Almeida, having fallen prematurely to the French due to a lucky accident, [1] Massena, on 11th September issued an operational order for the Army of Portugal to start the next phase of their campaign: the invasion of Portugal.

Part of the force were to advance through Coimbra and

Santa Comba Mo. Reynier's and Ney's corps, with the artillery park,

escorted by Montbrun's cavalry were to go to Viseu via a more

northerly route through Pinhel and Trancoso. J-J Pelet, Massena's

senior adviser and principal ADC was not happy about this choice of

route, writing:

'I was also afraid that the Mondego would rise and fluctuate

... yet what could we do to surmount such obstacles when we could not

even predict marches of only four or five leagues on the road to

Trancoso. Every day we were supposed to leave, and each day brought

us new delays. [2]

Bad Road

Why did Massena choose such an extraordinarily bad road for his troops?

Colonel Delagarve in his memoirs suggested that:

The Serra de Alcoba route could throw up great difficulties

for the Army's passage. Apart from that, the enemy could contest our

crossing the Mondego and defend the Coimbra heights if necessary,

sacrificing the town to the realistic situation. On the other hand, the

road following the right bank offered a much greater advantage

because we were able en route to go through two rich and important

towns, Viseu and Coimbra ... which would be ideal places to set up

magazines and hospitals. [3]

When the French route became clear, Wellington wrote

gleefully to Charles Stuart in Lisbon, and two days later to Lord

Liverpool:

There are many bad roads in Portugal, but the enemy has

decidedly taken the worst in the whole kingdom.

Colonel Noel, in his memoirs, describes the route after

Trancoso as being all mountain and rock with the nearest thing

resembling a road being a stony, narrow and dangerous track;

dangerous because of Portuguese guerilla-style tactics of mounting

surprise attacks, especially, when, due to the appalling quality of the

roads, the artillery park got into difficulties. To keep the gun

carriages moving, the gunners had to repair the roads before the

convoy could move forward. The caissons were pulled by

undernourished horses which did not help matters. The group got lost,

due to the out of date and hopelessly inadequate Lopez maps [4] which misplaced some towns, missed out a number of roads that actually

existed and put in others that did not.

This problem was exacerbated by there were no local guides to fill

the gap as the local population was very hostile to the invaders.

Massena's problems were compounded by 30 Portuguese collaborators

on his staff who appeared to have no detailed knowledge of the area,

and whose knowledge of the French language was so bad that they

were of little help to their invaders. The main part of the convoy

arrived at Viseu on the 19th September: the artillery park arrived two

days later. These were not the only problems.

He hoped to replenish his resources, when he reached Viseu

but this town of 9,000 people had been deserted by the population,

and few resources were left. Not only that, but a French food convoy,

a day's march from the town, did not arrive as expected, as it had been

attacked by Trant and his partisans.

Massena's Mistress: Mme Leberton

Marbot, one of Massena's fourteen ADCs, suggests,

mischievously, that a possible reason for the delay in starting the

battle of Bussaco was that safe accommodation had to be found for

Mme Leberton, Massena's mistress, who rejoined him, having been

holed up in Salamanca during the Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida sieges.

To keep her out of harm's way during the battle of Bussaco, Massena's

headquarters were at Mortagoa, two hours hard riding time from the battlefield.

Massena was not a happy man at this stage. He wrote a

whining despatch to Berthier on the 22nd September saying that:

It is impossible to find worse roads than these; they bristle

with rocks; the guns and train have suffered severely and I must wait

for them. I must leave them two days at Viseu when they come in, to

rest themselves, while I resume my march [to Bussaco] where (as I am

informed) I shall find the Anglo Portuguese [army] concentrated.

He continued in desperation -

Sire, all marches are across a desert; not a soul is to be seen

anywhere: everything is abandoned . . . we cannot even find a guide.

Assuming that this despatch would reach the Emperor, [5] he

added, 'The soldiers are satisfied and burn for the moment when they

shall meet the enemy.' [6]

To say that the soldiers were 'satisfied' was misleading.

Because of the unscheduled delays, Massena had exhausted half the

rations he had brought with him from Almeida before the start of the

battle. The shortage, was made worse by Wellington's scorched earth

policy which meant that there was only the occasional field of

potatoes and vineyards to make good this deficit and so the French

were unable to live off the land. Because of all the problems, the

convoy did not start arriving at Viseu until the 19th September, two

days ahead of its artillery park.

Wellington's Defense

Wellington, with time on his side, courtesy of Massena, was

able to move his headquarters to the Convent on the Bussaco ridge on

the 21st September where he was to remain for the next seven days.

On the 22nd, he ordered Leith's and Hill's divisions to prepare to

cross the Mondego in order to join the rest of the army on the right

bank. He had by this time made the historic decision that the Bussaco

ridge was the ideal place from whence to tempt the enemy to give battle.

The Bussaco ridge is named after the Convent on one of its

peaks. It is a single continuous fine of heights which at the time of

the battle would have been covered with heather and furze, [7]

interspersed with many hunks of red and grey granite, extending to

the river Mondego on its right, and to the main chain of the Serra de

Alcoba on its left. It is irregular in height, intersected at its lowest

point by the San Antonio de Cantara road to Palheiros. The other

main intersection is the road close to the convent running from

Celorico to Coimbra.

Reconnaissance

On the 26th, Massena sent Ney on a reconnaissance mission

to find out how many English and Portuguese troops he would have to

face. Wellington, using his reverse slopes tactics, was able to give the

impression that only a small rearguard was left on the heights,

presumably to give the impressio* that the rest of his army were on

their way to the Atlantic ports prior to embarkation.

On the evening of the 26th, the day before the battle,

Massena held a meeting with his senior officers at which Reynier, and

General Lazsowski, the Polish commander of the engineers, favoured

Massena's idea of a frontal attack. Ney, Junot, Fririon, Massena's

Chief of Staff, and Eble, his artillery commander, were against the idea.

Massena turned on them, saying: You come from the old

army of the Rhine, you like manoeuvring; but it is the first time that

Wellington seems ready to give battle, and I want you to profit by the

opportunity. [8]

Ney considered that they should have already assaulted the

heights on that same day when Wellington would have been deprived

of some of the time advantage he had enjoyed up till then. Ney

considered that to have waited until the 27th to take on the enemy

was a missed opportunity. In any case, he argued, rather than attack

the enemy on the Bussaco heights, they would do better to strike at

Oporto which was defended only by militia.

Massena disagreed: the Emperor had ordered him to march

on Lisbon not Oporto. [9] Ney's suggestion would, he said, have

prolonged the war, not shortened it. In any case, Wellington would

probably have been able to withstand such a move. Poor Ney! The

antipathy between him and Massena was so strong that there was no

chance of his idea, however sound, even with the support of most of

his senior colleagues, being adopted at any stage. Koch, in "La Vie

de Massena" reckons that Massena's decision to attack the heights was

to assert his authority over his dissident senior commanders.

The night before the battle, Massena retired for the night to

Mortagoa, to his headquarters, ten miles from the battlefield, for the

night, some say to be with Mine Leherton, his mistress. Wellington,

Grattan tells us, slept among his troops which he says had a terrific

effect on morale. [10]

He describes the atmosphere as calm but loaded with anticipation.

Each man [slept] with his firelock in his grasp at his post.

There were no fires, and the death-like stillness that reigned

throughout the line was only interrupted by the occasional challenge

of an advanced sentry, or a random shot, fired at an imaginary foe.

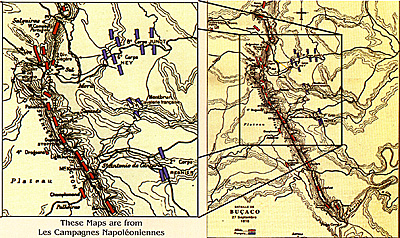

Map

More Bussaco and Messena

Back to Age of Napoleon 30 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com