When, in 1824, the first British adventurers arrived at Port Natal, on the coast of south-east Africa, they found a still, quiet lagoon, teeming with hippos, surrounded by a sandy shore fringed with mangroves and sub-tropical bush. This image seems a world away today; seen from the air, as the plane circles low over the corrugated green hills, covered with sprawling development, on the final approach to Durban, the jaws of land surrounding the bay remain the same, but the Robinson Crusoe lifestyle of those early settlers has long since been swamped by the bustling modernity of a modern African city.

Durban is now a vibrant and varied community, whose population and architecture reflect its chequered history. In 1824, the dominant local power was the Zulu kingdom, whose heartland lay fifty miles further north, across the Thukela river. The original earthwork fort built by those first settlers, grandly named Fort Farewell, after their leader, an ex-Naval officer, lies somewhere beneath the pavements right in the heart of the city, and only the street names recall the passing of those piratical pioneers.

The bay was secured for Britain by grant from the Zulu kings, and the grand old Colonial buildings in the city square reflect the fact that Natal was a British Colony for nearly seventy years. A kaleidoscope of Imperial statesmen and soldiers passed through the harbour at one time or another, often on their way to confront the many tensions that arose out of the country's conflicting ethnic and political make-up.

Winston Churchill was among them; as a young reporter he had been captured during the early stages of the Boer War. He escaped, and a plaque outside what is now the main post office recalls that he gave a rousing speech there on his return. So, too, was Mahatma Ghandi; the British imported Indian labour in the 1860s, to work the sugar-cane fields, thus adding another layer to the rich cultural mix; Ghandi practised as a lawyer among Natal's Indian community, and it was in the provincial capital, Pietermaritzburg, that he was thrown off a train one night for having the wrong ticket, and, sitting lonely and vulnerable on the station, first conceived his strategy of peaceful resistance to British rule. It is ironic that the origins of one of the most successful non-violent revolutionary movements in recent history lie in a country which, until recently, was a by-word for the suppression of human rights; yet South African history is nothing if not rich in irony.

The 1879 Anglo-Zulu War is just one of a number of over-lapping conflicts which characterise this history, a three-way struggle between indigenous African groups, the British, and the Boers. This conflict left its mark early on Port Natal, which was the only practical harbour in the region, and the gateway to the hinterland; in 1842, the British and the Boers, fought it out on the very shores of the lagoon.

'Some corner of a foreign field.' British graves near the Coastal Column's base at Fort Pearson.

'Some corner of a foreign field.' British graves near the Coastal Column's base at Fort Pearson.

The British mounted a surprise night attack on a Boer camp, but were spotted and ambushed as they marched along the beach at low tide. The mangrove-lined sand-dunes of the site of the Battle of Congella have long disappeared, but the heavy stone monuments which mark the spot where the British dead were buried still remain.

In the aftermath of the battle, the British were besieged in an earthwork fort - the site is still known as The Old Fort today - and a local settler, Dick King, slipped through the Boer lines and rode 600 miles to the nearest British outpost to raise the alarm.

The remains of the impressive trenches which surrounded Col. Pearson's fort at Eshowe.

The remains of the impressive trenches which surrounded Col. Pearson's fort at Eshowe.

A warship sailed up to lift the siege, and Natal was secured for Britain; a statue of Dick King now stands on the esplanade, commemorating his ride. Any traveller seeking to follow in the steps of this history is still best advised to begin at Durban; it is possible to start at the other end, from Johannesburg inland, but Durban offers a sense of historical context, of the beginning of the story.

Here the destinies of the British and the Zulu kingdom first became entwined, and the road to the Zulu War truly began. Durban, moreover, boasts a very good Local History Museum which, at the time of writing, is preparing a major Zulu War exhibition, which will be open in 1997.

Inevitably, most visitors who come to South Africa in search of the Zulu War are drawn by the drama of its two most famous actions, Isandlwana and Rorke's Drift. Rorke's Drift lies about four hours drive from Durban, via Pietermaritzburg and Greytown, but, if time allows, it's best to resist the temptation to go there direct.

Far better plan a circular route that saves these sites as the climax of the trip, to build up slowly, savouring as much else as you can, because the melancholy grandeur of Isandlwana is difficult to follow. Instead, travel on the main tarred highway up the coast, a route which happily allows you to journey through a little of the early history of the Zulu kingdom, and start a battlefield tour at the point where the War began.

Natal's coastal belt is sub-tropical and humid, and the road cuts up through hills coloured a uniform bright green by sugar cane. In the early days, the Zulu Kingdom's border was fluid, and a number of place-names recall the fact that King Shaka, the nation's founder, had settlements south of the Thukela River, the traditional border.

Shaka's Kraal and Shaka's Rock, on the coast, both have romantic and largely spurious stories linking them to the great king, though there is no denying his link with the modern town of Stanger. Stanger was built where his KwaDukuza homestead once stood, and it was here in September 1828 that Shaka was assassinated; a monument, erected in the 1950s, marks the spot where he lies buried, and nearby is a rock on which he is said to have sat and sharpened his spears.

It is a short drive from Stanger to the Thukela. Near its mouth, below a knoll on the Natal bank, can still be seen the withered stump of the tree beneath which, in 1878, British representatives delivered an ultimatum to the Zulu king's envoys. The terms of the ultimatum were deliberately harsh, and the Zulus could not comply; a month later one of the most famous of all the British Colonial Wars began.

The tree survived into the 1980s, when a severe flood damaged its roots, and, despite the best efforts of conservationists, it perished. Today the site is further marred by a motorway bridge in the final stages of construction, which spans the river at the very spot where ferries once transported British troops across the border.

Fort Pearson

On the knoll overlooking it, however, the trenches of a British outpost, Fort Pearson, can still be seen. This was the starting point for one of three invading British columns, the Right Flank Column, under Colonel Charles Pearson. The Lower Thukela offered one of the best practical routes into the old Zulu kingdom, and as a result achieved such strategic importance that it was fought over several times; from the summit of Fort Pearson, one can clearly see Ndondakusuka hill on the Zulu bank, the site of not less than two battles.

In 1838 a combined force of British traders and black auxiliaries crossed into Zululand at the Lower Drift, but were met by a strong Zulu force coming in the opposite direction. Despite the traders' firepower - this battle was one of the first contests between troops armed with firearms and the Zulu army - the trader army was overwhelmed, pushed back against the river, and slaughtered.

King Cetawayo of the Zulus.

In 1856, on almost exactly the same ground, the rival Princes Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi fought to secure the Zulu succession, and Mbuyazi's force was similarly trapped and massacred.

King Cetawayo of the Zulus.

In 1856, on almost exactly the same ground, the rival Princes Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi fought to secure the Zulu succession, and Mbuyazi's force was similarly trapped and massacred.

Historic ground indeed; the modern road still takes today's visitor broadly in the bloody footsteps of these contesting armies. Fort Pearson itself remains an impressive sight, a worth while jumping-off point for an invasion; although the remains of Pearson's redoubt are surprisingly small, the knoll drops away so steeply down to the river that any Zulu attack from that side would have been quite impossible.

Pearson's Column had its fair share of adventures during the course of its operations. Early on the morning of January 22nd, the Zulus attempted to block his advance at a line of hills above the Nyezane River, but, despite being caught on the move, Pearson drove off their attack.

Eshowe

The grave of Pte. Walter McLeod of the Buffs, one of those who died of disease during the seige of Eshowe.

The grave of Pte. Walter McLeod of the Buffs, one of those who died of disease during the seige of Eshowe.

He advanced a few miles further to the deserted mission station at Eshowe, where he received news that the Centre Column had been heavily defeated at Isandlwana. Left unsupported, unable to advance but reluctant to retreat, Pearson dug in at Eshowe, and for the best part of three months his Column was besieged by the Zulus.

With no communication equipment, Pearson's men were cut off from the outside world, constantly harassed by the enemy, cooped up in an insanitary earthwork, with food running short.

Not until the beginning of April did the senior British commander, Lord Chelmsford, manage to collect a relief column at the Thukela, and fight his way through to relieve Eshowe, defeating the Zulus again at Gingindlovu.

Lord Chelmsford.

Lord Chelmsford.

Gingindlovu

The modern traveller, driving up from the Thukela, will encounter the Gingindlovu battlefield first, right beside the main North Coast Road. This area, too, is under heavy sugarcane cultivation, and there is little to mark the battlefield apart from a large stone cross, and a number of British military graves nearby.

Often, when the sugar-cane is in full growth, it is almost impossible to get any impression of the lie of the land. At first glance, this comes as something of a disappointment, but if you are lucky enough to be there when the cane has been cut, it is easy to see that Lord Chelmsford had picked an ideal site for his position. He arranged his force in a hollow square on top of a low rise, from which the ground falls away on all sides, opening out onto a view of the Eshowe heights in the distance.

Visibility must have been excellent indeed, on the day of the battle the Zulus were spotted while still several miles away -- and the Zulus were faced with an uphill assault across ground raked by fire on all sides.

Nonetheless, Gingindlovu was still a close contest, for the Zulus realised that the weakness of the square lay in the corners, and their determined charges reached to within twenty yards of the angles before being cut down. Gingindlovu is an important battle, somewhat neglected.

A few miles beyond Gingindlovu, the road begins to climb the Eshowe heights, passing as it does through the site of Pearson's victory of 22nd January. The battle of Nyezane is a particularly interesting engagement, a fluid action very different from the popular 'turkeyshoot' image of the later Zulu War battles. Pearson's column had just crossed the Nyezane river, and was toiling up the hills, when the Zulus attacked.

British columns were particularly vulnerable on the move, and the Zulu attack might have proved disastrous, had it not been triggered prematurely. The Zulus failed to deploy properly, only one wing - the right horn - coming into action. Pearson spread his men out in a screen to protect his convoy, and drove the Zulus back in line. Today, at the very least, the visitor needs to have with him a good map, because it is difficult to work out where all this happened; indeed, Nyezane, like several other local sites, is often best visited for the first time in the company of an experienced guide who can point out the landmarks.

A stone cross, hidden now off the road, marks the site of the British dead, and a foot-track runs along the spur up which the British advanced. Here, on a knoll occupied now by a Zulu homestead, Pearson anchored his defence, facing his line against a steep hill opposite, known as Wombane. The knoll is little more than a rise, but despite the disfigurement caused by the modern road, it is easy to see it was a commanding position. Immediately below it, the ground drops into a gully before rising up to Wombane; although hidden to some extent by long grass and bush, the attacking Zulus would have been horribly exposed as they ran down the slope of the hill. Little evidence of the fight survives, but on a quiet day, when the roar of passing traffic doesn't spoil the concentration, it is still possible to conjure up images of that fight; the crashing volleys from troops on the knoll, the chatter of Gatling fire, the boom of guns and screech of rockets and, on the slopes opposite, the darting figures of the Zulus, masked by bush and wreathed in smoke.

Although the battle was a British victory, it was at Nyezane that the British learnt for the first time that, in the words of one veteran, fighting the Zulus was 'terribly earnest work, and not child's play'.

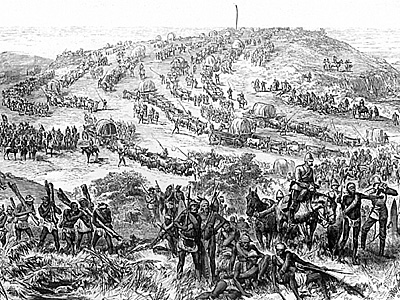

The relief column marching to Eshowe. The wagons travelled four to six feet abreast to reduce the length of the convoy.

The relief column marching to Eshowe. The wagons travelled four to six feet abreast to reduce the length of the convoy.

Eshowe today is a fair-sized town, catering largely for the agricultural industry. There is a nice museum in the town itself, housed in a old fort built as a barracks for the Zululand Native Police in the 1880s. The exhibits include a good selection of military artefacts, including shields and spears, and displays relating to Zulu life and the 1879 campaign. The site of Pearson's old fort lies on its outskirts; nothing remains of the mission he occupied, though the buildings' foundations can still be traced in the grass.

Most of the high rampart which surrounded the post still survives, however, though the ditch is filled here and there with bush. In it's time, it was clearly a very formidable entrenchment, and certainly impregnable against an enemy lacking artillery. On a slope nearby, the graves of Pearson's men who succumbed to disease - the biggest killer of the coastal campaign - lie undisturbed, a mournful patch of neat iron crosses sprouting from the long grass.

Accommodation is not plentiful at Eshowe, but just outside lies Shakaland cultural centre which, despite its tacky name, offers the chance to stay a night in traditional grass huts - with all mod-cons added - and explore something of the Zulu lifestyle through well-staged traditional dances.

Here Zulus in traditional dress also demonstrate something of the old Zulu fighting techniques, hurling light throwing spears at shields set up as targets, or miming the fierce close-quarter tussles with the stabbing spear.

More Visiting Zululand

-

Visiting Zululand Part 1: Fort Pearson, Eshowe, Gingindlovu

Visiting Zululand Part 1: Ulundi

Visiting Zululand Part 1: Hlobane, Khambula

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 8 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com