Thirteenth century Cairo glistened jewel-like along the Nile. The winter of 1260 had given way to spring and the first touch of the coming summer heat hung in the air. Most of the city's inhabitants went about their daily business unaware that anything special was happening. A few others gossiped, gesturing towards the Sultan's palace and speculating on the meaning behind the strange envoy that now had the attention of Sultan Saif Al-Din Qutuz and his generals.

Thirteenth century Cairo glistened jewel-like along the Nile. The winter of 1260 had given way to spring and the first touch of the coming summer heat hung in the air. Most of the city's inhabitants went about their daily business unaware that anything special was happening. A few others gossiped, gesturing towards the Sultan's palace and speculating on the meaning behind the strange envoy that now had the attention of Sultan Saif Al-Din Qutuz and his generals.

In the palace, Qutuz shifted uneasily in his chair and beheld the four men before him with a mixture of hatred and justifiable anxiety. The emissaries represented the Mongol prince Hulegu Khan and they laid before Qutuz a letter. It was not written in the tone by which one head of state normally addressed another:

- From the King of Kings of the East and West, the Great Khan.

To Qutuz the Mamluk, who fled to escape our swords.

You should think of what happened to other countries... and submit to us.

You have heard how we have conquered a vast empire and have purified the earth of the disorders that tainted it. We have conquered vast areas, massacring all the people. You cannot escape from the terror of our armies.

Where can you flee? What road will you use to escape us? Our horses are swift, our arrows sharp, our swords like thunderbolts, our hearts as hard as the mountains, our soldiers as numerous as the sand. Fortresses will not detain us, nor arms stop us. Your prayers to God will not avail against us. We are not moved by tears nor touched by lamentations. Only those who beg our protection will be safe.

Hasten your reply before the fire of war is kindled... Resist and you will suffer the most terrible catastrophes. We will shatter your mosques and reveal the weakness ofyour God and then we will kill your children and your old men together.

At present you are the only enemy against whom we have to march.

The Mongol ambassadors and Qutuz considered one another for long moments. Then Qutuz withdrew, commanding his Mamluk generals to follow him. The Mongols merely smiled.

The impromptu council of war was a somber affair as Qutuz's principal officers recounted the sober facts.

In 1253 Hulegu Khan, brother of the Great Khan Monge and a grandson of Ghengis Khan, had been told to gather his forces and move into Syria "as far as the borders of Egypt." His mission was to conquer and annex the lands as part of Ghengis Khan's schema - the entire world united under Mongol rule. Scholars debate the exact size Hulegu's force but it was enormous by the standards of the time. The ordu (horde) was comprised of approximately 300,000 warriors, who rode their ponies across the steppes to great effect. Adding women, children and other noncombatants the entire host numbered, by conservative estimate, about 2 million in all. It was not an army; it was more like a force of nature.

The Mongols arrived in Persia in 1256 and set about settling an old score. A few years earlier the Mongols had discovered a plot to send 400 dagger-wielding Assassins in disguise to their capital Qaraqorum with instructions to murder the Great Khan. It was a formidable task the Mongols had taken on, for over 100 years this Ismaili sect had terrorized the region. Their leader, Rukn ad-Din, was preceded by a herald, who declared, "Make way for he who holds the life of kings in his hands." The 200 Assassin fortresses, called "eagle's nests", were placed in inaccessible locations atop mountains and rocky crags and considered impregnable. Crusader princes, atabeqs, emirs and even Saladin himself had been forced to come to terms with them or suffer the consequences.

Now the Mongols moved through the Elbruz Mountains remorselessly seeking them out. For two years the Mongols moved from fortress to fortress with workmanlike efficiency. Chinese engineers set up siege engines and one by the one the "eagle's nests" fell. Hulegu showed no mercy; when a fortress was taken all the occupants, whether able-bodied men or babies in their cradles, were put to the sword. By the end of the campaign the Assassins were totally destroyed and Rukn ad-Din taken in chains to the Great Khan who had him executed.

The Assassins eliminated, Hulegu turned his attention to Mesopotamia and Baghdad. The Abassid capital was no longer the center of political power in the Islamic world, but it was still its intellectual heartland. Through a combination of Mongol skill, caliphal foolishness and treachery, Baghdad was captured, sacked and burned to its foundations in February 1258 (see sidebar).

Hulegu now fell back to Tabriz while the aftershocks from Baghdad's fall shook the entire Islamic world. Emirs and sheiks along the Mongols' line of advance came and did homage. One, Kai Kawus, gave Hulegu a pair of sandals with the emir's face painted on the soles so the Khan could walk on his face.

Among those offering an alliance to Hulegu was Hayton, the Christian king of Armenia. Hayton thought of the Mongols as a new Crusade to free Jerusalem from the Muslims. This perception was encouraged by Hulegu's chief lieutenant, Kitbuqa who was not only a Christian but claimed to be a direct descendant of one of the three Magi who had brought gifts to the baby Jesus. Following his visit to the Mongol leader Hayton sent messages to his Crusader neighbors that Hulegu was about to be baptized a Christian and strongly urged they too ally themselves with this new force and turn it to the Crusader cause.

Only Kamil Muhammad, the emir of Mayyafarakin, had defied the Mongols, responding to their envoy's demand for submission by crucifying him. Hulegu dispatched a part of his army to the town and quickly breached its walls. While Kamil Muhammad watched every living thing was killed. Then he was bound and pieces of his skin cut off, broiled over an open flame and fed to him piece by piece.

In September 1259 Hulegu moved again, gathering up all of Mesopotamia east of the Tigris in a lightning operation, then crossing the Euphrates on a pontoon bridge made of boats at Manbij. Word of the Mongol movement reached Sultan Al-Nasir, lord of Syria, who offered to submit to the coming army. Hulegu brushed it aside. Submission was not enough: the sultan was told he was "doomed to fall."

Al-Nasir organized the defense of Aleppo then fell back to prepare Damascus. The Mongol army, 300,000 strong, arrived on January 13, 1260. Engineers set up catapults and the city fell in a matter of days. Aleppo suffered Baghdad's fate. The men were put to the sword and the women and children were marched to the slave markets of Qaraqorum.

The city citadel, under the command of the elderly Turan Shah, held out for another month. Then, realizing there was no hope of rescue, it finally surrendered. In a rare act of compassion Hulegu ordered Turan Shah's life spared in recognition of his age and courage. The rest of the garrison was executed.

The fate of Aleppo rested heavy on Damascene minds and the citizens drove AI-Nasir out of the city, then sent their unconditional surrender to the advancing Mongols. Hulegu entered the city accompanied by Kitbuqa, Hayton and the Crusader Prince of Antioch, Bohemond IV, who had heeded Hayton's advice. A mosque was hastily converted to a church and a service celebrated there. Then Hulegu, with typical Mongol indifference to religion, forced Bohemond, a Latin Christian, to name a Greek Orthodox Patriarch religious head of Antioch.

Al Nasir fled towards Egypt but Mongol soldiers hunted him through Samaria, finally catching up with him near Gaza where he was captured and taken to Hulegu's court in chains.

Hard on their heels the Mongol envoys had come to Egypt and handed Qutuz a demand for submission.

Qutuz reflected on the situation. A proud, decisive man, he was not used to being addressed in terms of a coldly arrogant ultimatum. But he was also a realist; to his generals he admitted the Mamluks were probably no match for the Mongols. The commanders agreed and recommended capitulating to the Mongol demands

But Qutuz's own opinion differed. The Sultan had come to power by knowing how and when to act. Observing the dissolute and vapid character of the 15-year-old Ayubbid Sultan Nur al-Din Ali ibn Aibak in the face of the Mongol threat, Qutuz had deposed him the previous October. "Egypt needs a warrior as its king," he explained. To submit now would be an act of cowardice and treachery. He would not surrender, he defiantly told them. "If no one else will come I will go and fight the Tatars alone."

He barked out orders to his guards, who promptly seized the envoys. The Mongols, he knew, considered ambassadors to be untouchable. They treated those sent to them with utmost respect and expected theirs to be treated the same. To harm one they considered an act of unforgivable treachery.

Qutuz commanded the ambassadors be cut in half at the waist, and then decapitated and their heads placed on Cairo's great Zuwila Gate. The Mamluks were now bloodily and irrevocably committed to war with the Mongols.

THE MONGOL RESPONSE

In mid-February Hulegu's vast army once again began to stir to life as he made preparations for the march on Egypt. The Mamluks, who numbered about 20,000, took steps to defend Egypt against the expected assault. Then fate intervened.

A messenger brought word to Hulegu that the Great Khan, Monge, had died. In keeping with Mongol tradition all the princes, including Hulegu, were summoned to Mongolia to attend a Kuriltai (Council) to elect his successor. Ironically the death of the previous Khan had caused the westernmost armies to pull back after conquering the Poles.

Qutuz also gained an unexpected ally. During his rise to power the sultan had murdered the leader of the Bahri Mamluks, Aqtay, earning the lasting enmity of the faction and its leader, Baibars. Baibars had withdrawn with a group of supporters to Syria from where he had been launching raids on Egypt. Qutuz and Baibars looked on each other with contempt, loathing and distrust. Nevertheless they realized that a Mongol victory would mean their mutual destruction. When Damascus fell, Baibars offered his support, which Qutuz accepted in early March.

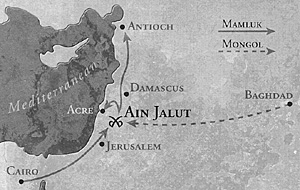

Meanwhile Hulegu pulled his main army back to Maragheh, leaving Kitbuqa in Syria with two tumens or about 15-20,000 Mongols. Kitbuqa was ordered to press on to Egypt. A raiding party was sent into Palestine, cutting the usual Mongol path of pillage and slaughter through Nablus all the way to Gaza, but on Kitbuga's orders, it did not attack the narrow strip of Crusader-held territory along the coast.

The Crusaders, who were too weak to provide any significant resistance against the Mongols on their own, were embroiled in a bitter debate over whether or not to ally themselves with the invaders. Some, like Anno von Sangerhausen, Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, favored a ChristianMongol coalition; others were as vehemently opposed. Kitbuqa hoped his show of charity would sway the argument in favor of the Mongols. He badly misunderstood them.

Two Crusaders leaders, John of Beirut and Julian of Sidon, responded with raids on the new Mongol-held territories. Kitbuqa sent a punitive expedition against Sidon. On entering the town the Mongols plundered the town and massacred its citizens. Only the Castle of the Sea and its garrison held out. Christian ardor for the Mongol cause cooled considerably. It turned frigid when word reached the Crusaders that another Mongol army under Burundai had invaded Poland. Almost simultaneously the French king Louis IX's envoy to the Mongols, William of Rubruck returned from Mongolia with a complete report on the invaders. After reading it Pope Alexander IV sent word throughout Christendom. The Mongols were pagan, brutal savages who were not to be trusted, he declared. Anyone making an alliance with them would be excommunicated. The matter of a Mongol alliance was settled for the Latin Christians.

QUTUZ ADVANCES

When news reached Qutuz of Hulegu's withdrawal, he realized the military landscape had been completely transformed. He ordered a halt to defensive preparations and commanded his men to prepare to advance against the Mongols. In another audacious move he sent envoys to the Crusader leaders in Acre asking for safe passage and the right to purchase supplies.

For the surprised Franks the request presented a thorny question. To cooperate with Qutuz would mark the Crusaders as enemies of the Mongols, opening all their territory to the wrath of the Hordes - the full strength of which they knew they could not resist. On the other hand, Qutuz was the only hope of ridding the region of the foreign invaders. After a lengthy debate the Egyptian request was agreed to.

On July 26, 1260, the Egyptian army began its advance. Near Gaza, Baibars, in command of the vanguard, encountered and destroyed a small Mongol force on longrange patrol. The war had begun.

Kitbuqa, from his base at Baalbek in modern Lebanon, assembled his army and began a march to the south, moving down the eastern side of Lake Tiberias.

Qutuz led his army north and eventually reached the outskirts of Acre. There, while the nervous Crusader leaders watched his army pitch their tents in the shadow of the city, he planned his next move and purchased supplies. Word soon arrived that the Mongols, and a large contingent of native Syrian conscripts, had circled Lake Tiberias and were approaching the Jordan River, following the same invasion route used by Saladin in 1183. Qutuz ordered the army southeast to meet them.

On September 3rd, Kitbuqa turned west across the Jordan and up the rising slope to the Plain of Esdraelon. Meanwhile Qutuz was setting his positions at an apt locale near Nazareth.

Ain Jalut is a fresh-water well meaning the "Spring Of Goliath," since it was believed to be the site of the famous battle between the Jewish shepherd David and the Philistine warrior Goliath -- a story that was as renowned in Islam as in Christianity and Judaism. Because of its location near some of the region's most revered cities (Nazareth, Bethlehem, Jerusalem) and its geographic layout - the vast plain that dominates the region narrows to just five kilometers in width at Ain Jalut, protected on the south by the steep slope of Mount Gilboa and by the hills of Galilee to the north - it saw more than its fair share of combat, including several battles between Arab and Crusader armies during the 11th and 12th centuries.

Qutuz placed units of Mamluk cavalry in the surrounding hills, while ordering Baibars and the vanguard forward.

The Mamluks approached the coming battle with a desperate sense that there was no alternative to victory. One more significant Mongol victory and Islam, as a political power, was finished.

Ghengis Khan's policy of remorseless brutality and no mercy might have been effective in paralyzing lesser men; it had stiffened the resolve of the Mamluks and reinforced their determination. Before the advance, Qutuz, in a speech that brought tears to the eyes of his men, reminded them of the nature of Tatar savagery. There was no alternative to fighting, he said, "except a horrible death for themselves, their wives and their children." It steeled the souls of the Mamluks for the coming battle against an enemy that had never tasted defeat.

THE SPRING OF GOLIATH

THE SPRING OF GOLIATH

Baibars advanced quickly and made contact with Kitbuga's force coming towards Ain Jalut. Seeing Baibars' force, Kitbuqa mistook it for the entire Mamluk army and ordered his men to charge, leading the attack himself. The two armies collided and both seemed to stop in the fierce clash that followed. Then Baibars ordered a retreat. The Mongols rode triumphantly in pursuit, victory in their grasp.

When they reached the springs, Baibars ordered his army to wheel and face the enemy. Only then did the Mongols realize they had been tricked by one of their own favorite tactics: the feigned retreat. As Baibars re-engaged the Mongols, Qutuz ordered the reserve cavalry out from its hiding places in the foothills and slopes and against the Mongol flanks.

Realizing that he was now committed to a battle with the entire Mamluk army, Kit buqa ordered his ranks to charge the Muslim left flank. The Mamluks held, wavered, held again but eventually were turned, cracking under the ferocity of the Mongol assault.

As the Mamluk wing threatened to dissolve and it appeared the entire army might be routed, Qutuz rode to the site of the fiercest fighting and threw his helmet to the ground so the entire army could recognize his face. "0 Muslims" he shouted three times in stentorian tones. His shaken troops rallied and the flank held. As the line solidified, Qutuz led a countercharge sweeping back the Mongol squadrons.

Kitbuqa was now faced with a deteriorating situation. When one subordinate suggested a withdrawal his response was brief: "We must die here and that is the end of it. Long life and happiness to the Khan."

Despite the relentless Mamluk pressure, Kitbuqa continued to rally his men. Then his horse took an arrow and he was thrown to the ground. Captured by nearby Mamluk soldiers he was taken to the Sultan amidst the sounds of battle. "After overthrowing so many dynasties you are caught at last I see," Qutuz exulted.

Kitbuqa, for his part, was still defiant - "If you kill me now, when Hulegu Khan hears of my death, all the country from Azerbaijan to Egypt will be trampled beneath the hoofs of Mongol horses." In a move calculated to insult his captor, Kitbuqa added "All my life I have been a slave of the khan. I am not, like you, a murderer of my master." Qutuz ordered Kitbuqa executed and his head sent to Cairo as proof of the Muslim victory.

With their leader gone, the remaining Mongols fled 12 kilometers to the town of Beisan where they drew up to face the pursuing Mamluk cavalry. The resulting clash broke the remnants of the Mongol force and the few that could escape crossed the Euphrates. Within days the victorious Qutuz re-entered Damascus in triumph, and the Egyptians moved on to liberate Aleppo and the other major cities of Syria.

EPILOGUE

The clash of Mongol and Mamluk at Ain Jalut was one of the most significant battles in world history, yet it is a rare Western history class that even hears mention of it, even though it was as important for Western civilization as those fought at Marathon, Salamis, Lepanto, Chalons and Tours. Had the Mongols succeeded in conquering Egypt, they would have been able to storm across North Africa to the Straits of Gibraltar. Europe would have been clamped in an iron ring all the way from Poland to the Mediterranean. The Mongols would have been able to invade from so many points that it is unlikely that any European army could have been positioned to hold them back.

Instead, the Mamluks stopped the westward Mongol advance and smashed the myth of Mongol invincibility. Qutuz's superior generalship had shown the vaunted Mongols were just as fallible as any army. The psychological impact worked both ways.

The Mongols were shaken. Their belief in themselves was never quite the same and Ain Jalut marked the end of any concerted campaign by the Mongols in the Levant. Except for a few small contingents sent into Syria to conduct revenge raids, the Mongols never attempted a reconquest of the lands that Sultan Qutuz had wrested from them.

The Muslim victory also saved Cairo from the fate of Baghdad; destroyed the last hope of a Christian restoration in the Middle East; doomed the remaining Crusader states; and raised Mamluk Egypt to the status of leading Muslim power and the home of what was left of Arabic culture and learning.

For Qutuz, the ecstasy of victory was relatively short lived. After Aleppo was retaken, Baibars suggested that he be given the emirate of the region as recognition of his contributions. Qutuz refused. Baibars sulked.

When the Mamluk army was only a few days from its triumphal return to Cairo, Baibars went to see Qutuz on a matter of state. Reaching out in greeting he grabbed the Sultan's sword hand and drew a dagger from his belt then drove it into Qutuz' heart. When the army entered Cairo, Baibars rode at their head as Sultan - destined to be the greatest of all Mamluk warriors. But that is another story.

Mamluk and Mongol

- Battle of Ain Jalut 1260

The Sack of Baghdad 1258

2003: The New Hulegu (Saddam Hussein Speech)

The Mamluks: Army, Organization, and Tactics

The Mongols: Army, Organization, and Tactics

War and Ramadan: Myth and Reality

Chronology of Events

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 3

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.