The Sumerians are our earliest depicted and recorded examples of organised warfare. Having said this the Sumerians are credited with two distinctive military developments. The first is the introduction of bronze into warfare, and the second is the use of the wheel to develop battlewagons or war chariots.

The Sumerians are our earliest depicted and recorded examples of organised warfare. Having said this the Sumerians are credited with two distinctive military developments. The first is the introduction of bronze into warfare, and the second is the use of the wheel to develop battlewagons or war chariots.

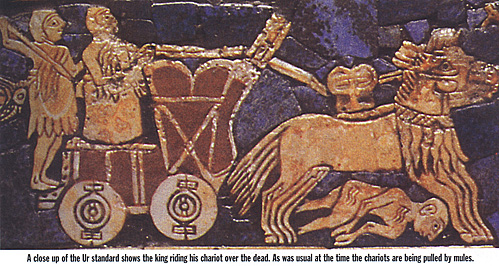

As stated earlier in this article very little on the Sumerian military system is known. What is known comes mainly from the stele of the Vultures as well as the Royal standard of Ur, and from armour and weapons that have been unearthed in grave sites. The royal standard of Ur is a mosaic inlay of shell and lapis lazuli, it shows a scene from a war and has been dated to 3500 B.C.

The first and most obvious piece of military equipment depicted is a Sumerian battlewagon. These battlewagons were low to the ground and had four wheels of solid wood. Each wheel was constructed by clamping three planks together. A hole was pierced in the centre of the wheel and an axle was secured in place on the wheels. This axle would turn in place with the wheels and made for a very rough ride. Tyres on these wheels found in grave sites indicate that they were manufactured from leather. The wheels of these battlewagons were quite large and came up over the bottom of the wagon's platform and would not allow the front axle to swing under the platform, for this reason the turning arc of one of these vehicles was quite large.

The body of the battlewagon was roughly square, made of a woven breastwork that was mounted to the wagon platform. On the rear of the vehicle was a low slung step to facilitate entering and exiting the wagon. For the protection of the crew and driver the front panels of the battlewagon were built higher, in two-round topped shields. Between these shields there was a V-shaped depression which the reins passed through. The reins were ornamentally decorated with beads of silver and lapis lazuli. These passed through a silver ring that was attached to the chariot pole and to this were attached silver headstalls. There were no bits used and the only other element of the harness that has been discovered is a broad collar of metal over leather.

The large battlewagons were pulled by what appear to be four donkeys or onagers. The onager however is reputed to be undomesticatable and the donkey was not yet known in this region. Suffice it to say that four beasts that were mule-like hybrids pulled the battlewagons. In each battlewagon there was a driver and a fighting man; the weapons of the latter are light throwing spears carried in a quiver that was attached to the front of the vehicle. It is believed that there were 4 spears carried, two with pronged ends for use with throwing thongs, and two for use in close quarters combat or melee.

Later in Sumerian history notably in or around the year 2,700 B.C. the clunky four wheeled battlewagon gave way to a lighter and smaller two-wheeled car. It is believed that these cars were simply used as a royal shuttle service for the CIC and his subordinates as well as a messenger service.

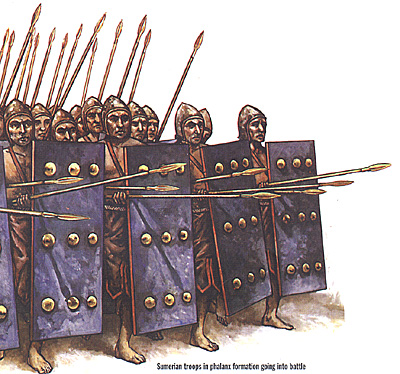

The Sumerian infantry went into battle wearing large conical helmets with fixed cheek pieces and chinstraps. The straps were most often made of leather but examples of silver chains have also been found. The helmet is the only actual metal armour that Sumerian soldiers wore. The common soldier is depicted as wearing over his body, kilts cut in points and having leather strips that were sewn to a belt. Some indications that the kilts were actually made from wool or long tassels of goat hair have also been made.

The Sumerian infantry went into battle wearing large conical helmets with fixed cheek pieces and chinstraps. The straps were most often made of leather but examples of silver chains have also been found. The helmet is the only actual metal armour that Sumerian soldiers wore. The common soldier is depicted as wearing over his body, kilts cut in points and having leather strips that were sewn to a belt. Some indications that the kilts were actually made from wool or long tassels of goat hair have also been made.

Over the kilts were worn long and heavy cloaks that were made of leather or felt. Spots or decorations depicted on these cloaks indicate either spots from a leopards skin, or metal roundels or other embosses that were used for added protection. These cloaks provided a fair amount of protection for the soldier. The cloak was fastened at the neck by a toggle and hung open down the front. If the warrior was part of a skirmisher line or light infantry then the heavy cloak was often replaced, and a shorter cloak or shawl was worn that went around the waist and then over the left shoulder.

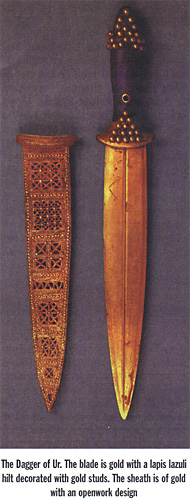

The Sumerian warrior carried a short thrusting spear, a battle-axe, and a dagger or scimitar into battle. Examples of pear shaped stone maces have been found but, by the time of the major wars, this weapon was largely abandoned and only used as a symbol of rank. Another weapon, which may be regarded as a survivor from an earlier period, is the scimitar. The scimitar blade was manufactured of thin copper sheets and then attached to a crooked wooden handle. The blade was secured to the handle by copper bolts and a band of gold. Examples of arrowheads as well as decorated bows have also been found in Sumerian graves despite the fact that archers were not employed for use in the military It is believed that archery was only used for hunting purposes and lacked the necessary prestigious overtones for military use.

The main body of the Sumerian army was made up of heavy infantry units that were organised into phalanxes. In fact it is widely believed that the Sumerians were the inventors of the infantry phalanx. Sumerian artists have illustrated the phalanx as being 6 files or columns wide, and 10 ranks or rows deep. By executing a simple left or right hand turn the march-column became a battleline 10 files wide and 6 ranks deep. The use of a phalanx requires a great deal of training and discipline, and the fact that standards were carried implies that regiments and units organised on a territorial or clan basis were used.

The main body of the Sumerian army was made up of heavy infantry units that were organised into phalanxes. In fact it is widely believed that the Sumerians were the inventors of the infantry phalanx. Sumerian artists have illustrated the phalanx as being 6 files or columns wide, and 10 ranks or rows deep. By executing a simple left or right hand turn the march-column became a battleline 10 files wide and 6 ranks deep. The use of a phalanx requires a great deal of training and discipline, and the fact that standards were carried implies that regiments and units organised on a territorial or clan basis were used.

These units were well equipped and organised and the armies of the various city-states were capable of giving a good account of themselves. The wars fought by these armies were not bloodless skirmishes they were serious affairs. Figures in inscriptions indicate casualties suffered at the hands of these armies ranged from 3,600-12,000 killed and 5,0007,000 taken prisoner per battle. An account of an invasion of Elamites in the year 2750 B.C. by a force of 600 men on the city of Lagash states that only 60 of them escaped death at the hands of the Sumerians. Although this should not be regarded as a serious invasion attempt, the fact that only 60 survived should give us some indication that the armies of the city-states were quite large, well equipped, and capable of taking the field at short notice.

The front rank of troops in the phalanx carried large rectangular shields covered in hides and decorated with metal studs or other designs. For wargame purposes you may elect to have all of your troops protected by shields. It is simply impossible to determine if the depiction of soldiers in the front ranks as being the only soldiers that carried shields is fact, or simply an artist's rendering. It is widely believed that shields were often not used, because it restricted the soldier to one less weapon.

Sumerian victories in battle were usually celebrated by a wholesale slaughter of prisoners. Those that were spared were taken off and enslaved or held for ransom. If a town was taken it meant its pillage and destruction. When the Sumerian Rim-Sin took the town of Isin the entire population that had survived scattered and left the city desolate. The ruthless character of the wars between the city-states is one of the reasons that led to the eventual decay of Sumerian power and the disappearance of its culture.

Sumerian victories in battle were usually celebrated by a wholesale slaughter of prisoners. Those that were spared were taken off and enslaved or held for ransom. If a town was taken it meant its pillage and destruction. When the Sumerian Rim-Sin took the town of Isin the entire population that had survived scattered and left the city desolate. The ruthless character of the wars between the city-states is one of the reasons that led to the eventual decay of Sumerian power and the disappearance of its culture.

The organisation of the army is pretty standard. An overall CIC and several sub-commanders command the army as a whole. The CIC is always the ruling monarch of a city-state or the kingdom as a whole after unification. Each unit is further commanded by separate unit command stands that must be represented for proper command function of the unit. A typical unit command stand will have an officer, a standard bearer, and a musician.

All commanders are to be represented on the tabletop battlefield in battlewagons. Messengers are necessary to relay orders or changes of orders to other sub-commanders or units. Keep in mind the extreme slowness of the battlewagons when commanding your Sumerian armies. Messengers will need to be foot messengers, as the horse was not known in Sumeria at this time.

Akkadian armies were also formed into units and the command structure was similar to that used by the Sumerians. The phalanx was not used by the Akkadians however, primarily because they were from mountainous country, and did not facilitate this type of formation. Weapons used by the Akkadians are the javelin, the battle-axe, and the bow.

There was no regular standing army in Sumeria. Every citizen was a potential soldier and all were liable to be conscripted. The king always led his people personally into battle, fighting in the fore. A permanent organisation existed for this citizen army and there were officials that were responsible for calling out the levies. In the third dynasty of Ur and earlier under the Hamurabi code, a system of the military is reflected that was used to safeguard the throne or to be used for sudden emergency expeditions.

This army is separate and distinct from the levee en masse of the standard army. The regulars were recruited from the higher ranks of private society. These regulars were paid in the form of land grants. This land was to be cultivated by the recipients; failure to do so meant forfeiture of the land. This land if properly cared for by the recipient was inalienable and could be passed down to the son. However when this occurred the same military duties that were bestowed on the father were now the responsibility of the son. One third of the profits obtained from the land went directly to the landholder's wife or son of the holder, who cared for the land whilst the father was on campaign. The soldier "ate at the King's cost" when mustered under the colours. If he was captured the ransom was paid from his private fortune. If a poor soldier was captured, the temple where he worshipped paid the ransom and, failing the temple, then the State would pay.

The soldier also enjoyed protection from the civil authorities; this was a very necessary protection for a man that was away from home for long periods of time. In return for these rights and protections he was absolutely at the king's disposal. A man could not get out of performing his military duties, and the procuring of a substitute to serve for him was against the law, and considered a capital offence. The levee en masse was filled by the middle-class of society. The burgher classes were not professional soldiers and performed mainly camp duties and possibly a light infantry arm of the military service. Slaves of course were exempt from military duty as an armed slave was considered a dangerous slave.

The Sumerians

- Historical Background

Civil Wars and the King Lists

Military Organization and Equipment

Wargaming Terrain and Scenarios

Back to Battlefields Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com