training or exercises.

Neither side could be expected to show the same competence or sureness of touch as they would achieve in later battles, after they had won experience through a costly process of trial and error. The same sort of `learning curve' recurs in many other wars throughout history, and it is often the case that the outcome of a `first battle' between two equally inexperienced military machines will turn on a matter of pure chance, or at least on 'which of the two bunglers happens to make the fewest mistakes'.

In this case it seems fair to assume that the allies, man for man, were on average better soldiers than the French; yet we must be careful to remember that the exact margin of difference is a highly uncertain and controversial quantity. There are two diametrically opposite points of view. On one hand we are faced with a Republican belief that all you need is enthusiasm, the bayonet (and the vote, as a free citizen) in order to beat the effete mercenary slaves of corrupt despotic tyranny; but on the other hand we find a counter-revolutionary belief that it is only years of training and ingrained technical expertise (e.g. in disciplined musketry) that can possibly win battles.

But neither belief seems to be entirely true, and surely neither can stand on its own without quite a few modifications. For example it was their technically very efficient artillery, rather than their bayonets, which seems to have given the French their most telling combat advantage. Conversely it was poor generalship rather than poor fighting qualities which did most to unzip the Austrians and Prussians in both these battles. A large disorganised mob, supported by plenty of Gribeauval's excellent twelve pounder long guns, turned out to be a pretty good match for a relatively few half-battalions of well-drilled professionals who found themselves subordinated to a somewhat uncertain leadership.

Wargaming

For the wargamer, all this poses a very complicated technical question, since the opposing armies were so hugely different in type, structure, composition and numbers, and their areas of strength and weakness were so disparate. In no sense could the two sides be said to be 'equal' or `equivalent', even though it was always entirely possible that the French might have lost either or both of the two battles. We are faced with almost a 'Savage vs. Soldier' type of situation, in which one side has the numbers but the other side has the technology. Yet not even this model is fully appropriate, since the French actually had some of the highest technology of all - in their artillery and in some parts of Dumouriez' higher staffwork (especially since he was working in the friendly medium of a generally supportive civilian population). The Austro-Prussians, for their part, had a very potent Sunday punch in the shape of their core of disciplined soldiers; but they found that they could not use it properly, because their generals often failed to understand what was really going on.

In wargame terms it is fairly easy to invent rules which allocate numerical values to the relative fighting qualities of specific numbers of horse, foot and gun in each army. It is even possible to construct `morale' rules which reflect the temperamental differences between green revolutionary militias and long-service professional grenadiers (or even between long-service French regulars left over from the Old Regime, and lawless provincial Austrian 'free corps'). As a rule of thumb, the suggested military ability of a regular battalion (of either side) should be set at about twice hat of a `volunteer' or `free' one, which should itself be twice that of a battalion of `Federes' (the greenest and most amateur class of revolutionary volunteers).

In wargame terms it is fairly easy to invent rules which allocate numerical values to the relative fighting qualities of specific numbers of horse, foot and gun in each army. It is even possible to construct `morale' rules which reflect the temperamental differences between green revolutionary militias and long-service professional grenadiers (or even between long-service French regulars left over from the Old Regime, and lawless provincial Austrian 'free corps'). As a rule of thumb, the suggested military ability of a regular battalion (of either side) should be set at about twice hat of a `volunteer' or `free' one, which should itself be twice that of a battalion of `Federes' (the greenest and most amateur class of revolutionary volunteers).

The differential of artillery quality should be set at about 5:4 in favour of the French, and in cavalry quality 5:4 in favour of France's enemies. Note that all battalions are assumed to be 600 strong, and all cavalry squadrons 120 strong.

The real problem, however, comes when one tries to legislate for the different backgrounds, skills and perspectives of the command staffs in each case. As Derek Henderson pointed out so appropriately in his `Who do we think we are?' forum in Battlefields, Vol.1 Issue 3, p.44, we cannot, as a player, purport to be the commander of some particular historical army unless we also accept rules which limit us to the sort of options that were historically available to the real commander of that particular army in real life - and blinker us to those that were not.

In the case of Valmy this means that the `Dumouriez' player must be allowed pretty good general strategic intelligence and fairly direct command over his own forces, whereas the 'Kellermann' and `Brunswick' players should have very little of either (The first half of the battle was fought in fog, after all, and only Dumouriez was sufficiently elevated in the command hierarchy to be far enough back from the front lines - safely ensconced in a comfortable chateau - for this to be a technical irrelevance. He was the only true 'army' commander present in this battle, whereas the other two should really be seen only as 'corps' commanders). Initiative to press forward should be severely limited among subordinate commanders and any offensive impetus by either side against massed artillery, in particular, should be accompanied by factored die rolls which might lead their high commanders having immediate second thoughts.

For Jemappes the 'Dumouriez' player should still be given a wide freedom to command whatever combinations seem best, including major encircling offensives; but on this occasion he should not have any direct expectation of immediate or accurate obedience to his orders by any of his subordinates. As soon as the attack is launched, he will be able to influence events not by orders written from the rear but only (and then only 'maybe') if he is physically present with the particular brigade which he wants to influence. On the Austrian side there should be an attempt to hold the entire frontage of the position, even though it is known to be far too long for the number of troops available.

Sources Consulted

A. Alison, History of Europe from the commencement of the French Revolution to the Restoration of the Bourbons (12 Vols., 9th edn., Blackwood, Edinburgh and London 1856); and Alison's Atlas of the Wars in Europe, 1792-1815 (1875 edn., reprinted by Worley Publications, Tyne & Wear 1994)

A M Chuquet - 12 Volume history of Les Guerres de la Revolution, including Vol 2 on Valmy (Leopold Cerf, Paris 1887), and Vol. 4 on Jemappes (1890)

C de la Jonquiere, La Bataille de Jemappes (Chapelot, Paris 1902)

Matti Lauerma, L'Artillerie de Campagne Franqaise Pendant les Guerres de la Revolution (Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki 1956)

John A Lynn, The Bayonets of the Republic, Motivation and Tactics in the Army of Revolutionary France, 1791-94 (University of Illinois Press, 1984)

Valmy and Jemapps 1792

- Historical Background

Wargaming Scenario: Valmy: 20 Sep 1792

Wargaming Scenario: Jemappes: 6 Nov 1792

Back to Battlefields Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com