St. Clair had served as a general during the Revolutionary War and lived in Ligonier, Pennsylvania, where nearby almost 40 years earlier General Braddock's force was nearly wiped out at the beginning of the French and Indian War. As soon as he arrived at Fort Harmar things began to go wrong. Earlier an advance party of US Army soldiers and workers went upriver along the Muskinghum to prepare a meeting site to arrange a comprehensive treaty with representatives of all of the Indian nations. The group completed their task without incident, but was later attacked by a Mingo raiding party that killed several soldiers and forced the evacuation of the just-completed conference site. Learning of the raid after his arduous journey, and suffering from gout, the governor flew into a rage.

He issued a proclamation casting blame on all of the Ohio Indians and wrote back to the President that this attack exemplified their duplicity, and a reason so many distrusted any attempt at a peaceful settlement. St. Clair's eagerness to scuttle the talks quickly confirmed the correctness of chiefs Black Hoof and Little Turtle, leaders of the two largest nations of the Ohio Territory, in boycotting the treaty conference. St. Clair's outburst and subsequent actions served to drive even more of the area's natives to side with the hard-line Shawnee and Miami nations.

The treaty President Washington desired, and St. Clair was charged with negotiating, was going to be hard to secure even before the governor's arrival and ill-tempered remarks. Earlier "treaties" at Fort McIntosh (January 21, 1785) and at the mouth of the Great Miami River (February 1,, 1785) were achieved more through intimidation and the plying of alcohol than through a process of negotiation and compromise. Indian raids and punitive excursions by settlers' militias, including one in 1786 led by war hero George Rogers Clark that ended in atrocity, embarrassment and defeat, formed a backdrop of mistrust and growing animosity. The escalating violence and demands by settlers to do something to bring order along the frontier seemed to many in government a path from which there was no good way out. In a letter to Patrick Henry, George Rogers Clark wrote in 1787, "I don't think that this country, in its infant state, has so gloomy an aspect as it does at present." [5]

Besides the Americans and Indians, the British were also becoming increasingly alarmed with events occurring south of Lake Erie. The new governor of Canada, Sir Guy Carleton (Lord Dorchester), was concerned the growing US presence in the region could become a threat to the Crown's remaining North American colony, and the start of another costly war. He was also worried about how the threats posed by the settlers and US forces were leading to increasingly strident demands by the natives for British protection, food and weaponry. His man on the spot, Colonel Alexander McKee, warned the credibility of the British government and Crown was at stake. Failure to meet the needs of their Algonquin subjects in Ohio could lead to an outbreak of violence that would spread north into Canada, and the possible loss of British control in the entire region.

Trying to determine the exact cause or event that led to outright war between the United States and the Native Americans of Ohio is akin to identifying the drop of water that presaged a flood. The failure of the treaty St. Clair eventually had signed at Fort Harmar by those who did attend on January 11, 1789 was certainly a reason why President Washington eventually saw no alternative to war by 1790 in order to restore order and provide for the settlement of the region. Atrocities and raids were occurring with increased frequency and ferocity as one season led to another.

The banks of the Ohio River were scenes of particularly gruesome and pitiable episodes. Flatboats full of settlers were particularly vulnerable, whose occupants were often lured close ashore by cries for help by previously taken hostages or light-skinned decoys. The bodies of slain settlers, slaughtered animals, and the pathetic flotsam of lost personal items and wreckage floated downriver in everincreasing amounts past horrified settlers in Kentucky or the Symmes tract (soon to be named Cincinnati). Those who were not killed faced being sold into slavery to other Indian tribes, or death by torture. The tales told by those who escaped or were rescued spurred others to flee or form reprisal parties to exact vengeance. With little to no regard for determining the innocent from those who were culpable on either side, the deadly cycle of violence escalated rapidly.

HARMAR'S EXPEDITION

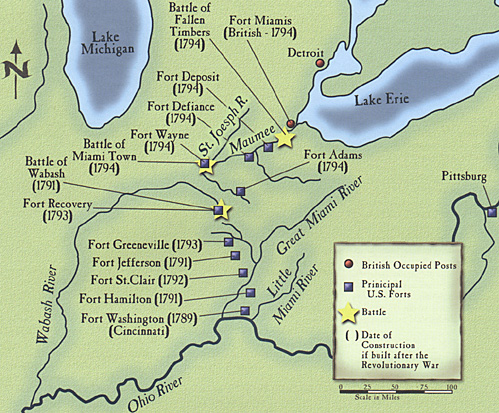

On June 7, 1790 Secretary of War Henry Knox authorized General Josiah Harmar to lead a punitive expedition against the Miami and their Shawnee allies. It was hoped that a determinedshow of force, and the destruction of Little Turtle's home at Kekionga, would compel the Indian's acquiescence to US control and their acceptance of the terms laid down in the Fort Harmar treaty. Not wanting to alarm the British, Knox also informed the British of the purposes and timing of Harmar's expedition, who promptly passed the information on to the Miami and Shawnee.

The lack of surprise and the time it took to assemble, train and equip the 320 US regular army soldiers and 1,200 militia handicapped the mission even before it set out at the beginning of October. The US force proceeded north from Cincinnati to the Maumee River. Though successful in destroying some villages, it was unable to bring the main body of warriors to battle. Harmar then divided his force as they approached Kekionga in order to trap the elusive foe. Instead, his separated wings became strung"out and lost touch with one another as the weather worsened. On October 19th

Little Turtle's 700 warriors struck. Most of the militia quickly ran from the fight. This left the regulars to fight a series of battles that resulted in 120 of their number dead or captured (who would soon be dead as well). Despite an attempt at a counterattack the next day, Harmar was forced to order a retreat that didn't end until the survivors straggled back into Cincinnati in November.

ST. CLAIR TAKES' THE FIELD The news of General Harmar's defeat shocked the Governor and terrified settlers across the territory. The follow-up Indian raids that occurred across the frontier and along the Ohio River that winter of 1790-91 were among the worst anyone could recall. Both the President and Congress became aware that the situation' in Ohio was now a crisis. In March 1791 legislation was passed authorizing Governor St. Clair to call out militias from bordering states to put down the rebellion, and for funding to raise the US Army to a force of over two thousand.

St. Clair decided to lead the campaign himself. The need to find blame, as well as

charges of intoxication (a popular charge against US military leaders who fail), made General Harmar's continued service impossible. The Governor's task was a daunting one. Most of the US Army regulars who survived had expiring enlistments or were sorely needed to garrison the forts already constructed. Many of those who were sent as part of the militia call-ups arrived untrained, unarmed, and in some cases unwilling to go to war. When St. Clair finally set out on August 7`h he had a little more than 2,200 men under arms, of which 718 were US Army regulars, instead of the 4,000 he had hoped for in the spring. After Congress authorized his appointment, St. Clair met with the President to discuss the upcoming campaign. The President concluded the meeting with the words "General, beware of surprise!" [6]

St. Clair's campaign began well enough. Earlier in June two raids were launched, one with 750 mounted militia under Kentucky Brigadier General Charles Scott and another, smaller force led by Lt. Colonel James Wilkinson and Colonel John Hardin. Both raids destroyed several Indian villages and caused several groups to flee the region entirely. St. Clair's force was not as hard-hitting, however. Stricken with gout, the General could often only be moved in a litter, and even then many times in excruciating pain. At one point the army only managed to make 22 miles in five days of travel.

Worries about his supply line also aggravated St. Clair, prompting him to stay for days at forts and portages to await the arrival of supply trains,' or td leave portions of his force behind as garrisons. Further trouble arose when it was discovered that due to graft and corruption, critical items such as uniforms, tents, and ammunition were found defective or in short supply. The quartermaster of the army's horses proved incompetent, not even knowing how to feed or corral the animals, with the result that after one month almost half of these animals were dead, stolen, or lost.

Aware that November 3rd brought the expiration of most of his militia's term of service, St. Clair pressed on from Fort Jefferson on Octobef 24th despite the increasingly foul weather and his inability to catch the elusive enemy force of warriors, estimated to be over 2,000 strong. On November 1st, St. Clair paused along the Wabash River on a low ridge to allow a supply train to catch up. He dispatched his most veteran unit, the 1st US Infantry Regiment, to escort the supply train during the last leg of its journey. Having been in cold rain mixed with snow for nearly a week, the remaining 1,200 exhausted soldiers hurriedly pitched tents, built fires, and began cooking their food. No pickets were posted or defensive works built up. Thinking he was over fifteen miles from Kekionga and in a secure position surrounded by swamps, St. Clair felt confident that victory was close at hand.

Unknown to the US force, they were just a little more than a mile away from the main body of Little Turtle's and Blue Jacket's force of 1,400 warriors who were mostly Shawnee and Miami, but warriors from several other' nations including the Wyandot, Iroquois, Cherokee, Ottawa, and Delaware were also present.

Shortly after the camp stirred to life in the morning of the 4' the Indians struck. As before, the militia, particularly those from Kentucky, were the first to bear the brunt of the initial onslaught and the first to break. St. Clair, despite being in tremendous pain and having his horse shot out from under him, hobbled from one group to another as the U.S. forces fought the war-painted and screaming enemy. Most of the fighting was at close quarters, but Indian marksmen were particularly good at picking out officers or anyone else who showed initiative and the ability to rally their fellow comrades.

The crews of the artillery pieces panicked, sending the few rounds they got off high into the trees before they were tomahawked down. By the end of the day St. Clair found his force being pinned against the Wabash into an increasingly. smaller area, turning his command into a huge target the Indians couldn't miss. A counterattack led by St. Clair and Lt. Col. William Darke was anticipated, and shot to pieces from fire on three sides, with the loss of one of Darke's sons, Joseph, a captain. As the evening approached the battle turned into a massacre. Some warriors boldly strode up to Shamanese frozen in terror to count coup before shooting them down at point-blank range. Taking scalps and mutilating the dead distracted an increasing number of warriors, allowing some survivors to slip away, but the carnage for St. Clair's force was terrible. Knowing that surrender was not an alternative, St. Clair gave orders to abandon any wounded and make a breakout for Fort Jefferson. Colonel Hamtramck and the 2nd U.S. Regulars managed to fight their way out, as did the group with St. Clair, who rode out on one of the few remaining packhorses.

Over 900 of St. Clair's force were killed or wounded, nearly three-quarters of the force that fought in the battle. Fewer than 500 of St. Clair's entire command eventually returned who set out from Cincinnati. Not until World War II, with the surrender and defeat of the army defending Bataan, would there be a comparable defeat by an enemy of a US Army in battle.

Among those left behind was General Richard Butler, who led raids against the Indians for almost 10 years. Suffering a slow death by torture, his horribly mutilated body was found the next year. Word of the defeat shocked President Washington. First learning of the disaster during a dinner entertaining guests, the President exploded with rage after they left. Venting to his aide, Tobias Lear, the President singled out St. Clair for blame. He proclaimed "The blood of the slain is upon him, the curse of the widow and orphans, the curse of heaven!"

[7]

A Dark and Bloody Ground The Ohio Campaign 1790-1795

Introduction

War in Ohio

Wayne Takes Command

Dramatis Personae

US and Indian Forces

Map of Battle of Fallen Timbers (very slow: 209K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 3

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds

direct from LPS.