By 6 June what appeared to be an adequate breach had been formed in the flank wall of the castle. Lieutenant Forster of the Royal Engineers had made a close examination of the breach and pronounced it practicable and plans were laid to assault the breach that night. 180 selected volunteers from the 85th and 51st Light Infantry Regiments, under the command of Major Macintosh of the 85th, were to form the storming party.

At the head of the attack was to be the Forlorn Hope, twenty-five men led by a single officer, Ensign Joseph Dyas of the 51st. This young subaltern was an '...officer of great promise, of a most excellent disposition, and beloved by every man in the Corps - an Irishman by birth and whose only fortune was his sword.' [4]

Instructions were given that only as a last resort should the attackers fire their muskets; speed and surprise were to be their principle weapons. To stop reinforcements reaching the Fort from the city fifty men of the guard from the trenches were posted to the west of the heights, whilst another party, with two field pieces, were to cover the river and block any attempt

by the garrison to ferry troops across by boat.

At midnight Lieutenant Forster directed the advance of the storming party from the cover of No.1 Battery towards the ditch of the fort. Visibility was good in the bright moonlight and the column moved rapidly in perfect order towards the outwork.

'We advanced up the glacis close to the walls. Not a head was to be seen above the walls, and we began to think the enemy had retiered into the town. We entered the trench and fixed our ladders, when sudden as a flash of lightening the whole place was in a blaze.'

The ditch was reported to be only four feet deep at the point of attack but to the dismay of the attackers in the time between nightfall and midnight the garrison had moved the rubble from the breach and a sheer wall seven feet high loomed depressingly above them. The parapets were '...crowed with men hurling down shells and hand grenades, whilst half a dozen cannon scoured the ditch with grape shot.' There were 'Heaps of brave felloes, killed and wounded, ladders shot to pieces and falling together with the men upon the living and the dead.' [5]

For almost an hour the attackers vainly tried to mount the walls of the fort whilst the defenders continued to shower them with anything that they could lay their hands on, even throwing stones and rubble at the seething mass below. [6]

At one stage, for a few brief moments, some men actually surmounted the breach but eventually, reluctantly, the storming party gave up the struggle and fell back with Ensign Dyas the last man to leave the breach. Altogether ninety men were wounded and thirteen, including

Lieutenant Forster, were killed, '...the place was covered with dead and dying, the old black walls and breach looked terrible and seemed like an evil spirit frowning on the unfortunate victims that lay prostrate at its feet.' [7]

Next Morning

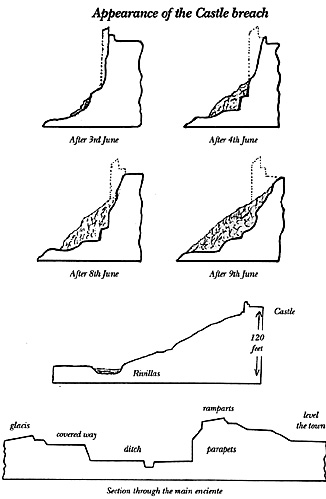

The next morning Wellington visited the forward trenches to examine the breach. Despite the debacle of the previous night he decided to persevere with the attack and so throughout the rest of the day fifteen guns played upon the scarp wall that had deterred the storming party. Battery

No.7 was completed and the iron 24-pounders were run in. The following day, the 8th, these guns began their bombardment of the castle and their effect was immediately evident. Two days later the earthen bank had been battered flat and the rubble that had collected at the foot

of the breach formed 'a road into the castle.' [8]

The guns in Batteries 1, 2 and 3 continued to extend the breach in Fort Christoval but by the 9th only thirteen guns were still in use. The breach, however, was considered practicable once again and a second assault was ordered for that night. This time Wellington ordered the attack to be made as soon as it was dark so that the garrison would have no opportunity to clear away the rubble from the breach. Dispositions for the attack were more thorough than before.

The storming party was to total 200 men including a number of French emigres of the Chasseurs Brittanigues. Detachments were to be sent towards the river and to the west of the heights, and other units were to fire against the parapets of the fort to impede the defenders. It was also

planned that as soon as the fort had been captured a company under the command of three Engineers was to make the place secure against counter-attack. So confident were the Allies of success that thirty men had orders to move round to the rear and cut off the retreat of the fleeing Frenchmen! Ensign Dyas again approached General Houstan and requested permission to lead the Forlorn Hope.

'No, you already have done enough' insisted the General, 'and it would be unfair that you should bear the brunt of this business.'

'General Houstan,' replied Dyas, 'I hope you will not refuse my request, because I am determined if you order the fort to be stormed fory times to lead the advance so long as I have life.' [9] The General relented.

A heavy fire was maintained against the breach as the storming party left their positions as soon as 'the shades of night had cast her mantle...' The 200 men carrying between them sixteen, thirty feet long ladders were divided into two equal halves each of which preceded by its own

Forlorn Hope. One half was to assault the breach the other the salient angle of the fort. As the attackers climbed the heights they were greeted by the jeers of the greatly reinforced garrison. After the constant bombardment of the preceding few days the defenders were eager to get to grips with their foes. Musket balls filled the air as the Forlorn Hope entered the

ditch.

Lieutenant Hunt of the Engineers, directing the assault, was instantly struck down but the main body was in close support and soon both groups were clambering over the rubble towards the crest of the breach. Two other officers were killed and soon all order was lost as grenades and shells fell all around them. Without direction the attack fizzled out as the men blundered around in the dark.

'The soldiers posted on the glacis, by their determined fire, notwithstanding their exposed situation forced the enemy to waver, and if ever there was a chance of success, it was at this moment. Dyas and his companions did as much as men could do, but in vain. Their efforts were heroic, though unavailing; the spot was strewn with dead and dying; the breach was packed with Frenchmen, and the glacis and ditch covered with our dead

and disabled soldiers. Major McGeechy fell pierced with bullets, and almost all the party shared his fate. Ensign Dyas was struck by a pellet in the forehead, and fell upon his face, but undismayed by this, he sprang up and rallied his few remaining followers, but in vain.' [10]

An hour later the remnants of the storming party staggered down from the heights. Only sixty had survived, amongst them Ensign Dyas. 'How he escaped unhurt is a mystery. He was without cap,

his sword scabbard was gone, and the laps of his frock coat were perforated with balls.' [11]

For the rest of the war the Peninsular army was to toast the exploits of Joseph Dyas, and even up to recent times his regiment - the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry - drank in silence a special toast to 'Ensign Dyas and the Stormers.'

The next morning Wellington called together all the senior commanding officers. Although the castle walls had been well breached by the regular pounding of the iron guns, French deserters revealed that behind the breach was '...a solid rock which would take six months battering.' [12] As Christoval was still in enemy hands it would have been suicidal to attempt to mount such an obstacle. It was obvious that before the fort could be taken, more extensive preparations would have to be made and circumstances no longer permitted such lengthy operations for only a few miles to the north the storm clouds were gathering. The combined armies of Soult and Marmont - 60,000 men - were about to burst upon them.

Allied Withdrawal

On 12 June the Allies began their gradual withdrawal back across the Guadiana. A few days later the evacuation was complete and, on the 19th, the French armies marched into Badajoz where the garrison were nearly out of food and the Governor, General Phillipon, had lost all hope of being relieved and had planned to break out and escape. The siege had cost the Allies 485 men killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The lack of trained and experienced personnel and the sorry

state of the siege guns were amongst the principal factors in the Allies' failure to capture Badajoz. Wellington had only twenty five men of the Royal Corps of Military Artificers and no less than eighteen guns had been disabled by their own fire.

Notwithstanding these handicaps the Engineers were severely criticised in the English press. 'Had the Engineers followed the rules of fortification with as much ability as his lordship displayed in his application of the principles of the higher branches of tactics,' wrote a contemporary, 'Badajoz would, no doubt have surrendered about the 14th or 15th of June. It scarcely would be believed, were it not expressly mentioned in the official reports, that in the beginning of the nineteenth century, troops should have been sent to the assault with ladders

after the breach had beenjudged practicable.' [13]

But, above all, time was the single most important element in the whole operation and it could be argued that considering the military situation in the Peninsula in the summer of 1811 this first attempt upon Badajoz by the Allies was premature.

Almost a year later, in the spring of 1812, Wellington once again threw his men at

the mighty walls of Badajoz. On this occasion, though, a large siege train consisting

of sixty-eight modern iron guns and howitzers was available to Wellington, as well

as more Engineers, more Artificers and, most especially, more time.

[1] W. Wheeler, The Letters of Private Wheeler, London 1951 REFERENCES

[2] J. Colville, Portrait of a General. Sailsbury 1980

[3] Lt.-Col. Gurwood, The Dispatches and General Orden of

Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. London 1841

[4] Wheeler P.61

[5] Ibid P.64

[6] Grattan of the 88th Regiment stated that Lieutenant

Forster was mortally wounded as soon as the attack reached the glacis and as aresult the main body, with no-one to direct them, mistook a damagedembrasure for the breach, which was why the wall was higher than anticipated. Other contemporary accounts, though, do not support this view. (W. Grattan, Adventures with the Connaught Rangers, p.98)

[7] Wheeler P.61

[8] J.T. Jones, journal of the Sieges Undertaken by the Allies in Spain the years 1811 and 1812. London 1814

[9] Wheeler P.63

[10] Grattan P.99-100

[11] Wheeler P.64

[12] Jones P.59

[13] See J. Grehan, The Forlorn Hope. London 1990

Quotes from The Letters of Private Wheeler by permission of David Higham Associates limited.

Quotes from Portrait of a General by permission of Michael Russel (Publishing) limited.

In part 1 of this article, I wrote that the British miners used dynamite to blast through rock to form their trenches. Alfred Nobel did not invent dynamite until 1867. I, of course, meant gunpowder. My apologies. J.G.

Return Fire: 1st Siege of Badajoz

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #3 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1991 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com