At dawn on the (lay of the battle (27th) the weather was

misty but as soon as it was light enough Reynier launched his attack.

His objective was the only possible one, the dip in the Serra crossed by

the San Antonio de Cantaro/Palheiros road, this being the lowest

point in the Serra. The troops started off in regular forination, but due

to the unevenness of the ground they quickly became less organised. It

must have seemed to the British that the attack was being delivered by

a number of small groups, moving diagonally up the slope.

At dawn on the (lay of the battle (27th) the weather was

misty but as soon as it was light enough Reynier launched his attack.

His objective was the only possible one, the dip in the Serra crossed by

the San Antonio de Cantaro/Palheiros road, this being the lowest

point in the Serra. The troops started off in regular forination, but due

to the unevenness of the ground they quickly became less organised. It

must have seemed to the British that the attack was being delivered by

a number of small groups, moving diagonally up the slope.

Merle's division began moving up the steep slope some three quarters of a mile to the right of the San Antonio de Cantaro road. Its skirmishers came into contact with the light companies of the 7th, 88th and 45th Allied regiments, strung out along the front and they soon began to push the British line up the hill. The French regiments veered to their left thereby passing across the front of the 88th, directing their advance towards the unoccupied part of the crest between them, and the British troops placed immediately above the pass. The skirmishers left behind the eleven battalions forming this storming column.

Although the mist was dense, Picton, hearing the shooting, detached a wing of the 45th under Major Gwynne and two battalions of the 8th Portuguese to fill the unoccupied space. Because of the mist, he under-estimated the strength of the column. He also had to cope with Heudelet's vanguard along the high road where a column of four battalions, the 31st Uger, was pushing up the road, driving in Champlemond's skirmishers. As the mist began to lift, von Arentsebildt's guns opened up on the French, halting their advance.

The 31st Leger tried to hold its ground, aiming gallantly trying to right itself in the chaos, but they were swept even further to the right by the fire of the Anglo-Portuguese guns. Picton, whose area it was, sensing danger, left command of this sector to Mackinnon, and moved to his left where the firing was becoming heavier, emanating from a column of Merle's division who, once the mist had cleared, could be seen climbing the slope. Merle's people made good, albeit slow progress due, to the problems of the rocky, heather-covered, steep terrain.

They reached the crest before any British troops were there to meet them.

Wallace, a colonel in the 88th, one of Wellington's best, threw out three companies as skirmishers to cover his flanks. He ordered the wing of the 45th to fall in on his right and charged the disordered French mass diagonally across the plateau. At the same moment, the 8th Portuguese, further along the hilltop, opened a rolling fire against the enemy's front.

Meanwhile, Wellington, who had used the convent as an observation post, came up with two of Thompson's guns which fired upon the French flank and at the rear of a mass of soldiers who were still clambering up the hillside. At the same time, the light companies of the 45th and 88th, who had been driven to their right, were rallied by Picton in person and brought up to the plateau on the right of the Portuguese. They halted 60 yards from the leading French flank, opening up a rolling fire upon it. The four British battalions were facing eleven French ones.

But Wallace, was quick to see an advantage: the French were exhausted from their climb and in chaos, so he ordered the 88th to charge them before they had time to recover their breath.. His timing was flawless. The French were slow to appreciate the situation and had not recovered their wits enough to realise that they greatly outnumbered the defenders. Four of their battalions were sent rolling down the hill by Wallace's brave band. The firing was followed by a bayonet charge. As some of the French were descending, they collided with the 2nd Leger who had almost reached the skyline but who were struggling among the rocks which crowned the crest. Grattan describes the situation atmospherically

All was confusion and uproar, smoke, fire and bullets, French

officers, soldiers, drummers and drums, knocked down in every

direction; British, French and Portuguese mixed together, while in the

midst of it all was to he seen Wallace, fighting like his ancestor of old

and still calling to his soldiers to "press forward". He never slackened

his fire while a Frenchman was within his reach, and followed them

down the edge of the hill, where he formed his men in line, waiting for

any order that he might receive, or any fresh body that might attack him.

[11]

Picton was rightly, but uncharacteristically, fulsome in his tribute to this action.

He wrote to Wellington that:

The Colonel of the 88th and Major Gwynne of the 45th are entitled to the whole of the

credit and I can claim no credit whatever in the executive part of that brilliant exploit

which your Lordship has so rightly and so justly extolled. [12]

The British troops followed the retreating enemy down the hillside until they came

under fire from Reynier's artillery when they wer ordered back to their original positions.

The French were rattled. Reynier, seeing his right column

rolling down the slope and the disintegration of the 31st under heavy

Anglo-Portuguese fire ordered Foy's brigade to move up the hill to the

right of the 31st. Foy assumed that this order was only to be

implemented when it became clear that the first party's climb up the

slopes had succeeded. Not so! Reynier cantered up to Foy, shouting :

Why don't you start on the climb? You could get the troops

forward if you chose to do so, but don't choose to do so. [13]

So ordered, Foy and his brigade proceeded to climb the

heights. He could see Merle's division retreating in disorder, pursued by

Wallace. Foy's objective was the lowest hilltop to the right of the San

Antonio pass. Eventually, the French faced Picton's division who

were soon joined by the 9th Portuguese from Champlemond's brigade,

with an unattached battalion of the Thomar Militia. This numerically

inferior force was also joined by some of Leith's men. Despite

Reynier's numerical superiority, he kept no reserves or flanking

division to the south of the high road, so it was possible for Picton's

hard-pressed troops to be reinforced almost immediately.

While the fog continued to hover over the crests, Leith

ordered his brigades to the left while Hill detached some of his troops

to occupy the heights from whence the 5th Division were being

evacuated. By the time Foy had begun his attack, Leith had just

reached the San Antonio pass, accompanied by Spry's Portuguese

battalion, heading his column, followed by two battalions from the

Lusitanian Legion, and Barnes's British Brigade. All these were

accompanied by one of Dickson's batteries. He left his guns to Von

Arenschildt, whose ammunition was running low and whose fire was

beginning to slacken. Picton considered that he.was now strong

enough to cope with the activity at the pass and suggested that he

would be obliged if Leith would deal with the attack which was being

made on the height on his immediate left. But Foy was now becoming

dangerous. He managed to force his way to the summit despite the

destructive fire, which eventually managed to drive them back: but

despite this, the Thomar militia fled down the declivity and the 8th

Portuguese fell back in disorder. Leith appeared in the nick of time

with Barnes's three battalions, who came up the communication road

behind the plateau. Leith described it thus:

A heavy fire of musketry was being kept up upon the

heights, the smoke of which prevented a clear view of the state of

things. But when the rock forming the high part of the Serra became

visible, the enemy appeared to be in full possession of it. A continued

fire was being kept up from thence, and along the whole face of the

Serra. [14]

Leith realised that time was more or less on his side as only

the head of the French column had in fact reached the top. He

deployed his leading battalion across the summit, while sending the

38th to go between the enemy and the reverse slope of the position.

This move was none too successful, but Leith handled the 9th

diagonally across the plateau to place it alongside the leading flanks

of Foy's battalions. The 9th opened with a volley at 100 yards and

then advanced, firing, in the face of very little return from the enemy

who appeared disconcerted by the appearance of a new force parallel

with its flank. At 20 yards from the enemy the 9th lowered its

bayonets, preparing to charge; Leith riding in the van, waving his

plumed hat. The enemy gave way.

Foy described the movement thus

My heroic column, much diminished during the ascent, soon

reached the summit of the plateau, which was covered with hostile

troops. Those on our left made a flanking movement and smashed up

by their battalion volleys; meanwhile, those on our front, covered by

some rocks, were murdering us with impunity. The head of the column

fell back, despite my efforts. I could not get them to redeploy;

disorder set in and the 17th and 20th raced downhill in headlong

flight. [15]

Reynier had only one regiment in reserve after this, the 47th

Line. He had completely lost two regiments, 2,000 men and more

than half their officers. Picton's division had 427 killed and wounded

and Leith's 160. Two senior officers had been hit - one of which was

the Portuguese Brigadier Champlemond, and two majors, one from the

45th and one from the 88th. Because Wellington had a good

communication road to his rear, he had great flexibility in moving

troops from one section of the theatre to another. And the Allied

troops had yet another time advantage which they exploited to

perfection - that needed for the French to recover breath from the

climb.

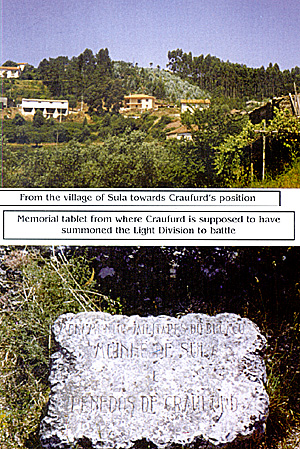

Loison started just before Marchand with Simon's six

battalions on the right, and Ferey's six on the left. Each group was

preceded by skirmishers. During the easy stage of their climb they met

the whole of Pack's 4th Cacadores on the hillside in front of his line

battalions. Craufurd, commanding the Light Division, had

thrown the 95th (700+ rifles) and the 3rd Cacadorcs (600 rifles)

into enclosures in front of Sula. All that Loison could see was the 1st Division,

far above him on the left on the highest plateau, with Cole further

away in the direction of Paradas. Loison managed to evict the

Cacadores and the Rifles from the lower slopes and then from

the village of Sula.

The French then came up against heavy

artillery fire from Ross's guns, trained on the exits from Sula,

while Cleeves's German battery joined in from the head of the

ravine, taking Ferey in the flank. Sula was an impossible place

to stop, so Loison's people pressed forXvard using Ross's guns

as their objective. Because the slope was much steeper nearer

the top, the British and Portuguese rallied above Sula. The

French managed to progress without problem up the easy

slope. There being no track, Ferey's people drifted chaotical-

ly to their left, close to the edge of the ravine which formed the

boundary of Craufurd's position.

Lying in the hollow road which ran parallel to the head of

the ravine, Craufurd had the 43rd on the left and the 52nd on

the right, carrying a total of 1750 bayonets. He had had dur-

ing this time been standing by the windmill (still there today,

known as Craufurd's mill).

The French stood shocked. Then three companies of the

52nd were directed to deal with Simon's right flank while Lloyd and the 43rd

did the same to the left. It was an impossible situation for the French who

broke their columns and went hurtling down the hill. Some poor wretches lost

their footing in the midst of this carnage, and rolled down to the bottom of the

ravine. The Light Division pursued the seething mass as far as Sula when they

came within range of the French guns. But one French battalion on Ferey's

extreme left remained which was despatched by Coleman's Portuguese Brigade

resulting in it too joining their defeated colleagues.

What was left of Loison's brigades reeled back to their original position

under cover of one of Mermet's regiment which had been held in reserve. Some

skirmishers bickered with Cranford's outposts so Wellington relieved the very

tired members of the Light Division with Lowe's German Brigade and

Campbell's 6th Cacadores. A few French managed to get into Sula but they were

soon evicted by the 43rd.

Losses were as follows in this action were as follows: Loison lost 1200

men, his senior brigadier, Simon being wounded in the face and captured by an

English private. [16]

The Cacadores and 95th had 119 casualties and the 43rd and 52nd had only

three men killed, with two officers and 18 men wounded. McBean's Portuguese

battalion lost one officer and 25 men. In total Loison's attack was repelled

with the English loss of only 200 men.

These are the two main engagements of the Battle of Bussaco. In terms of

casualties, a victory it certainly was. But most historians regarded it as a

holding operation for the Allies en route for Torres Vedras.

[17]

The day after the battle (on the 28th September) Montbrun's cavalry

produced a good piece of reconnaissance. They discovered the Boialvo road

(which did not exist on the Lopez maps) enabling the French to outflank the

Allied armies. In a dispatch to the Emperor, however, which got captured by

Wellington's men never seen by the Emperor, Massena dressed up the number

of casualties describing them as negligible, and the operation as a victory

because, he argued, having discovered the Boialvo road, he had managed to

outflank the Allied armies. Although Napoleon received very few dispatches

during the invasion of Portugal, he managed, through the indiscretions of

British officers, to get a good deal of information about the progress of the

campaign from English newspapers. He later told General Foy that he regarded

the Bussaco operation as a failure.

Wellington was extremely annoyed about having been outflanked.

Professor Horward blames him for incompetence, but it is clear from studying

Professor Oman that the situation was as follows: Wellington knew of the

existence of this road and had detailed Trant and his Portuguese militia to

control this road. Trant did not arrive at the Boialvo road until

the 28th September because his senior (Portuguese) officer had

ordered him to take a circuitous route to Bussaco to avoid the French.

Reasons for the Reverse

There were many reasons for the French reverse at Bussaco.

Massena made an initial error of judgment in the choice of route to

Bussaeo for most of his party giving Wellington a time advantage. To

be fair to Massena, the reason for this decision was the lack of

knowledge of the terrain: the absence of guides, bad maps and 30

Portuguese non-French speaking collaborators. History has shown that

he was unwise to ignore the advice of the majority of his senior

commanders not to attack the allies in such a strong position. He used

the Emperor's orders to take the course of action that he did to cover

his real motive for attacking the heights, to assert his authority over

his dissident colleagues.

Koch tells us that, due to the difficulties of the terrain, he

was unable to find a satisfactory location for an observation post

from where he could see the battlefield as a whole. Thus he had only

reports from his officers as to how the battle was progressing on

which to base his orders.

If Marbot is to be believed, to bring Mine Leberton with him

meant that he had to set up his headquarters at Mortagoa to keep her

safe and sound which meant that contact with his senior officers and

troops was minimal; [18] Last but not least, Bussaco was the first experience he had of fighting against 'les anglais'. He greatly under-estimated their competence as he had not engaged them in an important battle previous to this point in the campaign. He also under-estimated the competence of the re-formed Portuguese army, disbanded by Junot at an earlier stage, but since trained and officered by Beresford and English officers.

The official French line, as seen through the columns of

"Moniteur" the official French government newspaper, for public

consumption, was that the battle was merely a skirmish, an Outpost affair.

The private view of many French officers was expressed by

Colonel Noel. Not wishing to seem disloyal even some time after the battle, he wrote:

Only bold Massena and the enthusiastic French soldiery

would have dared to undertake such an attack [19]

But shortly after that, he writes bitterly -

After the defeat of the 27th we did what we should have done

at the beginning of this battle, that is to say we did a proper

reconnaissance of the locality. Had this been done earlier, we would

have discovered a road that woul have enabled us to turn the enemy's

position. Our Portuguese officers appeared not to know of its

existence: the countryside being deserted, there were no locals to put

us in the picture, it took a belated exercise by our cavalry to discover

it. How much unnecessary blood was spilt as a result of this omission. [20]

General Marbot, one of Massena's ADC's says much the same in his memoirs.

Wellington's View

In Wellington's view, the benefits of the Battle of

Bussaco were:

The battle has had the best effects in inspiring

confidence in the Portuguese troops both among our croaking

officers, and the people of our country. It has likewise removed

an impression which began to be very general, that we intended

to fight no more but to retire to our ships; and it has given the

Portuguese troops a taste for an amusement which they were

not before accustomed, and which they would not have acquired

had I not put them in a very strong position. [21]

Massena learned at least one lesson from Bussaco

which stood him in good stead at Torres Vedras, and that was

not to attack an enemy placed in a position similar to that of

the English on the Bussaco heights but instead to tempt them

to fight on more favourable ground. The rest is history.

[1] A spark from a French gun alighted on a leaking barrel of gunpowder on its way from the Cathedral, (which acted as a magazine), to the ramparts which

caused an explosion resulting in untold damage to the city.

More Bussaco and Messena

The battle on this side of the Serra was all but over. The

situation was changing fast, further down the line where the other

important action was on the British left and was as bloody as Reymer's

attack although shorter in duration. Once Ney saw the 2nd Division

massed on the crest of the plateau by the San Antonio pass he

attacked, following his orders to the letter, with two divisions, one on

either side of the Coimbra road, when he saw Merle's column massed

on the edge of the plateau. He had three divisions under him, so he

placed Loison on his right, Marchand on his left, keeping Mermet in

reserve (behind the village of Moura). Marchand's and Loison's

divisions were completely separated by a deep ravine. Marchand was

to advance along the gentle slope which led up to the Bussaco

convent. The first part of the approach was easy - up to the village of

Sula through woods and orchards. But the upper part of the route was

extremely steep, giving no cover whatsoever. It was, in fact, a

glorified mule track.

The battle on this side of the Serra was all but over. The

situation was changing fast, further down the line where the other

important action was on the British left and was as bloody as Reymer's

attack although shorter in duration. Once Ney saw the 2nd Division

massed on the crest of the plateau by the San Antonio pass he

attacked, following his orders to the letter, with two divisions, one on

either side of the Coimbra road, when he saw Merle's column massed

on the edge of the plateau. He had three divisions under him, so he

placed Loison on his right, Marchand on his left, keeping Mermet in

reserve (behind the village of Moura). Marchand's and Loison's

divisions were completely separated by a deep ravine. Marchand was

to advance along the gentle slope which led up to the Bussaco

convent. The first part of the approach was easy - up to the village of

Sula through woods and orchards. But the upper part of the route was

extremely steep, giving no cover whatsoever. It was, in fact, a

glorified mule track.

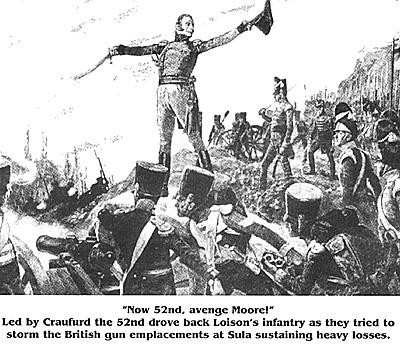

With impeccable timing, he waited until the two enemy columns had reached the last steep slope

(just below where he was standing). As the French paused to take breath before climbing the final slope, he signalled to the concealed battalions crying, so legend has it, "Avenge the

death of Sir John Moore." At once the crest became thick with rifles and the French received a tremendous volley. The heads of the advancing columns crumbled in a mass of dead and dying.

With impeccable timing, he waited until the two enemy columns had reached the last steep slope

(just below where he was standing). As the French paused to take breath before climbing the final slope, he signalled to the concealed battalions crying, so legend has it, "Avenge the

death of Sir John Moore." At once the crest became thick with rifles and the French received a tremendous volley. The heads of the advancing columns crumbled in a mass of dead and dying.

FOOTNOTES

[2] Pelet's Diary of the Spanish and Portuguese campaigns, ed by Horward, p 170

[3] Memoirs of Colonel Delagarve, p 168

[4] Lopez was an 18th century Spanish cartographer. The more accurate maps used by Junot for a previous invasion were kept safe in Paris!

[5] A large number of despatches for Paris never reached their destination, having been intercepted by guerillas.

[6] From the Archives du Ministere de la Guerre (quoted by Oman, iii, p353)

[7] The pine and eucalyptus trees, which can be seen there today, were planted later.

[8] Fririon, Campagne de Portugal - p47

[9] Koch - La Vie de Massena, vol vi, p 102

[10] As did Napoleon before the battle of Austerlitz

[11] Grattan's Adventures with the Connaught Rangers, p35

[12] Supplementary Dispatches, vi, p635

[13] Quoted unsourced by Oman, iii, p374

[14] Oman, iii, p376, unsourced

[15] Foy's diary, pp103-4

[16] Simon was so upset by his capture that he sent word to General Craufurd challenging him to a duel. The response was a deafening silence!

[17] A line of 250 fortifications around Lisbon which Wellington had been preparing, with the help of Portuguese labour since the Battle of Talavera, and about which the French knew nothing until the first week in October when they heard the news through a Portuguese deserter.

[18] Pelet complained that all orders were set out in writing and that the Commander-in-Chiff had little contact with his men. Compare with where Wellington slept the night before the battle as described above.

[19] Memoirs of Colonel Noel: p117

[20] Ibid, p 118

[21] Supplementary Dispatches - letter to William Wellesley Pole vol VI p606

Back to Age of Napoleon 30 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com