Was Nieuwpoort Special?

By the time of publishing I guess the year 2000 will be history already.This remarkable year, full with celebrations of all kinds, also happened to be the year of the 400th anniversary of the daring expedition into Flanders by the Dutch States' army and the ensuing battle at Nieuwpoort on 2nd July 1600. Besides Arnheim (Operation Market Garden in 1944) Nieuwpoort is perhaps the best remembered (military) event in Dutch history, at least by Dutch natives.

During the entire 80 Years War (1568-1648) this battle was one of the rare Dutch/Orangist victories achieved over a Spanish army in a larger scale face to face battle.Although it was less a regular battle, since it resembled more a series of dashes in the dunes, with troops fighting from one dune-top to another. The importance lay however not so much in the battle or victory itself, since a) the victory was achieved a bit lucky and b) the exploits of this victory were at longer terms almost neglectable.

For military historians the importance of the battle lays more in the insight it gives in the deployment and tactics used by Maurits van Nassau, after years of development together with his nephew Willem Lodewijk van Nassau.Tactics, although based on antiquity, which were regarded as a new and revolutionay concept, that was to be followed by many great comman-ders throughout Western Europe during the decades to come.

First I'll try to provide you with the inevitable historical and military background leading to this famous battle. I've done my best to keep it short.

Political Background

Since 1568 the Netherlands, actually a conglomerate of 17 Provinces, were involved in a long lasting struggle with Spain, called the 80 Years War A war with both independence and freedom of religion as main issues. Albertus von Habsburg, a nephew of the Spanish King Philip II, was Governor and Archduke of the Netherlands as well as captain-general of all troops under Spanish command in the Netherlands.The Spaniards then controlled about all the Provinces south of the great rivers Maas, Rijn and Waal. The 7 Northern Provinces of the Netherlands had seperated themselves from the rest in 1581. Leading person here, although employed and controlled by the federally organized States General, was Prins Maurits van Nassau, son of Willem van Oranje (the Silent, who had been assasinated in 1584). Maurits was also captaingeneral of all troops in Dutch pay, since 1579 referred to as 'Het Staatsche Leger', or the States' army in English.

During the 1590's Maurits had managed to bring all Northern provinces under Orangist control and thus securing the north-eastern frontier. During some important sieges he had been able to exploit his new theories on siegewarfare, which he had developed together with his nephew Willem Lodewijk. Up to now they had'not had any opportunity to test their 'new' tactical concepts on a real-life adversary.These tactics used small flexible tactical units in the field, which were able to exploit their total firepower to a higher degree. In the cavalryarm the lance had been abolished and the reiter had developed into real cuirassiers, mainly charging with the sword.

Strategic Situation

By the end of the century increasing financial problems led to more serious and extensive mutinies amongst the Spanish troops. The States General thought the time right now to deal a severe blow to the Spaniards. Their object was the coastal region of Flanders. Why there? Well, Oostende was already under Orangist control since 1576. However Duinkerken and to a lesser degree Nieuwpoort formed a plague, harbouring a small Spanish naval squadron and a large number of privateers, tacitly permitted by the Spanish authorities. They caused much damage to the Dutch trade and fishery. Moreover these harbours were arrival points of most Spanish reinforcements and supplies.

Prins Maurits wasn't so happy with these plans. He could only field 14.000 troops, including garrison-troops of several important frontier towns. He thought this army too weak to face veteran Spanish troops in a regular confrontation when invading Flanders. He feared the Archduke might still be able to rally his mutining troops and confront him with superior numbers.Velasco, who commanded an army near Nijmegen, would be able to field about 7.000 foot and 1.000 horse, to which might be added about 5.000 garrison troops in Flanders as well as an unknown number of mutineers, which might eventually rally to the Spanish standard. In case of a defeat the Netherlands would be left without sufficient protection. Moreover Maurits realised that the mere possession of the coastal towns in Flanders without some back-cover wouldn't work.

Nevertheless on 20th may 1600 the States of Holland, strongly influenced by the mighty secretary Johan van Oldenbarneveld, decided to attack Duinkerken. Although Maurits didn't agree with the intentions of the States-General, he decided to lead his troops during the campaign personally, one of his reasons being to watch over his precious trained troops.

Let's Make Up for Flanders

With all the plans and alternatives that were made, most important factor was how much time it would take before Velasco would be informed about the Orangist intentions and how long it would take his troops to march the 300 km from about Nijmegen over Maastricht to Duinker-ken. Estimated was that at a speed of I 5km a day, this would take about 20 days.

Most troops gathering at Dordrecht, all contingents finally met at fortress Rammekens nearVlissingen on June 20th.The impact of this enterprise was enormous for these days, requiring: a transport-fleet of 112 boats for Oostende and a landing-fleet of 1.138 boats for Nieuwpoort. About I boat/ship was needed for 10 horses + men and 6 ships for one company of foot. In addition there seem to have been about 190 sutler boats accompanying the fleet and a convoy of 16 warships. On board were 13.000 foot soldiers, 2.700 riders with their horses and about 2.300 other personeLAlso a train of boat-bridges, 37 artillery-pieces and 100 wagons with another 250 horses had been shipped. Surely an enterprise not being unnoticed by the Spanish spies. Some diversions along the east-frontier mist their goaLVelasco was alarmed timely and started to march south.

Since the wind blew from the wrong direction, this prevented a landing at Oostende. The original plan to disembark at Oostende and march from their to Duinkerken, by way of Nieuwpoort, had to be abandoned.After some debating and a decision being urgent, since the horses had to get on land soon, plans were altered, with Duinkerken staying the prime target. On the morning of June 21st it was decided that the main fleet would land at Philippine that same day. I 2 Warships together with 150 supply ships would sail to Oostende. This meant that many more wagons and draught-horses were needed, since the original plan had reckoned with provisioning of the troops over sea. Moreover 5 more days would be needed to reach Nieuwpoort,giving Velasco also 5 more days to reach the coast.

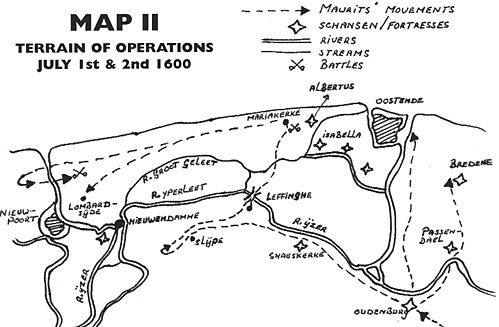

MAP 1 shows the entire route the army followed from the fortress Rammekens to Nieuwpoort.

The Road to Nieuwpoort

I'll skip all the details of the march to Nieuwpoort (see my articles in Arquebusier Vol. XXIV). On June 21 st at 5PM the advance guard landed at Philippine and cleared the coast from Spanish troops which manned some small redoubts.

At Philippine the following troops were mustered by Prins Maurits:

- Infantry 13,150/128

Cavalry 2,000/25 comp

Attached cavalry personel 700

Train 1,050/10 comp

Staff 100

17,000

Total horses

Fighting horses 2,000

Pack horses 700

Draught horses 250

Staff 100

3,050

The unshipped train consisted of 6 half-cannon, 4 field-pieces and 100 wagons. The remainder of the artillery was destinied for Oostende.

From Philippine the army started it's troublesome march into the direction of Nieuwpoort.

The entire column measured about 16 km and it's speed was dictated by the slowest element, the artillery and train. The latter moved slow by lack of horses, about 4 km/hour. So the entire column took 4 hours to pass by. The army marched over Assenede and Eeklo to Brugge.

June 28th Oudenburg was reached, where the large redoubt ('schans' in Dutch) was found deserted by the Spaniards. The schans at Oudenburg and some smaller ones at Snaeskerke, Bredene and Plassendael were garrisoned. The Count of Solms was sent to Oostende with the advance-guard to capture the strong schans Albertus, West of the town. June 29th the schans surrendered after a short bombardment. Next Solms marched across the beach to Nieuwpoort.

Meanwhile along the road from Oudenburg to Leffinghe carpenters and pioneers were busy repairing roads and bridges, this being the shortest way to reach the schans at Nieuwendam-me, near Nieuwpoort. Friday 30th Maurits left Oudenburg with the centre of the army and tried to reach Nieuwendamme. However his boat-bridges being to short he was unable to cross the streams Groot Geleet and IJzer and had to return.The plan to besiege Nieuwpoort both over land and sea, had to be abandoned.

The situation at daybreak of July I st was as following: Prins Maurits at Mariakerke with the bataille, his nephew Count Ernst van Nassau at Leffinghe with the rearguard and Count Solms at Nieuwpoort with the adavance-guard. Probably being so occupied by their own troop movements and probably over-confident, they had neglected the progress of the enemy troops. This would lead to surpising developments.

The Spanish Reaction

News of the large-scale embarkation at Dordrecht reached Velasco on June 20th. He imme-diately started to march south and reached Maastricht on June 23rd, where orders from Albertus directed him towards Langerbrugge (near Gent), where he would be expected on June 29th with 9 regiments/ 102 comp of foot and 15 comp of cavalry. Velasco sent the greater part of his army directly to Langerbrugge and together with 23 comp foot and 2 of horse he set out to Oudenburg.

Albertus meanwhile tried to rally the mutineers and succeeded in pursuading 1.400 foot and 600 cavalry to join him at Langerbrugge.Also from the deserted schansen surrounding Oos-tende, from Sluys and Gent as well as some other garrison places some 24 comp of foot came to Langenbrugge. Friday 30th June the Archduke marched to Brugge, where he was joined by another 6 com-panies of foot and 5 of cavalry. Also he lent 5 halfcannon and I field-piece from the garrison.

The Archduke had now under his command:

- 112 comp foot, of which 14 comp rallied mutineers; ± 8,700 men.

19 comp regular cavalry and in addition some 600 rallied mutineers; ± 1,400 men.

6 artillery-pieces.

Velasco remained with part of his army, meanwhile reinforced by 9 comp foot of Warenbon's Burgundian regiment, near Oudenburg: a total of ± 3,000 foot and 200 cavalry.

In the early morning of July 1st the Spaniards marched to Oudenburg, where the schans was easily retaken. Meanwhile the schansen of Bredene and Plassendael had been deserted by the States' army. The advance-guard was ordered immediately to Nieuwendamme. The Archduke himself, with the bataille and rearguard, marched to Leffinghe, reaching it at 8PM.

In the early morning of July 1st the Spaniards marched to Oudenburg, where the schans was easily retaken. Meanwhile the schansen of Bredene and Plassendael had been deserted by the States' army. The advance-guard was ordered immediately to Nieuwendamme. The Archduke himself, with the bataille and rearguard, marched to Leffinghe, reaching it at 8PM.

Preliminary encounter at Leffinghe

The delegation of the States-General in Oostende at first ignored the rumours about the Spanish threath, untill the expelled garrison troops from the schansen arrived. So Maurits first heard about the vincinity of the Spanish army in the evening of July I st. Maurits realised that, since the schansen which had to slow down or even stop the advance of the Spanish army had been deserted and without the roads and river-crossings at Leffinghe being destroyed, the way to Oostende lay open for the Spanish army.

Now he had to decide upon how to react to this unexpected surprise:

- Not risk his preciously trained troops in a bloody battle, but take a defensive position behind (south of) Nieuwpoort harbour and keep the way to Duinkerken, their original mission, open.

- Attack the enemy, in order to keep the connection with Oostende open, from where the badly needed supplies for his troops and intended sieges would have to come.

He decided for the attack. He intended to prevent the Spanish army to pass Leffinghe, thus keeping the connection with Oostende open and occupy the schans at Nieuwendamme to prevent an attack from the direction of Dixmuide/Veurne.

Count Ernst van Nassau was chosen to stop the Spanish advance at Leffinghe. At 5 AM in the early morning of Sunday July 2nd, Count Ernst crossed Nieuwpoort-harbour. He departed with part of his command, the rearguard: 19 comp foot/ 1.700 men, 4 comp horse/350 men and 2 halve-cannon (drawn by 40 horses!); about the strength of the enemy-force they expected to meet. Occupying the Leffingherdijk and keeping the enemy East of Leffinghe, would give Maurits time to cross the harbour with all his troops at low tide, between 8-10 AM. The remainder of the rearguard stayed north of the harbour to guard the approach route by way of Nieuwendamme, where the schans was occupied by 150 men.

For a detailed description of this encounter, I once again refer to Arquebusier, since I want to head along towards the final encounter at Nieuwpoort. What followed can hardly be called a battle. It became a massacre that seems to have lasted not much more then half an hour, some-where between 8:15AM and 9:00AM. The Spanish bataille, consisting of 3 tercio's/regiments, between 2.400 and 3.000 men and between 3.300 and 3.900 cavalry, received some artillery shots from the States' troops which were deployed behind Mariakerke. However at the first signs of attack Count Ernst's men all routed and were slaughtered. The Spanush rearguard, counting some 3.000 foot and all the artillery, even didn't have to come into action. The van-guard had not yet returned from it's march to Nieuwendamme, where it had encountered the same problems as Prins Maurits 2 days before.

Reinforcements from Oostende, counting about 900 foot and 100 horse from the garrisons of the previously deserted schansen, cowardly halted at the schans Albertus. About 800 men of the States' army are were killed, of which 600 men out of 1.100 from the Scottish regiment.

Count Ernst was blamed by the States to have spoiled so many costly lives from Prins Maurits' army and to have endangered the entire expedition by the bad handling of his command. Although Count Ernst may be accused of being an incompetent commander, he actually does have slowed down the Spanish advance. It is estimated that the action at Mariakerke, the rallying of the Spanish troops and the consultating by the Archduke of his subcommanders about what step to take next, has caused a delay of about 3-4 hours. Perhaps the greatest mistake was made by Maurits, by not ordering to destroy the repaired roads around Leffinghe, after the States' army had passed by.

The Archduke was inclined to take first the schans Albertus, in order to cut off Maurits' from Oostende. As Maurits would be devoid of supplies from Oostende, this might force him to raise the siege of Nieuwpoort soon and seek battle with the Spanish army to fight his way out.

This battle might occur then under favourable circumstances for the Spaniards. It were the younger commanders, led by the Walloon colonel La Barlotte, who persuaded him to loose no time and seek battle at Nieuwpoort with the demoralized enemy. However to secure his back he ordered Velasco to stay at Oudenburg with over 2.000 men, to prevent being fallen in his back from the direction of Oostende and to guard the baggage as well.

Preparations for the Final Encounter

The Spanish advance-guard had meanwhile returned with nothing achieved from Nieuwendamme and rejoined Albertus' army. It was not before about 10.30AM that Albertus had gathered his troops on the beach between Mariakerke and Ravesijde and that he gave the signal to march towards Nieuwpoort.

To prevent being surprised from either side Maurits ordered the admiral of the fleet on July 2nd at SAM (high tide) to start the construction of a ship-bridge across the harbour.This to allow both parts of the army to move quicker from one side to another, in case of an attack from either side. All other ships and boats had to leave the harbour.The boats would be useless for a large-scale embarkation in case of a defeat and they also shouldn't fall into the hands of the enemy.

The harbour actually was formed by the mouth of the River IJzer, which at low tide was nothing more than a gully, meandering its way through muddy banks. At high tide it was about 12 feet deep and only crossable by boat or bridge. At the south bank of the harbour 2 light-towers were situated. A larger one towards the town and a smaller one towards the sea, at the junction of 2 dikes. The latter was enclosed by a schans which had been constructed by the Spaniards, but deserted at Maurits' approach. The tower served as an excellent watchingpost. About here the boat-bridge probably was constructed.The beach may at lowest tide have reached a breadth of up to 500mtr, while at high tide it may have been no more then between 10 and 25mtr. See MAP II for a sketch of the battlefield.

The harbour actually was formed by the mouth of the River IJzer, which at low tide was nothing more than a gully, meandering its way through muddy banks. At high tide it was about 12 feet deep and only crossable by boat or bridge. At the south bank of the harbour 2 light-towers were situated. A larger one towards the town and a smaller one towards the sea, at the junction of 2 dikes. The latter was enclosed by a schans which had been constructed by the Spaniards, but deserted at Maurits' approach. The tower served as an excellent watchingpost. About here the boat-bridge probably was constructed.The beach may at lowest tide have reached a breadth of up to 500mtr, while at high tide it may have been no more then between 10 and 25mtr. See MAP II for a sketch of the battlefield.

The dunes were of modest hight, the highest up to 15mtr. Several dunes were connected by ridges, others were seperated by 'valleys'. On the landside of the dunes was a strip of some 200mtr breadth called the greenway, flanked by agricultural fields, the only terrain suitable for cavalry actions.

At 8 AM 5 comp cavalry under Lodewijk Gunther van Nassau, general of all cavalry and also a nephew of Prins Maurits, crossed the harbour. They had to wade through 2 m deep water. Meanwhile Maurits awaited at the schans the finishing of the boat-bridge. Between 8 and 9AM Spanish troops were reported entering the beach at Ravensijde and captured Spanish troopers informed Maurits about the Dutch defeat at Leffinghe.

At about 9AM Maurits sent Vere with the vanguard and 2-24pdr guns across the harbour, still through between 1 and 1 1/2 mtr deep water. Vere had orders to take positions on the north side of the harbour to await the enemy. From Vere's commentaries one can read that during this phase he created a kind of forlorn hope of mainly musketeers out of his vanguard and placed them on some advance dune-tops and on a dune-ridge on the right flank. Not clear to me is whether the deployment of the forlorn hope was maintained during the final deployment. On my map showing the final deployment I have indicated them seperately.

At about 10AM the remainder of the van and part of the wagon train crossed the boatbridge, which had just been finished. At about 10.30AM the bataille, now under Solm's command, crossed the harbour too and probably also the remainder of the train; part of them across the boat-bridge and part through the rapidly falling water.

The rearguard stayed behind yet behind for a while at the schans to watch the town from that side and to protect the bridge and some stranded boats. So did the remainder of Count Ernst's command, also part of the rearguard, to watch the town from the side of Lombartsijde. Four 24-pdr guns and part of the train were removed from Lombartsijde to the beach.

It was about 11:00AM as a detachment of Spanish cavalry advanced to test the Dutch army. Before they could be lured into an ambush by Gunther Lodewijk's cavalry, several premature salvo's by the Dutch artillery revealed their intention and position, what allowed the Spanish cavalry to evade into the dunes. At 11.30 Albertus halted the advance, perhaps to allow his men some rest and to consult his commanders once more. As the Spanish army arrived within sight of the enemy, time neared I 2AM.AIbertus also deployed his troops on the beach, while the artil-lery was moved to the front.

Maurits considered an all out battle the only way out, despite some more conservative advises from Vere. This does not mean he became reckless, since carefullness was one of his most famous characteristics. Concluding from Albertus' movements a Spanish full-scale attack from that side was inevitable, he ordered the rearguard across the boat-bridge and to start breaking down the bridge. Also the troops from Lombartsijde now joined the rearguard.

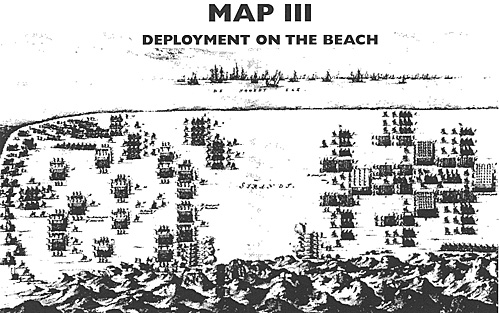

Both armies were deployed on the beach now. Deployment most probably will have been as shown by MAP III. Although not quite contemporary, I think it corresponds with most reliable accounts.

Both armies were deployed on the beach now. Deployment most probably will have been as shown by MAP III. Although not quite contemporary, I think it corresponds with most reliable accounts.

Final Deployment

For a time-span of 2 hours the Spanish army stayed in place on the beach, within sight of the States' army. Meanwhile however tide had passed it's lowest point and the sea-level was rising again, herewith narrowing the beach. Moreover the Dutch ships fired some salvo's between 1.30PM and 2.00PM. This fire was answered by part of the Spanish battery, upon which the ships retired. Albertus was forced now to make an almost complete side-move into the dunes, with Maurits following his example.

Of the Dutch battery 4 guns were kept on the beach, closely protected by I English battalion. The remainder of the van was placed in the dunes to the right of the battery, with the English regiment in front and the Frisian regiment behind them, both in 4 battalions. Part of the van was deployed to the front (see my before-mentioned remark on the deployment by Vere of the forlorn hope). On a higher dunetop to the far right from where the greenway could be cove-red, 2 guns of the battery were fixed in place on wooden platforms, to prevent them sinking in the loose sand. The bataille was also deployed in 4 battalions, in 2 lines, a bit to the rear-right of the van, overlapping the far right battalion of the van.

The rearguard was deployed to the rear-left of the bataille, more inward the dunes again, in 4 battalions in 1 line, actually covering the vanguard and with its far right battalion overlapping the far left battalion of the bataille. The cavalry was completely moved to the far right, opposite the Spanish on the greenway, except for the 7th squadron, which was held in reserve to the rear.

Maurits with his staff probably was to be found in the vincinity of both the bataille and the cavalry. Maurits is said to have been accompanied by a core of young noblemen from several countries, many of them to learn about Maurits tactics. Mentioned are his 16 year old brother Frederik Hendrik (his later successor) who was on his first military mission, the German Fiirst Johan Ernst von Anhalt, the German Duke of Holstein, the Counts Albert and Hendrik van Solms, Lord Grey of Wilton, Henry de Coligny Count of Chatillon, John Drury, Justinus van Nassau and Sir Philip Sydney, who fled on a boat before the battle had even started.

The van of the Spanish army took position on the right wing, the place of honour and was to stay on the beach. It consisted of the mutineer horse and foot under their own commanders or 'Eletto' and under the overall command of Mendoza. The van was deployed behind the artil-Iery.The bataille in the centre, commanded by Albertus himself, contained the Spanish tercio's of Monroy, El Villars and Zapena, the Italian tercio of d'Avalos and his Dukal cavalry Guard. The rearguard on the left wing comprised the foreign elements of Albertus' army: the Walloon, Irish and German troops. The rearguard was commanded by the Walloon colonel Barlotte probably with the Walloon colonel Bucquoi as second in command. Both the bataille and rearguard stood in the dunes, with the rear on the edge of the greenway.

On the far left the 'regular' cavalry under Galeno had taken positions.

The final deployment of both armies is shown on MAP IV. Numbers and letters correspond with the ones on the now following OOB. This map appeared in the 'Nassauschen Laurencrans' in 1610. Probably it is copied from the almost (and as far as I know only) contemporay drawing made by Floris Balthasar in 1601, on request by the States-General.

Good Generals Need Some Luck

- Road to Nieuwpoort: 2nd July 1600

Map 1: The Road to Nieuwpoort

Jumbo Map 1: The Road to Nieuwpoort (slow: 185K)

Battle of Nieuwpoort: 2nd July 1600

Map 4: Battle (slow: 135K)

Jumbo Map 4: The Road to Nieuwpoort (extremely slow: 356K)

Order of Battle

Color Illustrations (very slow: 247K)

Wargaming the Battle

Back to Battlefields Vol. 2 Issue 1 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com