General officers might be Field Marshals, Generals,

Lieutenant Generals, or Major-Generals in descending order

of precedence.

General officers might be Field Marshals, Generals,

Lieutenant Generals, or Major-Generals in descending order

of precedence.

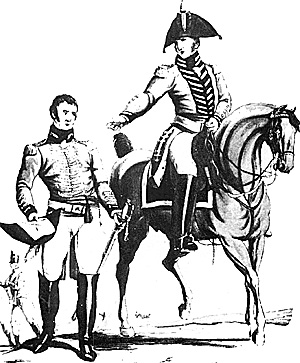

At right, British staff officers (1814 Hamilton Smith series)[National Army Museum]

The junior rank of Brigadier General was also conferred from time to time, but like its naval equivalent of Commodore, this was invariably a local promotion and usually quite transient. No particular duties attached to any of them; a Lieutenant General might command a division or its equivalent, while a Major General might have a brigade, but this was a very shaky rule of thumb and there was in fact no requirement for a general officer to be employed at all.

Staff officers proper fell into three sometimes overlapping categories. These comprised the Quartermaster General's Department, the Adjutant General's Department, and Personal Staff Officers. Some posts had originally been purchasable, but this was entirely squeezed out during the 1790s and instead almost all posts were filled by selection - or rather by patronage since in practice there was no objective assessment system.

There were in fact very few qualifications demanded of staff officers. The few graduates of the Royal Military College were routinely commissioned into the Royal Staff Corps, a quasi- Engineer unit coming under the authority of the Quartermaster General, but otherwise almost anyone could be appointed to the staff providing hehad served at least one year as a regimental officer.

Broadly speaking the Quartermaster General's Department quite literally dealt with the quartering and transporting of the army and everything associated with it. This included the reconnoitring and sometimes the improvement - through the medium of the Royal Staff Corps - of the routes along which the army was to march. Inevitably these duties involved an element of intelligence gathering, which properly speaking fell to the Adjutant General's Department along with the interrogation of prisoners.

However the department was not responsible for supplies, which were actually procured and transported by the civilian Commissariat. The Adjutant General and his assistants were responsible for more routine administrative matters, such as discipline and military administration.

Both departments were similarly organised on a surprisingly ad hoc basis. Each 'command', be it a field army or a military district had its own staff comprising an Adjutant General (AG) and Quartermaster General (QMG) and one or two Assistants (AAGs and AQMGs) normally ranking as Lieutenant Colonels or Majors.

Below them came an indeterminate number of Deputy Assistant Adjutant Generals and Deputy Assistant Quartermaster Generals (DAAGs and DAQMGs) who were usually Captains or sometimes Subalterns.

So-called 'personal' staff officers comprised Brigade

Majors and Aid de Camps (ADCs). Although recommended by

their Generals, the first were in effect Brigade Adjutants and their

appointments often outlived their patrons. On the other hand

ADCs appointments were very much in the gift of their masters. A

General was entitled to have three at public expense, a Lieutenant

General two, and a Major General one. If this allocation was found

to be insufficient to fulfill the duties demanded of them, others,

distinguished as 'Extra' ADCs could be added to a General's

personal staff at his own expense. Regulations required all officers

appointed to staff positions to relinquish their regimental rank and

retire on to the Half Pay [5]

which is why so many nominally belonged to exotic or long

disbanded corps such as the Ceylon Regiment or the Royal

Glasgow Regiment to name but two examples.

The reason was of course that if an officer was to be

absent from his corps for any length of time it was desirable for the

resulting vacancy to be filled. In practice observance of this rule

often depended on circumstances. The appointment might only be

of short duration and if both staff officer and regiment were serving

in the same theatre it was understood that he might retain his Full

Pay commission on the understanding that he could be recalled to

regimental duty if the circumstances demanded.

[1] Callahan, R.

The East India Company and Army Reform 1783-1798 Harvard

1972

More Officers and Gentlemen Part I

Officers and Gentlemen Part II

FOOTNOTES

[2] Dates of this and

other establishment alterations are taken from Collection of

Regulations (1807)

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Hence the

importance of the various allowances paid to Staff officers for

horses and accommodation. Personal staff officers would also eat at

their General's table.

Part I: Introduction

Part I: Regimental Officer Structure

Part I: Surgeon, Chaplain

Part I: Quartermaster, Paymaster, Adjutant, Agent

Part I: Staff Officers

Back to Age of Napoleon 30 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com