Introduction

Introduction

It is said that to the soldiers who become casualties, the size or historical significance of a battle is irrelevant. However if it means anything to their ghosts, the official description of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) action at Elouges on August 24, 1914 was an insult, for most simply describe it as "The flank action at Elouges". It was, however, a full-blown battle, the importance of which was not understood at the time.

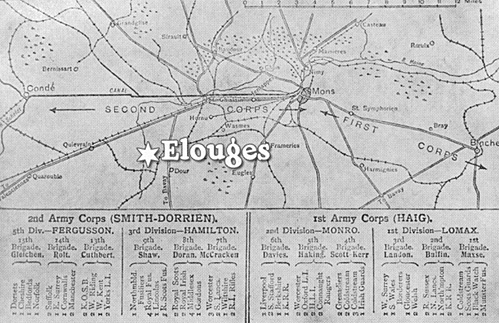

Having failed to stop the advancing Germans the previous day, in a battle now known as 'Mons', Sir John French ordered his army to fall back to a new defensive line. Throughout the long night troops had tramped back toward le Cateau covered by divisions acting as rearguard. By the morning of the 24th, it seemed they had broken contact and the rearguard elements also prepared to move off.

An Avro scout aircraft flown by Captain Shephard had been over the right flank of the German advance since dawn. Shephard and his observer Lieutenant Benham-Carter found themselves flying low over a huge advancing horde, a force so large the amazed Shephard could only estimate the size by describing the amount of area it took up.

Von Mucks' First Army was moving to envelop the British left. Massive columns of troops were deployed in four attack groups on a five-mile wide front and their artillery was digging in along the Mons-Valenciennes railway. So much artillery was digging in, that it was obvious the Germans were preparing a major assault in the direction of Bavai. Shephard estimated the enemy as five miles wide and five miles deep. Behind this force, already enormous compared to that which it was about to attack, yet more columns of German troops stretched off for twenty miles and were advancing on a front ten miles wide. It could be no less than an entire Army comprised of two or more corps.

The Avro's crew had found on return to their base that the flying element had retreated in compliance with orders of the day. The pair set off to search for them. This was not as simple as it seems, for at this early period of WW1 the aircraft lacked recognition markings and ground troops tended to shoot at any aeroplane in the presumption it was an enemy. Eventually, despite occasional ground fire and cluttered roads, Shephard spotted a large red pantechnicon he knew as belonging to his squadron and landed in a field near the road along which they were retreating. Although on the move to LeCateau to set up a new flying field, his commander saw the importance of the information and rushed it to the nearest HQ. Fortunately, this was that of the 5" Division, for whom the reconnaissance mission had been flown.

Sir Charles Fergusson, commanding general (GOC) of the British 5th Division, did not receive the information until 10am. Having consulted his maps, he realized that an extremely dangerous situation was developing. His division was part of II Corps and had been ordered to cover the left of the BEF, which was now commencing a general retreat after the battles of the previous day around Mons. He had expected to do this on the move, his various elements falling back in succession until he arrived at Bavai. Apart from a small reserve, most elements of Fergusson's own division were already on the road and well beyond recall. Although the 13th and 14th Brigades did not move off until 11:30 am, there was neither time to get off orders to stop them, nor seek higher approval for the division to change its ordered march in compliance with II Corps dispositions.

The 2nd Cavalry Brigade, previously working with him, had been already sent off to the rear to establish a new position. Fortunately, they had not got far and the urgent dispatch of couriers brought them hurrying back with the full approval of General "Bull" Allenby, their divisional commander. Along with the Cavalry, the only force he could use to slow the German columns would be his rearguard reserve of the 15th Brigade. However, this was at half strength, two battalions being engaged in duty else where and not available.

Thus, his emergency force comprised only these two battalions, one each of the Norfolk and Cheshire regiments. They were supported by a single battery of guns; 119 Royal Field Artillery (RFA) whose six 18pdrs were equipped entirely with shrapnel. The Cavalry were bringing their own guns, but their 13pdrs were also armed only with shrapnel.

The cavalry, infantry and guns were rushed to an area between Elouges and Audregnies, identified by Shephard as the line of German advance. If disaster were to be prevented, the advancing enemy would have to be delayed for at least a day.

GHQ of the BEF was still at Bavai, only five miles to the rear of Elouges. Large numbers of troops were passing through there and Fergusson suspected that the retreat down the limited roads available would be creating chaos. He reasoned they would need time and he was right. Bavai was jammed with refugees and retreating troops. Carts, vans, motorcars, foot traffic and marching men were clogging the town. If the German force sighted by Shephard was able to reach Bavai by afternoon a disaster would result. The situation was so grave that had the Germans reached Bavai, it is likely that the BEF would have had their retreat blocked, and the only army the British had available in 1914 would have been taken prisoner.

Sir John French, GOC of the BEF was on his way from LeCateau to Bavai. He arrived there while fighting was still taking place at Elouges and reported in his memoirs that

"The whole country-side showed those concrete evidences of disturbance and alarm which brought home to our minds what this retreat meant and all that it might come to mean."

Hs memoirs continued with a description of Bavai at 2:30 in the afternoon.

"It was with great difficulty that my motor could wind its way through the mass of carts, horses, fugitives and military baggage trains which literally covered almost every yard of space in this small town. The temporary advanced HQs were established in the market place, the appearance of which defies description. The Babel of voices, the crying of women and children, mingled with the roar of the guns and not far distant crack of rifles and machineguns, made a deafening noise amidst which it was most difficult to keep a clear eye and tight grip on the rapidly changing course of events."

The firing described by Sir John French was of course from the fighting then raging at Elouges only a few miles away. The task facing the troops under the command of Fergusson was therefore not only vital, but of such significance that to lose control would result in disaster for the British Army.

The Battlefield

The area between Elouges and Audregnies sloped upward gently from the main Mons - Valenciennes railway and highway. The ground resembled the glacis of a fort and provided little cover for an attacker wanting to move up hill, as the Germans planned. It was good defensive ground for riflemen supported by machineguns and shrapnel-firing artillery. It was ground that would be far too open for an attacker to do anything but absorb casualties and press on. A few sunken tracks crossed the face of the slope, providing some cover for the defenders as time prevented them digging trenches. A sunken road between Audregnies and Elouges provided some emergency cover right at the top of the slope, but this was at best a final fall back position. Being late summer, the corn crops normally covering the slope had been harvested and the low stubble would provide no cover for an attacker.

The area between Elouges and Audregnies sloped upward gently from the main Mons - Valenciennes railway and highway. The ground resembled the glacis of a fort and provided little cover for an attacker wanting to move up hill, as the Germans planned. It was good defensive ground for riflemen supported by machineguns and shrapnel-firing artillery. It was ground that would be far too open for an attacker to do anything but absorb casualties and press on. A few sunken tracks crossed the face of the slope, providing some cover for the defenders as time prevented them digging trenches. A sunken road between Audregnies and Elouges provided some emergency cover right at the top of the slope, but this was at best a final fall back position. Being late summer, the corn crops normally covering the slope had been harvested and the low stubble would provide no cover for an attacker.

Laterally however the ground was cut by allotment fences and tracks, which made movement from side to side of the field difficult. This would prove particularly significant for the cavalry for whom any sort of fence was a serious obstacle. Worse, the fences were mostly of barbed wire. Despite the image one might have of European countryside, this area was no longer pretty.

Many factories and industrial plants were present and coal mining was the main industry. The battlefield was part of an area known as `The Black Country" and although crops were still grown they were interspersed with slagheaps, rubbish and all the trappings of modern industrial waste. So much coal dust lay on the ground that bursting shells raised great clouds of it and restricted visibility. On a very hot summer day such as this, the smell of cut corn crops from the fields mingled with coal and industrial odors.

The presence of slagheaps, cottages, garden allotments, washing hanging on clothes lines, trolley tracks to the factories, etc. all presented difficulties both for maneuver and the sighting of the direct fire field artillery both sides mostly had available.

Battle of Elouges August 24th 1914

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 2

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.