29th February

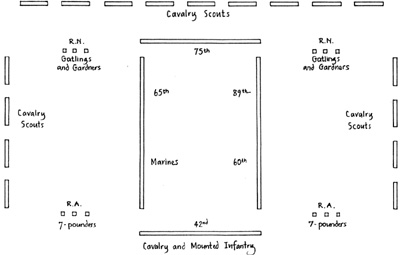

The British woke at 5 breakfasted and marched out of camp at 8 a.m., the men carried water and 1 day's rations. The transport was left at Fort Baker except for the 100 ambulance camels and animals carrying ammunition (say 100 mules). The whole force marched in a rectangle (see diagram) 250 yards by 150 yards, the officers and baggage in the centre. The guns were dragged by their crews, draught teams were not taken. 1 Squadron of the 10th Hussars covered the front and left, a troop of the 19th Hussars covered the right of the square. The remainder of the cavalry and mounted infantry marched to the rear of the square.

8.00 a.m. The force marched slowly stopping to rest the men through low hills of dense scrub. The Mahdists withdrew in advance of the square keeping a distance of 1,200 yards. The square received rifle fire from concealed Mahdists but at this range it had no effect.

9.30 H.M.S. Sphinx, anchored off Trinkitat fired off 4 rounds, the shells fell 1 mile short of the Mahdist position and she was signalled to cease firing lest the British scouts be hit.

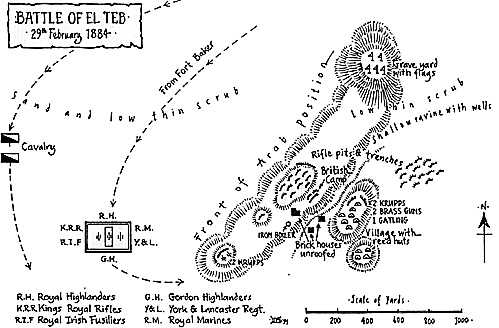

10.00 The Mounted Infantry were sent ahead to contact the Mahdists. Mahdist entrenchments were discovered around the village of El Teb. 2 Krupp guns and 1 brass howitzer were dug in to the South of the Mahdist line and 2 more Krupp guns, 2 brass howitzers and 1 Gatling to the North. These guns were manned by Egyptians who had been part of the garrison of Tokar.

11.20 British square halted 800 yards from Mahdist lines, coming under rifle and cannon fire. The square withdrew North East to a range of 900 yards and opened fire at the Southern Mahdist batteries with artillery and machine guns.

11.45. The Mahdist fire was silenced. The square then advanced with its' left face (Marines, 65th) towards the Mahdists. The top and bottom of the square (as depicted in the diagram) were now advancing in columns of fours behind and to the sides of their front line. The advance was steady, firing on the move.

The Mahdist defence was scattered in groups which made rushes towards the front of the square. The York and Lancaster Regiment (65th) recoiled 30 yards from a rush of hundreds of Mahdists. A corner of the square was opened which was closed up before any Mahdists could exploit the gap. Mahdist spearmen and British sailors (machine gun detachment) fought hand to hand.

When the Mahdist guns were close the square stopped to dress ranks and rushed the position. Amongst the first in were members of the Black Watch (42nd) indicating that the sides of the square fell on as well as the front face.

12.20 The British now wheeled out their Krupp guns and silenced the Northern Mahdist battery. They then moved Northwards to roll up the Mahdists in the village of El Teb and defending the Northern battery. The square formation was broken up into an irregular convex line with the 42nd, Marines and 65th holding the centre slightly in advance of the other Battalions. The sugar factory (brick house on map) and iron boiler proved strongpoints of the Mahdist defence aided by scattered rifle pits.

12.20 The British now wheeled out their Krupp guns and silenced the Northern Mahdist battery. They then moved Northwards to roll up the Mahdists in the village of El Teb and defending the Northern battery. The square formation was broken up into an irregular convex line with the 42nd, Marines and 65th holding the centre slightly in advance of the other Battalions. The sugar factory (brick house on map) and iron boiler proved strongpoints of the Mahdist defence aided by scattered rifle pits.

The sugar factory walls were too thick for the British guns to knock down so the Mahdists were driven out by the Marines using rifle and Gatling fire.

Simultaneous with the shelling of the Northern battery the British cavalry detected large numbers of Mahdists in the plain to the East of El Teb. The cavalry drew up in 3 lines, 10th Hussars, then 19th Hussars and a further 100 men of the 10th Hussars in the rear.

'Charge of the 10th Hussars at El-Teb', by Godfrey Douglas Giles 1884

'Charge of the 10th Hussars at El-Teb', by Godfrey Douglas Giles 1884

The cavalry lines maintained a gallop for 3 miles splitting the Mahdists into 2 groups. The 1st 2 lines overtook some of the Mahdists and ordered a halt. At the same time the 3rd line was attacked by at least 100 mounted Mahdists and a greater number on foot who had been concealed in the undergrowth. The 2 other lines turned around so that the 19th Hussars were in front and the 10th behind. The 19th Hussars; were assaulted by 30 more Mahdist cavalry who were driven off and lines were harassed by spearmen leaping up from hillocks and mounds of sand. The Hussars charged through the groups of soearmen, wheeling around and back while firing at the Mahdists.

14:00 Northern battery taken without further Mahdist resistance. Mahdist fugitives seen streaming towards Tokar (West) and Souakim (North)

Results

Out of about 4,000 men engaged, the British lost 30 killed and 159 wounded. 13 of those killed were in the cavalry action.

About 3,000 Mahdists defended El Teb and another 2,000 were held in reserve and attacked by the cavalry, with 825 bodies counted on battlefield.

The British camped at El Teb. 500 of the 42nd were left at El Teb where they guarded the supplies and buried the dead from Baker's defeat. The rest of the force marched to Tokar on March 1st. The Mounted Infantry and 10th Hussars were fired on as they approached Tokar but when the column drew near it was discovered that the rebels had fled. The main column camped on the plain in front of Tokar. On March 2nd the cavalry rode on to Debbah from where Tokar had been besieged.

The Mahdist camp at Debbah was empty, a Gatling and a mountain gun were, captured together with 1,500 rifles and ample ammunition.

The British did not attempt to hold on to Tokar but withdrew with most of its' inhabitants -- some 700 people. Amongst these were members of the garrison who had deserted to the Mahdists, but no action was taken againg this act. The whole force embarked for Souakim on March 5th.

Key Points

The number of Mahdists involved is based on eyewitness estimates of up to 10,000, orless than 5,000. The reserve was unable to overpower a force 1/3rd its size in terrain not suited to cavalry , One woman was reported amongst this group indicating a number of camp followers. The Mahdists had access to all the rifles left behind after Baker's defeat and the fall of Tokar, certainly enough for one for every Mahdist entrenched in El Teb. Accounts of Mahdist attacks concentrate on thrown spears and charging fanatics. Rifle fire is mentioned but clearly the vast majority of Mahdists did not use rifles. Any Mahdist accustomed to using firearms could have had a rifle. Professional slave traders, their guards and ex-members of the Egyptian army (if trustworthy) would be armed. The guns at El Teb were crewed by their original teams, 1 survivor claimed that he and 7 others had been dragged by ropes to the battle.

Overall odds for the British were about 1:1 or 1:2, high for a trained army fighting tribesmen but low for an assault on a fortified position. The decision to attack in square reduced available rifles by 3/4 although the guns were run outside the square when required. The Mahdists' stance protected the wells and village of El Teb but showed poor use of ground and resources. The 2 gun positions were sited such that they could not support each other and were easily spotted by the British.

The Southern position was stormed by a square formation that would have taken heavy casualties from an enfilading 2nd gun position or from Gatling and Krupps opening up unannounced at short range. The Gatling was prone to jam even under skilled crews however even a short burst would have had a serious effect on the British square.

'Bird's Eye View of the Battle of El-Teb

'Bird's Eye View of the Battle of El-Teb

The British took a large number of guns to El Teb and their crews were better trained than any the Mahdists could put together. It is no surprise that the Mahdists lost the artillery duels, they would have done better to hide their guns amongst the rifle pits and use them for a limited number of shots against the British assault.

The Mahdists adopted an organised defence, committing the majority of their local forces to a set piece battle. This decision enabled the British to defeat a large number of Mahdists in a single battle. The British army was trained in small wars against tribesmen and in regular conflicts against modern armies.

In 1882 they had defeated the modern Egyptian army by superior training and tactics. At El Teb the Mahdists were inferior to the old Egyptian army in weapons skill, they abandoned their advantages of surprise and fast movement by defending a fixed position. The British could have stood off and shelled the Mahdists but had to assault to prevent them slipping away and fighting another battle.

By moving the square across the Mahdist front and attacking from its flank the Mahdist ability to retreat was reduced. Being confronted by a flanking attack the Mahdists could have sat still, charged from their position towards the square (losing the benefit of their rifle pits) or withdrawn. With the British square between them and their base at Tokar withdrawal would not be easy.

Poor use was made of the Mahdist Northern gun battery which neither supported the Southern when it was overrun nor was it used against the British cavalry who were not supported by the artillery in the main square. No attempt was made to remove these guns when they were discovered not to be in a position to fire. By the time that the Northern guns were silenced the Mahdists were in a bad situation, their position had been outflanked and they had failed to break up the British square by spear assaults.

The Mahdist cavalry was inferior in numbers to the British but was acting in favourable terrain backed up by spearmen. The British cavalry beat off these troops at some loss, if they had been forced to withdraw considerable Mahdist forces could have fallen on the British flank as they were assaulting El Teb.

Campaign Options

The British shipped practically all of their available troops from Souakim to Trinkitat, fought a battle then sailed them all back again. There was no long term plan to subdue the area. The losses inflicted on the Mahdists were severe but no British force was to return to Tokar until February 19th 1891. Tokar was to become an important base for Osman Digma and the local Mahdists. Clearly the defeat at El Teb had no lasting effect on Mahdist support in the region.

The British could have left a garrison in Tokar supported by another at Fort Baker, half a battalion at each would compare with the old Egyptian garrison strength. If troops were left in the Tokar area Graham would have 1 less Battalion to act around Souakim but would reduce the overall support for Mahdism in the Eastern Sudan.

The population of Tokar was jubilant when the British marched in although they had also been ready to support the Mahdists. Many of the original garrison were still alive and could have served as local scouts for the British stationed at Tokar. The supplying of this garrison might have initiated future conflict. Provided that the British could march in supplies and beat off any attacks British prestige amongst the local tribes would continue to rise as Mahdist support fell.

The Mahdists gambled on a single large battle, they may have hoped that the strength of their defences would cause the British expedition to be abandoned. They lost the battle and the majority of their forces in the region. Half of the Mahdist force at El Teb was not engaged against the British square. This force could have been detached to hold Tokar forcing the British to fight 2 battles or placed on the hillside where it might threaten the flank of the square if it became broken up amongst the Mahdist rifle pits (as it did).

The Mahdists had most success when they shelled the British square before their guns were silenced and in the conflict with the isolated cavalry. The results of headlong rushes by spearmen against disciplined firepower were predictable.

References

The Egyptian Campaigns 1882 to 1885, Royle., C., London 1900

War In Egypt And The Soudan, Archer, T., Glasgow 1887.

Small Wars, Callwell, C.,by John Grehan

More El Teb

Back to Battlefields Vol. 1 Issue 8 Table of Contents

Back to Battlefields List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com