This colorful episode marks the beginning of the bi-centary celebration of

the Battle of Loano, a little know victory but the first engraved on the Arc de

Triumphe in Paris. Although not present at the battle, Napoleon gave strategic

direction and planning for the series of battles that opened up the following

year's campaign for Italy.

At the end of the 18th Century, each frontier of the Republic that had

arisen from the Revolution constituted a front. The Italian frontier was no

exception. Because of the nature of its geophysical terrain and the relatively

little importance given to Piedmont as an adversary, the operations languished

and the French Ministry of War considered them of secondary importance. By

chance, at the beginning of 1794, the ambitious General Buonaparte was

assigned as Artillery Inspector of the Army of Italy.

Insecurity

The assignment was ill-suited to produce battlefield laurels. Napoleon, in

order to impose his own operational ideas, knew how to play on the insecurity

that the political leadership had instilled in its generals. Dismissals,

imprisonment and the guillotine were often the lot of unsuccessful

commanders. He first gained the support of the political commissars Cristoforo

Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre (the brother of Maximilien Robespierre).

Then he succeeded in persuading General Pierre Dumerbion, the

Commander of the Armee d'Italie, to accept his scheme of a diversion on the

strong positions of the Piedmontese in Saorgio, against which French attacks

had failed for two years. In the meantime, the main effort would be developed

on the coast in the direction of Savona. About two weeks later General Andre

Massena reached Loano and, at the beginning of May 1794, he took the

mountain passes which gave access to the Pianura padana, the plain of the

River Po. Napoleon had wanted the campaign to continue, but his peremptory

suggestions went against Minister Lazare Carnot's intentions.

Carnot was convinced that it was not worthwhile sacrificing forces

on the Italian front which could affect the one on the Rhine. Buonaparte's view

was that the war against Austria had to be won, but by forcing that country to

withdraw from the Rhine in order to plug the gap in Italy.

Napoleon's viewpoint was one of grand strategy, ranging far and

wide over broad horizons. In the meantime the General was sent to Genoa

to occupy himself with less important administrative matters - a poor

assignment for his ambitions. It was above all risky in that it coincided with the

coup d'etat of 9 Thermidor - 27 July 1794. Buonaparte was imprisoned and had

to find inexhaustible excuses to avoid the worst.

Waiting for clarification of Napoleon's personal affairs, the Armee

d'Italie was champing at the bit. The General's worries were justified: Austria

was beginning to worry about the Italian front and had decided to reinforce it.

Not only this but Austria and Piedmont were collaborating, an arrangement that

until then had meant little more than verbal co-operation.

During this pause in circumstances, whilst discussing strategy, a suggestion made by Napoleon was accepted. This was that to hold the front it would be necessary that

Savona remained French. The Armee could then penetrate along the River Bormida in such a way as to divide the Piedmontese and the Austrians, thereby threatening to surround the latter.

Swift Campaign

A swift campaign which began on the 19 September was unexpectedly

highly successful. By the 24th, however, General Dumerbion considered that

his exhausted forces had to establish more secure positions by falling back a

considerable distance and setting up a new front line.

The oscillations in the fortune of Napoleon corresponded closely with

the operations on the Italian front. Involved in one of the periodic expulsions of

supernumerary officials and then overwhelmed by the flaring up of his pride,

only in the summer of 1795 did Napoleon return to the situation in Italy.

In fact, following the offensive taken by the Austrians on 29 June, General

Francois Christophe Kellerman, the new Commander of the Armee d'Italie,

had been driven back to Loano. The Bureau Topographique (more or less

the French General Staff) recalled Buonaparte because of his accurate

knowledge of the front.

He had just completed detailed reports on the subject when he found

himself yet again in an awkward situation on the 15 September. The difficulties

Buonaparte experienced in his career came to an end on 5 October -13

Vendemiare. This was the day he fired on those demonstrating in front of the

Tuilleries. It was also the day of the French, who were about to attain a

victory, advanced in Italy.

Italy First

Napoleon strongly advised the withdrawal of the troops from the Rhine

and the Pyrenees in favour of the Italian front, in order to recover the lost

positions and to finally divide the Austrian troops from those of Piedmont.

Buonaparte's point of view was accepted, but put into practice over too long a

period of time. Operations came to a standstill when serious conflicts arose

between the rapacious Austrian Commander in Chief, General Baron De Wins,

who was mainly involved in the plunder of Liguria, and his Piedmontese

equivalent Lieutenantgeneral Baron Michelangelo Alessandro Marchini Colli. Colli

was also supported by notables from Genoa, but even though the French were

also affected by the delays, these proved advantageous in their case.

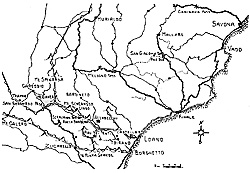

The lull in operations gave Kellerman the opportunity to reorganise his

own troops now positioned on the Borghetto line. Based on a mountainous

rampart, it started from Loano, and cut across the Maritime Alps to join in the

defence of the River Tanaro. The rugged terrain of the Western Ligurian

mountains heavily restricted the lines of communication whilst at the same time it proved effective as an excellent defence.

In addition the Piedmontese and Austrian troops, although well

drilled, were disoriented because their training did not include

mountain combat. It was too static and tied to defensive tactics.

The French were not affected by such limitations. Their demi-

brigades (the term "regiment" was abolished during the Revolution

because it had strong ties to traditional noble connections) had not

been so strictly drilled and therefore were not particularly

preoccupied by tactical principles. This was actually to their

advantage since it rendered them more flexible than other

detachments.

Courage

They were led on by the impetuous courage of their

young officers, who were full of idealism for the Republic.

The French armies travelled lightly with only their basic

needs and consequently were not encumbered with

excsssivs equipment and provisions. Admittedly, the men

themselves were in great need of shoes, the chronic

shortage of which characterised the campaigns of the Republican

period. This the lack of shoes would affect their fighting and

marching ability, not unlike the situation in the summer of

1795.

While the French were protected behind the line of the

Borghetto, their adversaries organised defensive positions

on the opposite bank. the Austrians positions ran from

Borghetto situated one kilometre west of Loano) to the Scravaion.

This is a pass cutting between the summit of the extremely sheer and

rugged mountains, in particular those extending down to the coast.

The Piedmont troops were lined up from Scravaion to Garessio,

following the Tanaro Valley on and on until the Tenda Pass.

the Piedmontese were the only ones to maintain pressure

on the French during the summer months.

These operations were for all practical purposes ineffective.

They were organised by General De Wins, who for his part avoided

exposing his command to the risk of an offensive. He was aware

that Prussia and Spain were possibly in the process of abandoning

the First Coalition, in which case the French could troops to the

Italian front, as suggested by Napoleon. The Austrian Commander

had no wish to provoke reinforcement of his adversary in the

Castelvecchio area by attacking the French on the 19 September.

Weak Attack

The attack by Austrian General Count D'Argenteau's army

corps was not a particularly strong one, but it resulted in failure as it

was directed against the strongest point of the French line. Known

as "Little Gibraltar", some soldiers were entrenched and some were

defended by a redoubt consisting of a high dry-stone wall. A

determined counterattack, however, allowed the French to

conclusively overturn the situation in their favour within a

few hours.

The new commander suggested that it was not possible to

carry out the plan that had been decided upon in August by

the Committee of Public Safety, based upon Napoleon's first

thoughts. He proposed an attack on the village of Ceva, intended

to separate the two coalition armies, followed by the recapture

of Vado, near the city of Savona. It was too ambitious an

objective for the Armee d'Italie which, although having reached

the strength of 33,000 men, was still outnumbered by the 30,000

Austrians and 12,000 Piedmontese.

Reshuffled Plan

The plan was therefore reshuffled by Scherer and

Massena, although preserving the intention of dividing the

Piedmontese from the Austrians. Now the main body of the

French army would attack the troops of Colli at Garessio and

Mount Spinarda, outflanking the Imperials in the Scravaion Pass

which acted as the hinge between the two armies. At the same

time the remainder of the Armee d'Italie would fix the Austrians

with a demonstration between the pass and the coast.

The movements behind the French lines did not escape the

Piedmontese commander. He took all the precautions he could, but

both his plans and also those of Scherer were nullified by the

abundant snowfall of the 15 November. The conditions of intense

cold, coupled with inadequate clothing and equipment, made it

impossible for the any units to remain on the harsh Ligurian

mountains.

The subsequent French attack began right from this area, in

accordance with a new plan devised by General Massena. The

manoeuvre was rather simple: fixing the flanks and breaking through

the centre. The key of success depended on the element of surprise,

the achievement of which was helped by the exchange of command

between De Wins, who was disliked by both the Austrians and the

Piedmontese, and General Baron Wallis, and also by the adverse

weather conditions.

Bad Weather

The bad weather in particular made it extremely likely

that the French units would withdraw to their billets and convinced

the elderly Austrian commanders that operations would be resumed

only in the following spring.

The Revolution had broken the rules traditionally followed by

the armies and inclement weather had now become a part of

the elements to be exploited in order to attain success.

During the night of the 22 November, the Austrians descended

from the summit and the ridge to make their way to the winter

quarters prepared at the bottom of the valley. Without disturbance

the 25,000 French soldiers completed their manoeuvres of approach

to the enemy lines, now sparsely guarded by depleted detachments.

The Austrian-Piedmontese armies consisted of more than

44,000 men scattered between Savona and the Col di Tenda Pass.

Although 19,000 Austrians were drawn up between the coast and

the Castle of Rocca Barbena, there were few defenders in the zone

where the French had attacked. In contrast, having been forewarned

by their informers, the Piedmontese, arranged between Rocca

Barbena and the valley of Tanaro, were ready for action, as

demonstrated by the facts of the day of the 23rd.

The French attacks began early. One, conducted by General

Miollis, was directed to the Valley of Tanaro, west of Garessio. The

other, led by Serurier, was aimed at the San Bernardo Pass to cut the

road to Rocca Barbena. By mid-morning the French found themselves

in great difficulty in both directions, whilst the Piedmontese

manoeuvred their units and cleverly exploited the hard terrain to

fire incessantly upon the enemy with their muskets and cannons.

The fact that Serurier had already begun to withdraw at

midday, without losing touch of the enemy, should not be taken as an

indication that this attack of the future Marshal was a weak one. The

task entrusted to him that day was carried out, namely to detain the

Piedmont army in its proper positions. This prevented it from assisting

the Imperial troops who were being subjected to greater pressures

by Massena.

In fact Massena, who was in charge of more than 13,000 men,

launched an attack before sunrise against the hinge between the

Piedmontese line and that of the Austrians. On the left, Division

General Amede Laharpe initiated two attacks. The one commanded

by General St.Hilaire against the Scravaion Pass was stopped by

Austrian and Piedmontese troops who were strongly

entrenched within the pass.

The other column was directed instead to the Piedmontese

positions in the upper valley of the Neva, a swift flowing mountain

stream, with the intention of distracting the attention of the defenders.

At the same time a strong contingent infiltrated, unseen, to outflank

the defence line which united the Lingo and brie Schenasso mountains.

Position Taken

This position was taken at about 0700. The French General

Pijion divided his forces instructing one column to outflank the

Piedmontese who were engaged in a skirmish with the

diversionary attack ordered b, Massena. The other column,

meanwhile, converged on the Scravaion Pass reaching the rear of

the Coalition units facing St.Hilaire.

At 10.00 the main part of the Piedmontese was driven back

towards the North, the slopes of Mount Cianea. They were now

cut-off from the troops of Austrian General D'Argenteau, in spite of

the vigorous counter-attack led later by Baron Colli, who in the

meantime succeeded in reorganising his own forces.

On the right of Massena, the fighting had a less

favourable beginning. In fact at about 6.00, D'Argenteau,

becoming aware of the movements the French troops led by

General Charlet, immediately reinforced his own lines between

the Saddle of the Alzabecchi and Rocca Barbena. The

Austrians here demonstrated the quality of their own training

and the orderly and precise fire of their line began to mow

down the French columns.

When General Charlet was among the victims the

revolutionary troops hesitated but, with immediately Massena

took command of Charlet's troops and also commisted the

reserve units of General Bizanet Desprte the Imperial troops

solidly holding Rocca Barbena, they could not resist the blow

when they were attacked by Massena and consequently began to withdraw.

In defence, the Austrians' commander of the sector, General

Liptay, reorganised his troops in the valley near the centre of

the village of Bardineto. Immediately, however, his

positions appeared threatened by the convergence of the

French vanguards. Laharpe's, led by General Pijion,

descended from the Scravaion Pass and Massena's, under

General Jean-Baptiste Cervoni, came from the Saddle of the

Alzabecchi.

More Loano

In the summer of 1995, men dressed in

threadbare uniforms of the French Revolutionary period had taken the Doria

Palace by storm. Then, at bayonet point, the Austrian defenders of the 16th

century town hall of Loano were hereded into the town square along with a good

number of municipal employees, and for good measure, the mayor.

In the summer of 1995, men dressed in

threadbare uniforms of the French Revolutionary period had taken the Doria

Palace by storm. Then, at bayonet point, the Austrian defenders of the 16th

century town hall of Loano were hereded into the town square along with a good

number of municipal employees, and for good measure, the mayor.

French reinforcements were in fact beginning to arrive.

6,000 men came from the Rhine and 10,000 from Spain,

but the final addition to the Armee d'Italie was only 12,000

men - the difference being caused by strategic consumption.

With them on 21 September arrived General Barthelemy Scherer

who replaced Kellerman, transferred to Armee des Alpes.

French reinforcements were in fact beginning to arrive.

6,000 men came from the Rhine and 10,000 from Spain,

but the final addition to the Armee d'Italie was only 12,000

men - the difference being caused by strategic consumption.

With them on 21 September arrived General Barthelemy Scherer

who replaced Kellerman, transferred to Armee des Alpes.

The French soldiers were shabbily dressed, but their Austrian

colleagues suffered in equal measure since their clothes and

equipment were worn-out by the long campaign too. The units,

therefore, began to disperse and withdraw to the zone behind the

front line. The French thought it would be easy to seize this

opportunity to advance but, approaching the Austrian quarters, the

resistance stiffened. General Charlet succeeded in occupying the

important positions of Pian dei Prati abandoned by the Imperial troops.

The French soldiers were shabbily dressed, but their Austrian

colleagues suffered in equal measure since their clothes and

equipment were worn-out by the long campaign too. The units,

therefore, began to disperse and withdraw to the zone behind the

front line. The French thought it would be easy to seize this

opportunity to advance but, approaching the Austrian quarters, the

resistance stiffened. General Charlet succeeded in occupying the

important positions of Pian dei Prati abandoned by the Imperial troops.

For the whole day their sector held off the right flank of the French, commanded by General Philibert Serurier, which concluded with both adversaries still occupying their original positions.

For the whole day their sector held off the right flank of the French, commanded by General Philibert Serurier, which concluded with both adversaries still occupying their original positions.

Battle of Loano (I)

Battle of Loano (II)

Loano Order of Battle

Re-enactment Photos (extremely slow: 743K)

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 21 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com