THE CIVIL WARS

Exactly when the land of Sumer became unified is largely speculation. The main reason for this is due to the fact that most of the information covering this period comes from what is known as "The King Lists". The list was put together at the end of the 3rd dynasty of Ur around 2000 B.C. by Sumerian scribes. The information given in the list covers names of rulers as well as lengths of reigns. The sources for this information came from references to events in omens, specific legends, royal inscriptions, as well as the year names of kings. The list was put together in an attempt to list the past glories of the great days of the past for posterity.

The list gives the names of kings arranged in their dynasties, the number of the years of the reign of each, and a total number of years for the dynasty.

The main problem with the King Lists is the fantastic length of reign for each of the rulers. This makes the lists' value, at least as far as an historical document, uncertain at best. The 10 ancient kings that ruled prior to the "flood" are credited with ruling for a period of 241,200 years when added together. These figures are recorded in multiples known as sars, which are cycles of 360 years each. These fantastic sums are further confused by different systems of notation, but even so it is not difficult to see that these dates or periods of rule have been modified to conform to some system of astronomy. Even after the "flood", though the reigns are not recorded in the same manner (reigns are not determined by sars), the lengths of the reigns is no less exaggerated. For example, of the kings of Kish, one is credited with a rule of 1,500 years, and three with 1,200 years each, and the 23 kings between them account for 24,510 years and 3 months.

Another point of confusion or criticism that is directed at the list is the fact that names of certain kings reappear later as gods, heroes, or mythological legends. An example of this is the famous Gilgamesh of Erech who is the hero of the great epic legend of the Flood. In fact it is not until the last 7 names of the dynasty of Erech that the kings lose their divinity and the years of their reigns become more in line with reality and span normal mortal life. A sample of the first part of The King Lists is given below:

THE KING LISTS

"The Flood came. After the Flood came, kingship was sent down from on high"

"After kingship had descended from heaven, Eridu became the seat of kingship. In Eridu Alulim reigned 28,800 years as king; Alagar reigned 36,000 years- two kings reigned 64,800 years. Eridu was abandoned and its kingship was carried off to Badtabira."

Are the king lists to be disregarded then as mere fantasy? Until recently none of the names in the list up to the third dynasty of Kish (the 8th in order after the flood) were substantiated. However the discovery of monuments of the 1st dynasty of Ur (the 3rd after the flood) helps to confirm the historical character of the lists, and points to a definite underlying truth that is present in spite of the fantastic dates and divine names given in the lists.

| KINGS THAT REIGNED BEFORE THE FLOOD | ||

|---|---|---|

| NAME | CITY | LENGTH OF REIGN |

| A-lu-lim | Eridu | 8 sars = 28,800 years |

| A-la-gar | Eridu | 10 sars = 36,000 years |

| En-me-en-lu-an-na | Badtabira | 12 sars = 43,200 years |

| En-me-en-gal-an-na | Badtabira | 8 sars = 28,800 years |

| Dumuzi "the shepherd" | Badtabira | 10 sars = 36,000 years |

| En-Sib-zi-an-na | Larak | 8 sars = 28,800 years |

| En-me-en-dur-an-na | Sippar | 5 sars, 5 ners = 21,000 years |

| Du-du (?) | Suruppak | 5 sars, 1 ner = 18,600 years |

Another cause of confusion is the fact that the king lists were supposed to include only those overlords, which became rulers of the country as a whole. It is therefore difficult to understand why contemporary dynasties appear in them at all, if in fact some are inserted who can at most have been rival disputants for the hegemony, and why such a monarch as Eannatum of Lagash whose dominion extended over all of Sumer was omitted from the lists. It has been suggested that the compilers of the list had some other motive for what they did.

Perhaps they only had at their disposal a very limited or incomplete set of material for history. Local records may also have given prejudiced or partisan views of events within a narrow scope as they affected certain cities. In any case one would be ill-advised to take the king lists at their face value. The information contained within must be taken with a grain of historical salt and when ever possible backed up with information from other verifiable sources.

The period of the civil wars was no doubt a time of turmoil and competition for dominance. One city-state after another was constantly competing for supremacy but they were either too weak to succeed or not quite strong enough to hold onto what they had conquered for long. It should not be taken for granted that the civil wars were completely fought by the Sumerians alone. There is much evidence to the contrary that would suggest that outside influences had major roles during the civil war period in Sumerian history.

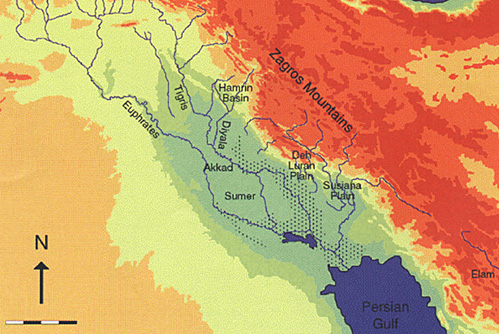

For example a statement suggests that the dynasty that was founded by Mesannipadda placed its capitol or governmental seat in the city of Awan. This city was situated to the east of the Tigris river and it has been argued rather well that the Elamites were now taking part in the wars and may have even been responsible for the downfall of Ur.

One thing is quite clear the Semitic north was reasserting itself against the South (Sumer). On three separate occasions the overlord-ship of Sumer was awarded to Kish, once at Opis, once at Mari, and once at Hit on the Euphrates. The rulers of Mari did write in Sumerian but it is not clear what their racial stock was. The first three kings of the dynasty of Opis had Sumerian names but the rest are Semitic. All of the names of the kings from the fourth dynasty of Kish are also Semitic, and when Lugal-zaggizi of Erech rebelled against Kish, he conquered and subdued all of the land from the Upper to the Lower Sea. This overlord of a would-be Sumerian empire proclaimed his victories in the Semitic tongue. The activities of the northerners resulted in the division of the land into two parts, the Semitic-speaking north (Akkad), and the Sumerian south. Even so this did not change all-tooterribly the land's civilisation. The Akkadians had learned all that the Sumerians had to teach them. They were now on an equal footing with their masters and in the process of learning they had not lost the advantage of being a sterner and more warlike people.

One thing is quite clear the Semitic north was reasserting itself against the South (Sumer). On three separate occasions the overlord-ship of Sumer was awarded to Kish, once at Opis, once at Mari, and once at Hit on the Euphrates. The rulers of Mari did write in Sumerian but it is not clear what their racial stock was. The first three kings of the dynasty of Opis had Sumerian names but the rest are Semitic. All of the names of the kings from the fourth dynasty of Kish are also Semitic, and when Lugal-zaggizi of Erech rebelled against Kish, he conquered and subdued all of the land from the Upper to the Lower Sea. This overlord of a would-be Sumerian empire proclaimed his victories in the Semitic tongue. The activities of the northerners resulted in the division of the land into two parts, the Semitic-speaking north (Akkad), and the Sumerian south. Even so this did not change all-tooterribly the land's civilisation. The Akkadians had learned all that the Sumerians had to teach them. They were now on an equal footing with their masters and in the process of learning they had not lost the advantage of being a sterner and more warlike people.

The French mission at Tello has unearthed some more prominent information that has helped to shed some new light on the civil wars period. The mounds at Tello lie on the course of the ancient Tigris river that was canalised by Entemena, an ancient city of Lagash, which never attained to the rule of the land as a whole. It should be noted, however, at this time that a house that used the title of king (lugal) rather than governor (patesi) ruled the city. The first of these was Ur-Nina (2900 B.C.) who enjoyed a peaceful reign, for records found at the site indicate

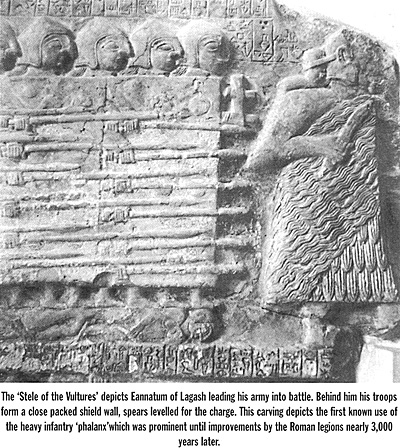

He dealt with matters mostly of the building of temples and the digging of canals, as well as the fortification of his capital. His grandson Eannatum was on the contrary a man of war. Between Lagash and the city of Umma, which lay to the north, there existed an ancient quarrel that had broken out into open hostilities.

Umma was supported by Kish and felt confident and once again declared war on Lagash. The patesi of Umma was slain and terms were imposed on Umma and the boundaries between the two states were fixed to the distinct advantage of Lagash, and tribute was set. The victory of Eannatum is recorded on the famous stele of the Vultures, which may be seen in the Louvre in Paris. Not content with defeating his enemies Eannatum embarked on a war of conquest. He claims to have conquered Ur, Erech, and Kish, while the king of Opis beaten within the walls of his own city. Even Mari on the Euphrates as well as the land of Elam is said to have been conquered. If these boasts are even remotely true then the king of Lagash was de facto ruler of all of Sumer and Akkad. This point is further driven home by the fact that he had made benefactions to the holy city of Nippur.

However this triumph was short-lived for within a generation the city of Umma seized the canal which was the main source of contention between the two towns and had destroyed the stele of the Vultures by fire. Later they had even defeated and killed Eannatum. Entemena his nephew restored the position, defeating Umma and then installing his own governor. New canals were dug so that the enemy could not as easily interfere with the water supply for the city of Lagash. A grateful people later deified him and for nearly 1000 year's statues were still erected to his memory.

The next ruler was Enannatum II he was the last of his line and was succeeded by a high priest of Ningirsu (the patron god of the city). Documents show that the next two reigns of Lagash enjoyed a time of considerable peace, seeing that even the people of Umma (the former enemy) had complete religious and civil liberty. This peace was probably enforced, for the kings of Kish seem to have recovered their rule over the south and even to have interfered with the appointment of local governors. It is typical of the period that material prosperity coupled with the fact that the seats of government were at a great distance from the local authorities, permitted wholesale corruption and oppression to exist. It took the rule of a strong man named Urukagina who threw off his allegiance to Kish and declared himself king of Lagash to bring about the changes necessary to bring this corrupt system to an end.

Like many others before him he had found it necessary to issue a series of enactments to stop the abuses of the lower classes. Most of these reforms seem to have been directed against extortion by the priesthood. There are no inscriptions or stele that depict warlike exploits of Urukagina. Instead he found an outlet for his energy in temple building, and during his relatively short reign he had rebuilt all of the temples of Lagash. The many priests that suffered from his social reforms could not accuse him of a lack of piety. In the sixth year of his reign the end suddenly came. The army of the city-state of Umma had made a sudden and unprovoked attack against Lagash and seized the city, killed the king, burnt the temples he had rebuilt, and carried off the image of his god Ningirsu. This act is well documented in a lament that was written by a priest or scribe from the defeated city and was found in the ruins by the French mission.

The patesi of Umma, Lugal-zaggisi followed up his destruction of Lagash by a reign of conquest that made him master of the entire delta. The southern cities seem to have surrendered to him without any great struggle for he had adopted their gods as his own. He had bestowed on the temples of the south his royal seal and then moved his capital to Erech and ruled his domain from there. It is surprising that no mention of a state of war between Umma and Kish is made. More so because Kish lay across the direct line of advance up river and should have been expected to resist the advance. Also Lugal-zaggisi had once been a vassal of the king of Kish and was now in seemingly open rebellion against his suzerain. The main reason for this lack of open conflict or war would seem to arise from the fact that he (Lugal-zaggisi) was able to take advantage of internal conflict within the capital. Sargon a cup-bearer of Kish revolted and set up a rival capital in the new city of Agade; since Lugal-zaggisi had friendly relations with Sargon he fostered the revolt and welcomed the split which helped to weaken the Semitic state.

The patesi of Umma, Lugal-zaggisi followed up his destruction of Lagash by a reign of conquest that made him master of the entire delta. The southern cities seem to have surrendered to him without any great struggle for he had adopted their gods as his own. He had bestowed on the temples of the south his royal seal and then moved his capital to Erech and ruled his domain from there. It is surprising that no mention of a state of war between Umma and Kish is made. More so because Kish lay across the direct line of advance up river and should have been expected to resist the advance. Also Lugal-zaggisi had once been a vassal of the king of Kish and was now in seemingly open rebellion against his suzerain. The main reason for this lack of open conflict or war would seem to arise from the fact that he (Lugal-zaggisi) was able to take advantage of internal conflict within the capital. Sargon a cup-bearer of Kish revolted and set up a rival capital in the new city of Agade; since Lugal-zaggisi had friendly relations with Sargon he fostered the revolt and welcomed the split which helped to weaken the Semitic state.

For the Semitization of the north which helped to make it a distinct country, and the domination of the upstart Akkadian power over the south gave birth to a new spirit of Sumerian nationalism. Lugal-zaggisi posed as the champion of Sumer. There is no other explanation possible for the fact that he so easily brought the southern cities into his fold. In fact they had been brought so securely into the fold that when the eventual duel came with Agade, he was followed into battle by no less than 50 governors of Sumerian states. His shifting of the capital to Erech itself was a bid for nationalist support. Umma itself had no traditions of empire and to elevate it would be to perpetuate old local rivalries. Erech had been the seat of the oldest southern dynasty and the title of "Lord of the Province of Erech, king of the Province of Ur" was a symbol of Sumerian unity.

Lugal-zaggisi's campaign to the northwest was no more than a raid and achieved no lasting results. In a period of 3 or 4 years the land which he overran owed an allegiance not to him but to Sargon.

The new king of Akkad ascended the throne by rebellion against his master and began the rule of a kingdom that had been reduced to the level of a mere city-state. He would eventually make it the capital of one of the greatest empires that Mesopotamia had yet known. Sargon realised that the danger point for Akkad lay to the north. Sumer and Akkad had formed one kingdom in the past and might do so again in spite of the racial differences and he fully intended to absorb the southern country into his own, but he could wait and bide his time for that. Sargon then gave the south a respite and turned his attention in the opposite direction.

The new king of Akkad ascended the throne by rebellion against his master and began the rule of a kingdom that had been reduced to the level of a mere city-state. He would eventually make it the capital of one of the greatest empires that Mesopotamia had yet known. Sargon realised that the danger point for Akkad lay to the north. Sumer and Akkad had formed one kingdom in the past and might do so again in spite of the racial differences and he fully intended to absorb the southern country into his own, but he could wait and bide his time for that. Sargon then gave the south a respite and turned his attention in the opposite direction.

He first secured his hold on the upper Euphrates and advanced north to where the city of Baghdad now lies and attacked Assyria. From Assyria he marched east and conquered Kirkuk and Arbil and then he conquered the Guti hill-men from the Zagros mountain range. From the area of Baghdad he marched south to Malgium, the area between the Tigris and the Persian Hills near Amara, and then carried a raid into Sumer and captured Lagash. Sargon by this time had thoroughly consolidated his position and was ready to negotiate with Lugal-zaggisi. He then invaded Sumer full-scale, defeating its national army, and carried off the king to Nippur. Ur held out but was captured and it walls razed to the ground. The capture of Umma put out the last of the embers of the fire of resistance, and the soldiers of Akkad had made it to the waters of the Persian Gulf.

But Sargon had no desire to deal harshly with the Sumerians of the south. There was a custom that had last been honoured by Nabonidus of Babylonia in the 6th century B.C. The custom stated that the eldest daughter of the reigning monarch become the high priestess of Nannar the patron deity of Ur. A relief in alabaster has been unearthed and it depicts Sargon's daughter holding this sacred office. This gesture was obviously done to conciliate the religious feelings within Sumer. The Akkadians assimilated the entire civilisation of their Sumerian neighbours into their own society, religion, cosmology, legends, pantheon, everything.

After consolidating his power in the delta, Sargon then turned towards foreign wars. In the east Elam submitted, in the west the Mediterranean, and overran Syria as far south as the Lebanon. The sole purpose of these foreign wars was to control the major trade routes as well as the sources of that trade. Even though the Akkadians attempted to appease the Sumerians by adopting their rites and customs, this still proved little comfort to the conquered Sumerians. Sargon's rule came to an end under a general revolt by the Sumerian provinces under the leadership of the city-state of Ur. The rebellion was crushed and many captives were taken and enslaved.

These revolts would continue to pop up and spread with every new Akkadian ruler that ascended to the throne. However the policy when dealing with the Sumerians was still one of conciliation. In fact this conciliation was so strong that even some Akkadian towns (Sippar) rebelled on the side of the Sumerians during one of the general revolts that constantly occurred. Naram Sin was on the throne during one of these revolts, and not only put the revolt down but expanded the empire to the limits that only Sargon had previously achieved. Naram Sin's famous stele shows his victory of a people far to the east of the Tigris river practising the Sumerian religion and customs.

So even in defeat we see quite clearly that the Sumerians were still not really defeated. Their culture not only continued to thrive but also as we can see it even was spread into other lands through the use of Akkadian arms. Also under Akkadian rule we begin to see an influx of names that are clearly Sumerian as holding high governmental offices, as well as the Governorships of the south country.

After Naram Sin stepped down, the king Shargalisharri succeeded him; during his reign, the empire that was begun by Sargon and taken to its greatest extant under Naram Sin, was invaded by barbarians from the north. These forces were the Guti and they overran the land and the country crumbled. A frail line of nobles was able to hold on to local rule at Agade and even at Erech but this did not last for long. The barbarians who knew nothing of kingship spread a total veil of anarchy across the whole land. No records or inscriptions of any kind exist from this period in Sumerian history and the period is regrettably left blank.

After Naram Sin stepped down, the king Shargalisharri succeeded him; during his reign, the empire that was begun by Sargon and taken to its greatest extant under Naram Sin, was invaded by barbarians from the north. These forces were the Guti and they overran the land and the country crumbled. A frail line of nobles was able to hold on to local rule at Agade and even at Erech but this did not last for long. The barbarians who knew nothing of kingship spread a total veil of anarchy across the whole land. No records or inscriptions of any kind exist from this period in Sumerian history and the period is regrettably left blank.

The Guti did learn to form an organised government over time, and also installed kings to rule over their newly formed empire. It is to the Sumerians credit that their culture and civilisation survived the Guti invasion. Like the Akkadians it was not long before the Guti were worshipping the Sumerian gods and adopting Sumerian culture and customs. The Guti were not capable of the vast administrative knowledge required to run a kingdom of this size, and we begin to see Sumerians given the posts of patesi (governors) and other posts of high office. So like the Akkadians the Guti became so thoroughly Sumerian it was as if the Sumerians had never been invaded, and once again they were conquered without being conquered.

The rule of the Guti lasted for 125 years during this time a Sumerian renaissance occurred and once again open revolt ensued. A Sumerian patesi from the city of Erech who was named Utu-khegal revolted against the "enemy of the gods" and declared Sumerian independence. The Guti attempted to make peace through negotiations but they failed, and war broke out. During the large battle that followed the failed peace talks Tirigan, a Guti ambassador, was abandoned by his own soldiers and taken captive by the people of the city of Dubrum. With this final blow the Guti were expelled from the land and Utu-khegal ascended the throne as king and new Sumerian dynasty was born.

The Sumerians

- Historical Background

Civil Wars and the King Lists

Military Organization and Equipment

Wargaming Terrain and Scenarios

Back to Battlefields Issue 10 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com