Withdrawal

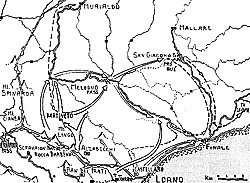

Against the French columns spread on the

roads and the ridges, D'Argenteau had an available

fighting force of not more than 2,000 men, now

lacking in supplies and ammunition. The Austrian

General found it practically impossible to reorganise

the front. The only possibility he had of holding the

French back was to withdraw along the valley of

Bormida to the village of Calizzano. Then, since he

was threatened by the Republican column that

had arrived at Melogno Pass, to that of Murialdo, about 30 kilometres north of the positions

held that morning. Not only was the Imperial centre routed, but

towards evening the flank of General Wallis was also left exposed,

with the remnant of the Army of Lombardy scattered along the coast.

Against the French columns spread on the

roads and the ridges, D'Argenteau had an available

fighting force of not more than 2,000 men, now

lacking in supplies and ammunition. The Austrian

General found it practically impossible to reorganise

the front. The only possibility he had of holding the

French back was to withdraw along the valley of

Bormida to the village of Calizzano. Then, since he

was threatened by the Republican column that

had arrived at Melogno Pass, to that of Murialdo, about 30 kilometres north of the positions

held that morning. Not only was the Imperial centre routed, but

towards evening the flank of General Wallis was also left exposed,

with the remnant of the Army of Lombardy scattered along the coast.

On the 22, General Pierre Francois Charles Augereau had concentrated his 7,000 armed men against the balance of the Army of Lombardy, estimated at about 13,000 men. At 06.00 on the 23rd the French line initiated its attack. Augereau used only two of his four brigades.

That of General Bannel attacked Toirano, and that of General Rusca, Boissano. Both efforts were successful and the Austrians were driven back beyond the gorge made by the Varatella, between the houses of Toirano. General Bannel, wounded in the course of action, was replaced by Colonel Jean Lannes. A rising star from the revolutionary armies, he now had the opportunity to show the courage and tactical ability that characterised his career.

The Imperials were compelled to barricade themselves in the nearby Charterhouse. Colonel Lannes, ignoring this garrison, continued his impetuous advance on the cliffs above Loano, destroying the strongpoints of the line of defence and those units routed by Massena who were withdrawing to the coast.

Nearer the Sea

Nearer the sea, General Rusca was advancing, supported by the reserve of General Dommartin. The latter was at last involved in the fighting around the Charterhouse of Toirano, from which Austrian General Ternyey had led an attempted sally. Having forced back the demibrigade left by Lannes to besiege him, he could have succeeded in escaping had he not been impeded in his withdrawal towards Loano by hospital personnel and wounded soldiers of a republican field infirmary. At this point Dommartin intervened driving the Imperials back to the Charterhouse and then by cannon shots forcing then to surrender.

The brigade of General Claude-Victor Perrin "Victor" held the extreme right of the French front. He developed his own action against Loano with the support of about ten small gun-boats who, tacking near the coastline, created a disturbance without actually inflicting any real damage to the Austrian defence.

The republican troops attacked on favourable ground for cavalry, so that two squadrons of Austrian Uhlans and a regiment of Neapolitan Dragoons succeeded in driving back Victor's attacks three times. The cavalry action, although contained by French light infantry fire, galvanised the Imperial regiment surrounded on nearby Mount Castellaro. In the afternoon they succeeded in forcing their way through the besieging Republicans and joined with the Austrian defenders of the fortress of Loano. They were heedless of the fact that they would have to pay the high price of many lives.

More or less all the French line was marching forward, but the prudent Scherer did not yet have a clear view of the situation. By mid- ahernoon, therefore, he stopped the troops that he was able to reach, instructing them to hold their positions This convinced Wallis that, after a night of reorganisation, the Imperial units would be able to counterattack. The Austrian commander then learned of the fall of the Charterhouse of Toirano and of D'Argenteau's disaster. At that moment D'Argenteau was rapidly withdrawing without worrying about keeping the way of escape open for the Army of Lombardy.

Disordered Withdrawal

During the night, amid the pouring rain that had started during the ahernoon, Wallis withdrew in a disorderly manner towards the village of Finale. The French columns, in sprte of their confusion, were impetuously advancing. Massena found himself in a suitable position to give a coup de grace to the Austrians. However, with his exhausted troops and a ratio of more than three to one to his disadvantage, he considered it expedient to await reinforcements and the new day before resuming action.

The Austrian retreat re-commenced the morning of the 24th. Like D'Argenteau, Wallis also sought to reach the valley of Bormida and he therefore despatched a strong vanguard to guarantee possession of the Pass of San Giacomo. Due to the lack of aggressiveness of General Pittoni, its commander, and Massena's impetus, assisted by Laharpe and Charlet, the Austrians were prevented from reaching the pass.

The French attack routed the Austrians, driving them back towards the sea, all the time losing men and materials. Wallis' routed troops were running towards Savona, on the only remaining coast road.

The shortage of French provisions and supplies, and the exhaustion of their units permitted the Allied armies to reorganise themselves. On the 25th the Imperials withdrew to Savona and Vado, where they burned depots, and then resumed their retreat towards the Pass of Cadibona. The troops of Generals Pittoni and Rukavina performed an effective rearguard action because the exhausted French were unable to develop a strong attack. The survivors of the Austrian units arrived at their base in Acqui on the 29 November.

For his part General Colli, who for all of the 24th remained

without news of Wallis, began to reorganise his own lines. He

recalled troops from the valleys that extended towards Tenda Pass,

certain that the heavy snowfall had impeded French movement in

that area. Ignoring his own disastrous state, Colli even considered a

counterattack. Once he appreciated the situation on the 25th the

Piedmontese commander created a flank defence in the valley of

Tanaro, parallel to the withdrawal of D'Argenteau along the Bormida

valley.

For his part General Colli, who for all of the 24th remained

without news of Wallis, began to reorganise his own lines. He

recalled troops from the valleys that extended towards Tenda Pass,

certain that the heavy snowfall had impeded French movement in

that area. Ignoring his own disastrous state, Colli even considered a

counterattack. Once he appreciated the situation on the 25th the

Piedmontese commander created a flank defence in the valley of

Tanaro, parallel to the withdrawal of D'Argenteau along the Bormida

valley.

The intention of Colli to hold his own position was soon revealed as an illusion. During the night of 27/28 November, Scherer, convinced that he was unable to pursue the Austrians further, despatched strong contingents against the Piedmontese. By mid- morning of the 28th, Miollis had taken the positions that had been uselessly attacked on the 23rd and had driven his men to outflank the left of the Tanaro.

More Retreat

At that point the Piedmontese, threatened by encirclement, abandoned Mount Cianea, San Bernardo Pass and the village of Garessio to retreat to Mount Spinarda. The positions were immediately occupied by the right flank of the pursuing French, but the most dangerous push came from the troops on the road from Garessio leading to Ceva, resolutely led by Serurier.

In the end Ceva became the mainstay of the line of defence that Colli was forced to form, and which would become the stage of the battles of the following spring. The 29 November was the day that concluded operations. The Austrians had repaired to Acqui, the Piedmontese were lined up in secure positions and the French had exhausted their energies and resources necessary to feed a further offensive.

At Loano between the 23 and 29 November (2/8 Frimaire, according to the calendar of the Revolution) 1795, General Scherer achieved a noteworthy success. This is confirmed by the figures: 5,500 Imperials dead, wounded and imprisoned; 500 French dead, 800 wounded and 400 imprisoned, a ratio decidedly favourable to the latter, especially if one considers that they were attacking. In addition, the Austrians lost their Ligurian depots, as well as 48 guns and 100 caissons, which represented practically the whole artillery-park of the Army of Lombardy.

Fatal Consequences

This loss resulted in fatal consequences for the Imperials during the following spring's campaign against Napoleon. It was Napoleon, however, who bitterly criticised Scherer for not exploiting Massena's victory. After Loano, thundered Napoleon, it was necessary to pursue the Piedmontese preventing them from forming a new line in the area of Ceva. This would have forced Victor Amadeus Ill of Savoy, King of Piedmont, to make a treaty with France, and would have isolated the Austrians in Italy.

Protested into Promotion

The young general protested so much that in the end he was given the command of the Armee d'Italie and thus the responsibility of realising his own ideas. For his part, Scherer remained of the opinion that the condition of the troops did not allow for a further effort and he continued to urge the despatch of reinforcements and supplies. In the end, as his requests were not satisfied, Scherer resigned leaving the Armee d'Italie to face a hard winter in the mountains between Liguria and Piedmont. Augereau was given the credit for maintaining cohesion of the units in the cold and left practically without supplies.

From the Battle of Loano it became evident that the heavy line formation, applied without any flexibility by the elderly Austrian commanders, was becoming altogether insufficient to contain the dynamic tactics of the French. The demi-brigades were quickly evolving their own tactics, passing from the disorderly mass of the first revolutionary armies to very manoeuvrable and flexible units. Without doubt, this result was accredited to the ability and decision of the officers who were emerging from the tough selection of the revolutionary wars.

If the cycle of operations of 1794/1795 appears to be constantly influenced by the will of Napoleon, one must not forget the determined action of men who rapidly found themselves collaborating with Buonaparte and whose glory and fame grew alongside his own. Of the twentysix Marshals who were nominated by Napoleon, the following were at Loano: Massena, Serurier, Augereau and Victor with the rank of general, Lannes and Suchet were colonels; whilst Kellerman and Berthier, also generals, were indirectly involved.

It is certainly significant that such a large number of men destined to be successful were in that battle. Not to be overlooked are other less fortunate commanders of great value who distinguished themselves at Loano. Among these was General Charlet who was killed on the 23 during the arduous encounters of the Alzabecchi, his colleagues Bannel and Laharpe who fell in the campaign of 1796 and also Joubert, who was killed in the Battle of Novi in the summer of 1799.

Visiting

Visiting the locations of the battle of the 23rd to 29 November 1795, is not an easy matter because of the steep nature of the terrain on which they occurred. In addition, the contradictory reports of some writers have created uncertainties that have only recently been clarified by careful research conducted by local members of the Napoleonic Association of Italy.

The difficult mountain road from Loano to Garessio leads to the locations of some of the encounters. It passes through a landscape that is as much severe as it is rich in splendid views, in which interest in history overlaps with natural beauty. A few kilometres outside Loano, one sees the remains of the Charterhouse. The church with its white walls and caved-in roof survives in a state of abandonment on the road, within the boundary of Toirano, ascending to the Saddle of the Alzabecchi and leading to Bardineto.

At Bardineto, where the troops of D'Argenteau withdrew in the afternoon of the 23, there are some battery positions which are often accepted as being from the Napoleonic era. They are, however, part of a nineteenth century firing range of the Piedmontese artillery.

Following the valley of Bormida in the direction of Erli, one reaches the Scravaion Pass. Here, immediately at the back of the maintenance worker's house, one finds the remains of four Austrian artillery positions, arid two Piedmontese. Other positions, less easily accessible, remain on the ridge of the mountains of Lingo, Schenasso and Subanco, cut by the Scravaion Pass.

A few kilometres from the pass, on an abutment jutting out from the side of the Neva valley, rises Rocca Barbena. This is a small and ancient village with houses clinging around the ramparts of an imposing castle.

The winding road follows the ascent to the San Bernardo

Pass, dominated on the right by Mount Cianea, on which there are

traces of trenches. To reach these positions one needs to abandon

the car, without attempting to use the prohibited road of the Forest

Warden. The same applies if one wishes to see the most interesting

works of Mount Spinarda where, in addition to the trenches, there is

a redoubt notable for the height of its dry stone walls. It was

constructed by the French and was repeatedly lost and retaken by them.

The winding road follows the ascent to the San Bernardo

Pass, dominated on the right by Mount Cianea, on which there are

traces of trenches. To reach these positions one needs to abandon

the car, without attempting to use the prohibited road of the Forest

Warden. The same applies if one wishes to see the most interesting

works of Mount Spinarda where, in addition to the trenches, there is

a redoubt notable for the height of its dry stone walls. It was

constructed by the French and was repeatedly lost and retaken by them.

More commitment, however, is required if one includes in the itinerary an interesting excursion on foot. Leave from Cape Santo Spirito, by the sea near Borghetto, ascend Mount Croce and then head for the mountains of Monte Acuto, Poggio Grande and Rocca Grande.

Next to the sanctuary of Our Lady of Balestrino, one finds the stronghold called "Little Gibraltar", which some historians have incorrectly located elsewhere, although nineteenth century sources clearly demonstrate its placing in this area. At last one reaches Pian dei Prati, beautifully positioned under the landscaped outline, where one can observe most of the front and also nearby the remaining traces of trenches and encampments.

Farther to the East, above Finale, ascending from Feglino for the road from San Giacomo to the Melogno Pass, one passes Pro Bue, where the Austrians abandoned their artillery. All across the vast area where the battle was fought there are various fortifications. They, like the fortress blocking the road from Toirano to the sea, are of slightly more recent construction, being built during the French/Piedmontese crisis of 1800. This was when the more important Apennines passes became fortified, with particular reference to those used by theFrench precisely in 1795.

More Loano

-

Battle of Loano (I)

Battle of Loano (II)

Loano Order of Battle

Re-enactment Photos (extremely slow: 743K)

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 21 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com