Hlobane

Today, Hlobane remains one of the most fascinating and inaccessible of the Zulu War battlefields. A main road runs just below the mountain, which is a flat-topped plateau about four miles long, but, despite the presence of a colliery on the lower slopes, the summit can only be reached by those prepared to strike off on foot.

Here, too, it is a good idea to go with someone experienced, since the battle ranged from one end of the mountain to the other, and it is easy, not only to loose track of the battle, but to get physically lost. Hlobane is surrounded by cliffs on all sides, with potentially disastrous results for the unwary.

The easiest way up is to follow a mine track which cuts up through the cliffs which line the summit not far from where Captain Campbell and Mr Lloyd, two of Wood's Staff, were killed. Their graves are still surrounded by a neat stone wall, built shortly after the war, though the site is often hidden by long grass. Both were killed by Zulu snipers hiding in the cliffs above; Campbell had led a sortie to flush the Zulus out, and was killed at the mouth of a deep crevice between the boulders. These boulders can be seen from his grave, though it is unwise to search out the cave itself, since rock-falls over the years have made the spot unstable.

The lonely memorial which marks the graves of Campbell and Lloyd on the slopes of Hlobane Mountain.

The lonely memorial which marks the graves of Campbell and Lloyd on the slopes of Hlobane Mountain.

The surface of Hlobane is an undulating crazy-paving of boulders, weathered almost flat by aeons of wind and rain. Apart from a radiomast, erected by the mine, the summit has hardly changed at all since Wood's irregular cavalry skirmished there with the Zulus.

Having once got up the mountain, the British found themselves trapped, caught between warriors on the mountain itself, and a much larger army which was on its way to attack Wood's base at Khambula, and which appeared, largely by coincidence, at the foot of Hlobane once the battle had begun. Most of the horsemen were driven to the western end of the mountain; one group tried to descend by the route they came up, were caught against a cliff-face, and wiped out.

The terrible 'Devil's Pass, centre, on the western end of Hlobane, a staircase of

rock down which the British were forced to retire under severe Zulu pressure.

The terrible 'Devil's Pass, centre, on the western end of Hlobane, a staircase of

rock down which the British were forced to retire under severe Zulu pressure.

For the rest, the only way off was a steep rocky slope, a staircase of boulders two hundred feet high. This was the terrible 'Devil's Pass', down which the horsemen had to descend, whilst the Zulus rolled boulders down after them, sniped at them, or clambered between the rocks to pick off stragglers, turning the retreat into a rout.

The British were chased from the field, leaving over 70 dead behind. At first, it seems absurd that anyone could have contemplated attacking the summit with cavalry, but the British gambled that, once on top, the summit was sufficiently flat to allow them free reign. Up to a point, they were right, although the surface is much rougher than it must have appeared from a distance, and riding across it must have required a good 'seat'!

Indeed, the summit of Hlobane is something like a table, with the cliffs around the edges representing the sides; for a while during the battle they did largely command the summit but, as the Zulus realised, the real trick was to command the way up and down, and as it proved there was no way off the table without tipping over the edge. Today, the 'Devil's Pass' remains an awesome spot, lonely, windswept and mournful, arguably the most atmospheric battle site of the war, after Isandlwana.

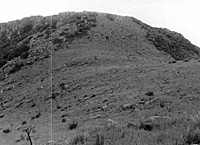

The northern slopes of Khambula battlefield. The Zulu iNgobamakhosi regiment attacked up this bare slope, sheltered by nothing but anthills, Colonel Wood's position was on the skyline, marked now by the clump of trees and the rise, left.

The northern slopes of Khambula battlefield. The Zulu iNgobamakhosi regiment attacked up this bare slope, sheltered by nothing but anthills, Colonel Wood's position was on the skyline, marked now by the clump of trees and the rise, left.

Khambula

Having defeated Wood's cavalry at Hlobane, the main Zulu army went on to attack Khambula the next day. Here, however, they found the British prepared, secure behind entrenched wagon-laagers and a small earthwork fort. For four hours 20,000 Zulus attacked Khambula on all sides, and on several occasions came within an ace of penetrating the lines. Yet in the end their extraordinary courage was no match for the storm of shot and shell poured into them, and they fell back. Wood ordered his cavalry after them, and the survivors of Hlobane took a terrible revenge in one of the most ruthless pursuits of the war.

The southern slope of Khambula; the British position was on the left, where the trees now stand, and the Zulus gathered in the dead ground, right. Two companies of the 90th sallied out, haltIngiust above the present Zulu homestead, and fired down into the Zulus, breaking up their concentrations.

The southern slope of Khambula; the British position was on the left, where the trees now stand, and the Zulus gathered in the dead ground, right. Two companies of the 90th sallied out, haltIngiust above the present Zulu homestead, and fired down into the Zulus, breaking up their concentrations.

Nearly a thousand Zulus were killed around the camp, and hundreds more along the line of retreat. Khambula was the first major defeat suffered by the Zulus in the course of the war, and, coupled with that at Gingindlovu on the coast a few days later, it had a devastating effect on their morale.

Khambula today is open farmland, hardly changed since 1879, apart from a plantation of trees on the site of Wood's wagon-laager. Wood's position was built on the crest of a ridge, with his redoubt on the high point, and a monument marks the spot where the remains of his ramparts can still be traced. To the north, the country slopes gently down to a plantation a couple of miles away; it was across this slope that the British provoked the Zulu iNgobamakhosi regiment into an unsupported charge. It seems astonishing, now, how anyone could have persisted in attacking across ground which offers no cover apart from a scattering of ant-heaps, yet the iNgobamakhosi actually reached the British wagons before being driven back, leaving the slope littered with dead and dying.

Now, it is the British dead who are remembered here, buried in a small walled enclosure half way down the hillside. To the south, the ground drops away sharply into a surprisingly steep valley, which was dead ground to the defenders. Here the Zulu centre and left could approach to within a few hundred yards of the British position, and they were only exposed to British fire as they emerged from the valley to make that final dash across the open.

This gave them a distinct advantage over their colleagues on the opposite flank, who had been fully in view across several miles of their approach. It was from here that the Zulus weathered a storm of fire and succeeded in capturing part of the British stockade. This position was so dangerous that at one point, to deny them this advantage, Wood sent two companies of the 90th Regiment out to line the lip of the valley and fire down into it; it was a bold and successful stroke, but the companies were horribly exposed to cross-fire, and were forced to retire with a number of injured, including their commander, Major Hackett, who was blinded by a Zulu bullet. Much of this cross fire came from a knoll which is readily identifiable today, although it seems an insignificant enough feature now.

Khambula is an easy battle to read, an ideal one for those who like to settle down in the centre of a battlefield and run through it step by step, whilst it is particularly rewarding for those who have half a day to spare, and are prepared to spend some of it wandering out to the outlying features. Since the battle was a British victory -- and a brutal and decisive one, at that -- there are no memorials here to the Zulu dead, which is something of a tragedy, since Khambula was the Zulu equivalent of Pickett's Charge - a high-water mark, where possible victory turned in an instant to the shocking prospect of defeat. It was at Khambula that the Zulu kingdom began to fall.

NOTE; Ian Knight is the author of a number of books on the Anglo-Zulu War, including Brave Men's Blood; The Epic of the Zulu War, Nothing Remains But To Fight; The Defence of Rorke's Drift, The Anatomy Of The Zulu Army and, with Ian Castle, The Zulu War; Then and Now, and Fearful Hard Times; The Siege and Relief Of Eshowe. His is also the author of Go To Your God Like A Soldier; The Victorian Soldier Fighting For Empire, and, with Professor John Laband, The War Correspondents; The Anglo-Zulu War.

He is also the Editor of our sister magazine 'Age of Empires', the next issue of which will be available June/July. He organises regular tours of the 1879 battlefields; anyone interested in joining one should write c/o Ian Castle, 49, Belsize Park, London, NW3 4EE.

More Visiting Zululand

-

Visiting Zululand Part 1: Fort Pearson, Eshowe, Gingindlovu

Visiting Zululand Part 1: Ulundi

Visiting Zululand Part 1: Hlobane, Khambula

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 8 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com