The Duke of Wellington, possibly more than any commander before him, was regarded as an assiduous general, a man who never undertook an operation that was not carefully considered nor thoroughly planned. Yet in 1811, Wellington laid siege to the fortress of Badajoz with an army that was ill-prepared and inadequately equipped for siege warfare and as a result the enterprise proved a costly failure. This article examines this rare defeat for Britain's most successful military leader.

For three years, since August 1808, a small British army led by the future Duke of Wellington had fought to defend Portugal from the mighty legions of the Emperor Napoleon. Three times the French had invaded Portugal and three times they had been driven back into Spain, and now Wellington believed that his Anglo-Portugese army was strong enough to move onto the offensive. But before he could advance beyond the Portuguese frontier to attack the widely dispersed French forces Wellington had to take control of the border fortresses of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz that guarded the two main invasion routes into Spain.

Ciudad Rodrigo had been captured by the French the previous year and Badajoz, although still in Allied hands, was under siege and likely to fall to the enemy at any time. Wellington moved the bulk of his army towards Ciudad Rodrigo in the north of the country and dispatched General William Beresford with an AngloPortuguese force of 22,000 men to relieve the beleagured city of Badajoz. Beresford arrived before the walls of Badajoz on 25 March 1811, only to find that the place had already surrendered and the battlements manned by French infantry. So the man who had been sent to succour the fortress now had to attack it.

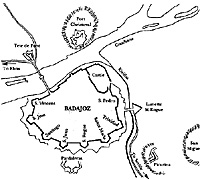

Badajoz stands on a low ridge that forms the last spur of the Toledo range. It was the largest and most formidable fortress along the entire Portuguese-Spanish frontier and its importance

lay in the fact that it sat astride the main southern highway from Lisbon to Madrid.

Badajoz stands on a low ridge that forms the last spur of the Toledo range. It was the largest and most formidable fortress along the entire Portuguese-Spanish frontier and its importance

lay in the fact that it sat astride the main southern highway from Lisbon to Madrid.

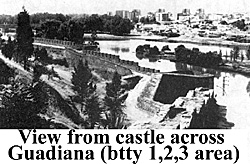

Along approximately a quarter of the city's perimeter the Guadiana river, nearly 500 yards wide at this point laps right up to the wall, rendering this sector virtually unassailable.

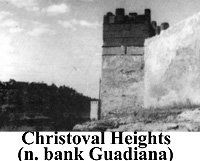

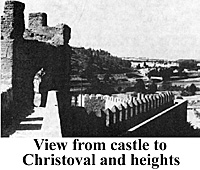

On the highest part of the ridge, at the northeastern corner of the city, stands an old Moorish castle whose ancient walls still dominate the steep, rocky hillside. The main curtain walls date back to Medieval times but, in 1757, the King of Spain ordered the fortifications of Badajoz to be rebuilt and eight strong bastions were added, each with walls thirty feet high above a ditch another twenty five feet deep. To further deter an attacker the city was also protected by four outworks; Fort Picurina, approximately 400 yards south-east of the main defences, Fort Pardaleras, 200 yards to the south, the lunette San Rogue, 100 yards due east of the walls and Fort Christoval, 500 yards north of the castle on the far bank of the Guadiana.

Beresford's first task was to seal off the

city, which meant that he would have to place a

significant proportion of his force on the

opposite side of the Guadiana. The only bridge

in the area ran directly into Badapz and

Bereeford had no bridging equipment and the

river was prone to flooding at this time of the

year. Bereeford ordered his Engineers to scour

the district and at the Portuguese fortress of

Elvas, some ten miles west of Badajoz, a few old

boats and four dilapidated pontoons were

discovered. From these bits a flying bridge was

put together and trees were felled to form a

fixed bridge on trestles. On 3 April the trestle

bridge was thrown across the river under cover

of an intense bombardment. During the night however, the river began to rise and continued

to do so throughout the next day. Eventually

the river swept right over the planking and the

bridge had to be abandoned. It was decided to

cancel the bridging operation and ferry the

troops across in whatever craft could be made available.

Beresford's first task was to seal off the

city, which meant that he would have to place a

significant proportion of his force on the

opposite side of the Guadiana. The only bridge

in the area ran directly into Badapz and

Bereeford had no bridging equipment and the

river was prone to flooding at this time of the

year. Bereeford ordered his Engineers to scour

the district and at the Portuguese fortress of

Elvas, some ten miles west of Badajoz, a few old

boats and four dilapidated pontoons were

discovered. From these bits a flying bridge was

put together and trees were felled to form a

fixed bridge on trestles. On 3 April the trestle

bridge was thrown across the river under cover

of an intense bombardment. During the night however, the river began to rise and continued

to do so throughout the next day. Eventually

the river swept right over the planking and the

bridge had to be abandoned. It was decided to

cancel the bridging operation and ferry the

troops across in whatever craft could be made available.

On 20 April Wellington galloped down from his headquarters near Almeida to assess the situation for himself. With the main body of his army almost 150 miles away and Marshal Soult known to be gathering a large force for the relief of the threatened city, Wellington demanded immediate action. He called for a plan of attack that would require no more than sixteen days of open trenches. Any operation that took longer than this would not allow Beresford sufficient time to storm the city and shore up the breaches before Soult would be upon him.

Wellington's Chief Engineer, Sir Richard Fletcher, was not in favour of a direct attack upon the city. Any attack upon the southern side of the city would necessarily involve the capture of either the Panlaleras or Picurina outworks before the main walls could be approached. This, Fletcher estimated, would take a minimum of four days. Even then the old curtain was was so well flanked by basdons that, as well as breaching the curtain, at least one of the bastions would abo have to be destroyed. Altogether this would take in excess of eighteen days.

Fletcher, therefore, proposed to assault the fort on the Christoval Heights which, he believed, could be taken by escalade after a preliminary bombardment. The heights overlooked the castle and a battery established there would easily be able to batter a hole in the weak, ageing castle walls in a matter of days. The castle dominated Badajoz and its occupation by an attacking force would render the city defenceless. After a close reconnaissance of Fort Christoval and the proposed positions for the breaching batteries, Wellington agreed to go ahead with the plan. He spent the next two days drawing up detailed instructions for the siege and then on the 25 April he galloped back to Almeida.

Beresford was left with sole responsibility for the execution of the siege and he had been promised the assistance of the local Spanish army of General Blake should he be obliged to face Soult before the city had been taken. The force at his disposal consisted of the 2nd and 4th Divisions and Hamilton's Portuguese Division as well as two brigades of cavalry, forty seven officers and men of the Royal Engineers and four brigades of artillery. He was, though, inadequately supplied with equipment. Because the British foothold in the Peninsula had been so precarious, it had not been considered wise to land expensive siege guns which, being difficult to transport might have had to be abandoned in the event of a hasty evacuation.

Beresford was left, therefore, to appropriate what he could from the locality. Elvas, being a fortress of some importance, was expected to be able to provide all that Beresford might require. All the weapons found at Elvas, however, were old brass cannon many of which were cast at the beginning of the previous century and some even dated back to the days of the Spanish Armada. The windage - the gap between the bore of the gun barrel and its respective projectile - was found to vary from gun to gun and a good deal of sorting and measuring was needed to match up sufficient suitable ammunition.

Eventually sixteen 24-pounders, eight 16-pounders, two 10 inch howitzers and eight 8

inch howitzers were selected and made ready for transportadon to Badajoz. The other essential

pieces of equipment, the gabions that would be used in forming the siege trenches, the gun

platforms, facines and splinter-proof timbers for the gun emplacements, were also in limited

supply.

Eventually sixteen 24-pounders, eight 16-pounders, two 10 inch howitzers and eight 8

inch howitzers were selected and made ready for transportadon to Badajoz. The other essential

pieces of equipment, the gabions that would be used in forming the siege trenches, the gun

platforms, facines and splinter-proof timbers for the gun emplacements, were also in limited

supply.

On 4 May MajorGeneral Stewart with the 5,100 men of the 2nd Division invested the south side of Badajoz and, three days later, the dragoons of Lumley's cavalry division sealed off the northern side after a brisk action against a French cavaby detachment that was eventually driven back into the city. All communications between Badajoz and the outside world were now cut and the siege had begun in earnest. Whilst Beresford, though, had been struggling to cross the river large stocks of food and ammunition had been rushed into the city and reinforcements had brought the garrison up to a strength of around 4,000.

With time being at a premium, it was important for Beresford to disguise the true direction of the main assault. If the garrison became aware that the prime objective was the castle, a second and possibly even a third line of defence could be prepared within the walls.

With time being at a premium, it was important for Beresford to disguise the true direction of the main assault. If the garrison became aware that the prime objective was the castle, a second and possibly even a third line of defence could be prepared within the walls.

In an attempt therefore, to conceal his intentions Beresford decided to mount diversionary actions against both the Pardaleras and Picurina outworks. Both these and the main attack were to start simultaneously. For the attack upon Christoval a battery of three 24-pounders and two 8 inch howitzers were to be used. Both batteries for the attacks upon the other two outworks were to consist of three 24-pounders and one howitzer.

As soon as darkness fell on 8 May the working parties crept towards the tall foreboding walls. The old French trenches opposite the Pardeleras were to be re-dug but fresh trenches would have to be hewn out of the tough, rocky ground around Christoval, where the 400 men of the working party soon came under an intense bombardment. So accurate was the fire from the fort and so resistant was the ground that by daylight only enough cover had been dug for ten men. Heavy fire from Christoval made work practically impossible throughout the day but the following night, under the cover of darkness, the positions for the battery were extended.

An armed body of troops was brought forward to act as a guard in case of sudden raids by the defenders but because of the difficulties experienced by the working party, insufficient cover had been provided for the guard so they had to be stationed some distance to the rear of the trenches. The garrison saw this as their opportunity. At 7 o'clock on the morning of the 10th, 700 French infantry with two field-pieces from Christoval made a daring assault upon the Allied positions. Before the armed guard could move forward, the French were in the trenches. They had little time, however, to do much damage for the guard was soon charging into the rear of the battery. After a brief struggle the Frenchmen evacuated the position and fled back to the fort.

Led on by their officers the guard chased tbem back as far aa the foot of the walls where they were met by a hail of fire from the defenders on the battlements. This irresponsible and quite unnecessary pursuit cost the armed guard over 400 men killed or wounded. But Beresford had learnt his lesson and the guard was strengthened and a small battery of 12-pounders was erected to provide covering fire.

By the morning of the 11th May the main battery was ready. At first light the guns opened up against the short flank wall of Christoval whilst the howitzers shelled the ramparts to reduce the defenders counter-fire. The day was a disaster. All three cannon and one of the howitzers were disabled by accurate gunnery from the French artillery both in the fort and from the battlements of the castle.

The feint attacks, ironically, had both begun

successfully. Two batteries had been erected

without difficulty and a heavy fire maintained

against the outworks. The rouse had obviously

paid off as the garrison had devoted equal energy

to the defence of all three forts. Beresford

decided that it was no longer necessary to

continue with the presence and all the artillery

could now be moved across to support the

attack upon Christoval. But this was not to be.

Soult, who had been moving up country rapidly,

was nearly upon them. On the 13th, Beresford

had to accept that he would not have enough

time to take Christoval, let alone the castle,

before souls would be within striking distance.

The feint attacks, ironically, had both begun

successfully. Two batteries had been erected

without difficulty and a heavy fire maintained

against the outworks. The rouse had obviously

paid off as the garrison had devoted equal energy

to the defence of all three forts. Beresford

decided that it was no longer necessary to

continue with the presence and all the artillery

could now be moved across to support the

attack upon Christoval. But this was not to be.

Soult, who had been moving up country rapidly,

was nearly upon them. On the 13th, Beresford

had to accept that he would not have enough

time to take Christoval, let alone the castle,

before souls would be within striking distance.

Wellington had advised Beresford where to concentrate his forces in the event of an attack from the south. Beresford, though, had been given full discretionary powers and he could therefore drop back into Portugal if he felt that he might be overwhelmed. He chose to fight.

Battle

On 16th May the armies of Soult and Beresford met at Albuera, fourteen miles south of Badapz. After one of the closest fought battles of the entire war, Soult withdrew having lost almost a third of his 24,600 men. Beresford's losses were equally severe. Of the 6,500 British infantry that had born the brunt of the action scarcely 2,000 had arrived.

When, three days later, Wellington arrived at Elvas he found Beresford still suffering from shock of that terrible battle. To add to Beresford's misery the garrison of Badajoz had taken advantage of the situation and had levelled all the siegeworks and re-built the damaged walls. Many of the townsfolk had also been seen assisting the French in their repair work which could only mean that the inhabitants were prepared to support the garrison throughout a long and bitter siege.

The Allied force in the south was increased to 24,000 when the 3rd and 7th Divisions arrived at Elvas on the 24th. 10,000 of these troops, under Major-General Hill, were dispatched to observe souls's movements and to prevent him from again disrupting operations, whilst of the remaining 14,000 men that were to comprise the besieging force, almost 5,000 were allotted to the Christoval sector. The rest of the force, under Picton (3rd Division) and Hamilton (7th Division) crossed over the Guadiana by a ford above the town and invested Badajoz on the south-eastern side. From the Christoval heights it could be seen that the garrison had not erected any form of secondary defence within the castle walls and, for the first time, hopes ran high of an early victory.

The city was fully invested by the 27th and, three days later, on the night of the 30th May, the first of the working parties moved into action. Wellington had decided to continue with the attack upon Christoval and the castle, for time was still an influencing factor in Wellington's deliberations. Although none of the French armies operating in Spain could, individually, pose any immediate threat to Wellington, it was always possible that Soult would pin forces with Marshal Marmont to put together a force of overwhelming strength for the relief of such a strategically important fortress.

Had time not been of such importance, Wellington could have adopted more orthodox tactics and attacked the southern side of the city as Soult had done earlier in the year. But it had taken the French from 30th January until 11th February to capture the Pardaleras fort so all that Wellington could hope to do was to have a large enough hole in the castle walls and throw his men at the breach. This time, though, there was to be no effort wasted on diversionary actions and every gun was to be brought to bear upon either Fort Christoval or the castle.

Had time not been of such importance, Wellington could have adopted more orthodox tactics and attacked the southern side of the city as Soult had done earlier in the year. But it had taken the French from 30th January until 11th February to capture the Pardaleras fort so all that Wellington could hope to do was to have a large enough hole in the castle walls and throw his men at the breach. This time, though, there was to be no effort wasted on diversionary actions and every gun was to be brought to bear upon either Fort Christoval or the castle.

Once again the antique brass guns of Elvas had to be dragged to Badajoz, putting further strain upon their old, and rapidly falling, wooden carriages. This time no less than thirty 24 pounders, four 16-pounders and four 10 inch and eight 8 inch howitzers were made available. In addition to this six modern iron 24pounder naval guns were on their way from Lisbon, along with a company of the Royal Artillery, and were due to arrive at the front within the next few days.

On the night of the 30th two trenches were begun, one in front of the castle, the other along the lower slopes of the Christoval. Over by the castle the workmen went about their tasks so quickly and quietly that it was not until the next morning that the garrison woke up to find a parallel, over 1,000 yards long, had been dug only 800 yards from the castle walls. Across the river the attack upon Christoval had been considerably less successful.

Immediately the workmen attempted to

break ground, the garrison were alerted. Little

progress was made against the hard ground and

the deadly French cannon, and the Allies

suffered heavy losses '...it is a saying the more

danger the more honour,' remarked one of the

working party that night, 'so this must be the

most honourable job we could have been set

about' [1] since the previous siege the garrison

had removed all the local topsoil and although a line of gabions filled with soil brought from the rear was placed in front of the workers they were easily knocked aside by the heavy French

cannon balls.

The following day work continued on both

parallels. Four batteries were to be erected in the

Christoval sector. One was to enfilade the

castle's defences, one to destroy the parapets of

the fort, one to breach the exposed flank of the

fort and the last to enfilade the bridge across the

river which represented the only link between the town and the fort.

Work was maintained throughout the following night and Battery No.4, being opposite the bridge and some distance from Christoval, was completed. Progress continued to be very limited on the other batteries with soil having to be carried to the front by hand. It was hard and dangerous work even for the senior officers. Command in the trenches was entrusted to the Brigadier Generals, each having to operate for twenty four hours at a time.

General Colville described conditions in the

trenches, '...you must either be exposed without

any cover at all to the almost incessant fire of

shot and shells, or take what cover is offered

behind the batteries or in the ditches at best a

partial one and especially for shells, and where

in addition to the torrid heat by day and the

dews of night, you are half suffocated between

the dust kicked up by the aforenamed visitors

and by the efflusia of three or four thousand

men, half of them Portugese, the filthiest

nation upon earth.' [2]

The first battery that was completed, armed

and ready to fire was Battery No.5 of twenty

heavy guns and howitzer that on 3 June began

the bombardment of the castle. The other four

batteries were completed shortly afterwards, the

besiegers having had to resort to employing

miners to blast through the solid rock of the

heights with dynamite. The old castle walls

appeared to be even weaker than anticipated and

by nightfall on the 3rd the outer face had been

completely smashed down. It was discovered,

however, that the walls were constructed from a

natural bank of earth which had been cut

perpendicularly and merely faced with stone.

For two days Battery No.5 continued to

beat down the bank of earth. The parallel was

pushed 150 yards nearer the castle and four 24-pounders were moved up to form Battery No.6.

The rate of fire was agonisingly slow due to the fragile condition of the old guns and it was only possible to fire one shot every eight minutes. If the gunnen exceeded this level the soft brass of the barrels would overbeat causing the muzzle to droop. Five 24 pounder were crippled in this way and three of the 10 inch howitzers smashed their carriages, another 24pounder blew its bush and accurate fire from the fort eliminated one of the 8 inch howitzers.

'Badajoz may fall,' Wellington wrote in a letter to Lisbon, 'but the business will be very

near run on both sides... I have never seen walls bear so much battering nor ordnance, nor

artillery, so bad as those belonging to Elvas.' [3]

Fortunately the iron naval guns had almost reached the front and Battery No.7 was erected to accommodate them, only 520 yards from the walls of the castle.

[1] W. Wheeler, The Letters of Pivate Wheeler, London 1951

Quotes from The Letters of Private Wheeler by permission of David Higham Asso. Limited.

Return Fire: 1st Siege of Badajoz

References

[2] J. Coville, Portrait of a General. Salisbury 1989

[3] LtGen Gurwood, The Dispatches and General Orders of

Field Marshal the Duke of Wellington. London 1841

Quotes from Portrait of a General by permission of Michael Russel (Publishing) Limited.

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #2 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com